Copyright termination and bankruptcy law collide as members of 2 Live Crew attempt to recapture rights in the group’s most notorious albums.

In the late 80s and early 90s, hip-hop was controversial, and no group generated more controversy than 2 Live Crew. Granted, this was at a time when even thinly-veiled sexual innuendos by mainstream pop singers like Cyndi Lauper and Sheena Easton prompted congressional hearings. But 2 Live Crew’s lyrics were anything but subtle, and landmark legal actions soon followed.

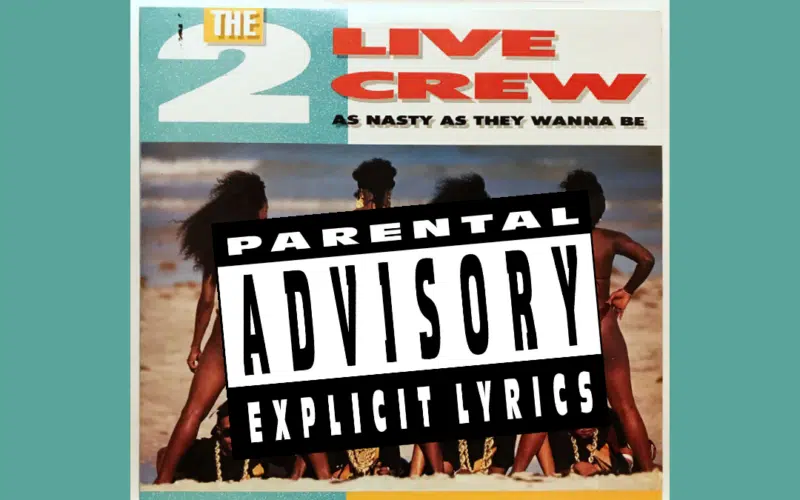

“Nasty” and Obscene?

The group’s 1989 release “As Nasty As They Wanna Be” was the first sound recording in U.S. history to be declared legally obscene by a federal judge. That ruling was later reversed by the Eleventh Circuit, but not before a Florida record store owner was arrested for selling 2 Live Crew’s album and members of the group were put on trial for performing songs from it.

Their next record, the aptly-titled “Banned In The U.S.A.,” was the first to carry the RIAA’s now-ubiquitous “Parental Advisory: Explicit Content” sticker, following pressure from the Parents Music Resource Center and its founