In a retreat from its Cariou decision, the Second Circuit finds that Andy Warhol’s use of a Lynn Goldsmith photo of the pop icon Prince isn’t transformative. But lots of questions remain.

UPDATE—March 28, 2022. The U.S. Supreme Court granted cert. in the Warhol case today, agreeing to review the Second Circuit’s fair use opinion. The last time the Court considered whether a creative work constituted a “transformative” fair use under the Copyright Act was in 1994’s unanimous “Oh, Pretty Woman” decision, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. Of the Court members who will decide the Warhol case, only Justice Thomas was on the bench back then. Check out my full breakdown here.

From Marilyn Monroe to Jackie Kennedy to Michael Jackson, Andy Warhol spent a good portion of his artistic career creating silkscreen portraits of iconic celebrities, putting his work squarely at the intersection of culture and commerce. Last week, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, presiding as the traffic cop over that intersection, ruled that Warhol’s “Prince Series” did not make fair use of photographs taken by Lynn Goldsmith, a famed music and celebrity photographer in her own right.

While the end result in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (read here) will be hailed by photographers and other similarly-situated content creators, it also ratchets up the confusion meter for anyone sitting on the sidelines trying to make sense of the Second Circuit’s fair use landscape. That’s because in finding that Warhol’s “Prince Series” wasn’t fair use, the court had to engage in a 56 page act of contortion to explain the differences between Warhol’s piece and that of another modern artist, Richard Prince, which received much more favorable fair use treatment from the court in 2013. Consider it the tale of Two Princes. And much like the Spin Doctors’ song of the same name, it may sound ok at first, but won’t be particularly satisfying for anyone in the long run.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for The Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith

The Facts

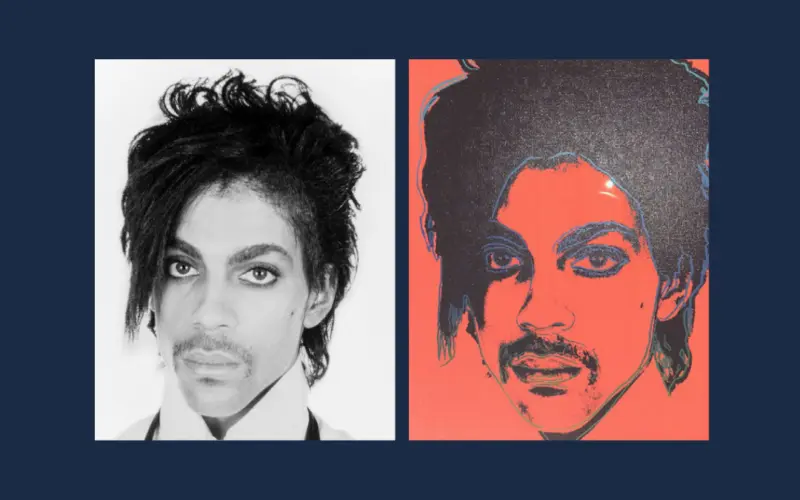

Before we get there, let’s start with the facts of the case, which are are pretty straightforward. In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith took a number of photos of the musician Prince at her studio, including the image below:

While Goldsmith never published her photo, in 1984 she granted Vanity Fair’s request to license the image for use as an “artist reference.” Vanity Fair then commissioned Warhol to use Goldsmith’s photo to create an artistic rendering of Prince for its November 1984 issue. Warhol’s illustration, together with an attribution to Goldsmith, was published in an accompanying article about Prince:

Warhol’s creation of the Prince image featured in Vanity Fair was pursuant, at least indirectly, to a license from Goldsmith. However, without the photographer’s knowledge, Warhol created 15 additional works based on her photo, which were collectively known as Warhol’s “Prince Series.” The Prince Series includes 14 silkscreen prints and two pencil illustrations, some of which are depicted below:

On April 22, 2016, the day after Prince died, Condé Nast, Vanity Fair’s parent company, contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF), which by this point had succeeded to the rights previously held by Andy Warhol following the artist’s death in 1987. Upon learning that AWF had additional images from the Prince Series, Condé Nast ultimately licensed the following image for a tribute magazine published in May 2016:

This time around, Goldsmith wasn’t given any credit or attribution for the image, which was instead attributed solely to AWF.

It was at this point that Goldsmith first became aware of the Prince Series. She reached out to AWF to inform it of the perceived infringement of her copyright. AWF thereafter sued Goldsmith, seeking a declaratory judgment of non-infringement. Following AWF’s lawsuit, Goldsmith filed a counterclaim for copyright infringement.

The District Court’s Ruling

In 2019, Southern District of New York Judge John G. Koeltl granted summary judgment for AWF on its fair use claim. Among its key findings, the court concluded that the Prince Series was “transformative” because, while Goldsmith’s photo portrays Prince as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” the Prince Series portrays the musician as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Comparing the works side-by-side, the district court concluded, it was apparent that a reasonable observer would perceive that Warhol’s work has a “different character, a new expression, and employs new aesthetics with [distinct] creative and communicative results” when compared to the Goldsmith original.

The court’s determination that Warhol’s work was transformative served as a launching pad for its finding that all of the other fair use factors weighed in AWF’s favor as well. Notwithstanding that Goldsmith’s photograph was unpublished, that Warhol had arguably used the heart of her work, and that Goldsmith had already demonstrated a market for her work (indeed, to the very licensee that commissioned Warhol’s version), the court found in favor of AWF as a matter of law. Goldsmith appealed.

The Second Circuit’s Decision

In reversing the lower court’s opinion, the Second Circuit faulted the court for ruling that the Warhol work was transformative as a matter of law, suggesting that the lower court had interpreted the 2013 opinion in Cariou v. Prince too literally. Frankly, the appellate court went a bit far in throwing Judge Koeltl under the bus.

That’s because, whatever you think of the lower court’s decision in Warhol, the outcome was practically preordained by Prince v. Cariou. (Again—and apologies for any confusion—that case involved appropriation artist Richard Prince the artist, not Prince the musician.) Cariou represents, by the Second Circuit’s own admission, the “high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works,” with the court holding the vast majority of pieces used in Richard Prince’s “Canal Zone” series constituted fair use as a matter of law. The court couldn’t determine whether five additional Prince works were protected by fair use, and remanded those to the district court for further proceedings. (The case settled prior to any additional fair use rulings in the case.)

The Second Circuit panel in Goldsmith acknowledged that Cariou has been the subject of criticism. Some of it has been targeted at a perceived elitist approach to fair use in which well known (and expensive) modern art is given an unfair advantage in the fair use inquiry. Criticism has also been levied at the very idea of courts acting as pseudo-art critics, with the Cariou panel seeming to go out of its way to ascribe a meaning and message to Cariou’s work that even the artist himself hadn’t advanced. (The Second Circuit distinguished between Cariou’s “serene and deliberately composed” originals and Richard Prince’s versions, which the Court characterized as “hectic and provocative”; for his part, Prince himself maintained that his only intent was “to make great art that makes people feel good.”)

Away From Cariou and Toward Confusion?

While the Goldsmith panel recognized that it was bound by Cariou, it’s hard not to see the new opinion as a repudiation of the earlier case. At the very least, it seems to signal that the fair use pendulum is once again shifting (especially if you pair the decision with last December’s Ninth Circuit opinion in Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix).

The clear import of Goldsmith is that courts should not automatically recognize any alteration to an original work as transformative—regardless of who’s doing the altering. The problem, of course, is that the court really hasn’t offered any guidance on what is transformative. Why was Richard Prince’s composition, color palette and media deemed “fundamentally different and new” compared to the original work, but not Warhol’s? Why was the Second Circuit able to decide that Warhol’s image wasn’t protected by fair use as a matter of law when it was unable to do so for images in Cariou that are arguably less transformative than Warhol’s? Who knows.

This confusion is likely to be exacerbated by some puzzling statements within the Goldsmith opinion itself, most notably the Court’s suggestion that “derivative works” and “works subject to fair use protection” are somehow mutually exclusive. The court pronounced that “there exists an entire class of secondary works that add ‘new expression, meaning, or message’ to their source material but are nonetheless excluded from the scope of fair use: derivative works.”

I’ve read this passage a number of times, and to be honest, I’m still not entirely sure what the court is trying to imply. The court certainly can’t be suggesting that all derivative works are excluded from the scope of fair use. After all, the Copyright Act makes an owner’s exclusive rights (including the right to prepare derivative works) expressly subject to Section 107’s fair use right.

Simply labeling a work as “derivative” says nothing about whether or not that particular use is fair. In other words, if a work qualifies as a fair use, the fact that it would constitute an unlawful derivative work in the absence of the fair use doctrine is irrelevant. Indeed, the Second Circuit itself recognized this basic principle not too long ago in the Authors Guild v. HathiTrust case, when it wrote: “there are important limits to an author’s rights to control original and derivative works. One such limit is the doctrine of ‘fair use,’ which allows the public to draw upon copyrighted materials without the permission of the copyright holder in certain circumstances.”

Where Now?

That brings us back to Goldsmith and what I believe should be one of the fundamental purposes of court opinions: to help the public (and potential future litigants) understand the court’s view of the law and to reasonably predict how a future case may be decided on similar facts. Reasonable minds can differ as to whether a retrenchment from Cariou is a good thing or not. I personally think that a pendulum shift was in order—but I’m more concerned about how district court judges, lawyers and copyright litigants are expected to make conclusions about what the court is likely to do in future cases. So long as an inquiry into whether or not a work is transformative continues to drive the entire fair use narrative, it’s hard to know where the court will draw the line. Consider this: in Cariou, ComicMix, and now Goldsmith, appellate panels have all reversed the district court decisions below—decisions all prepared by well-meaning district court judges who thought they were following the law.

As an aside, the pendulum shift that may be most overdue at this point is to remind courts that the concept of transformative use is not the end-all-be-all when it comes to the overall fair use inquiry. In particular, the fourth fair use factor (the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work) has taken a back seat in recent years, but may be due for a comeback. Goldsmith strikes me as an example of a case in which a court could find that the fourth fair use factor weighs against fair use, even if Warhol’s work is deemed to be transformative under Cariou. This is especially true when one considers that Vanity Fair obtained a license from Goldsmith in order for Warhol to create the Prince Series in the first place, only for the publisher to later license (and credit) Warhol’s version to the exclusion of Goldsmith.

So what do you all think? Now that Cariou and Goldsmith are both on the books, where does the Second Circuit go from here with respect to fair use? Let me know in the comments below or on your social media platform of choice @copyrightlately.

4 comments

My hope is that this case is taken up en banc at the Second Circuit, or even granted cert. Scholars, practitioners, and artists all have strong opinions about the Cariou opinion, but it is at least workable in practice. I agree with this author’s assessment: This opinion brings confusion and chaos to the fair use inquiry, and it will likely lead to cases with similar facts all being decided differently as district courts try to operationalize Goldsmith’s “I know it when I see it” standard for transformative. The court’s offhand declaration that works that draw from many sources are more likely to be transformative than works that draw from one or a few sources may end up creating perverse incentives for artists. Though unlikely, there is always a chance that the pending SCOUTS decision in Oracle v. Google will add some clarity to the transformative use inquiry (if they choose not to resolve the case on more narrow grounds).

En banc review is exceeding rare (practically non-existent) in the Second Circuit. It’s been almost 30 years since the Supreme Court took up a fair use case. Will this be the one?

Thanks Aaron.

Section 107 expressly says Nimmer’s 4 fair use factors are non-exclusive (“…the factors to be considered shall include..”) but not a single decision since 1979 has dared to venture beyond a robotic recitation of ‘..the 4 factors,’ with “transformation” (a mutant arm of the first factor, character and nature of the use) acting as a catch-all safe harbor for fuzzy-thinking judges. But see, Seltzer v. Green Day. !

While it doesn’t merit a separate discussion in most, if any cases, I think that “Does the judge think you’re a jerk” may be the unspoken 5th factor. That often drives analysis of the other four, because judges are only human.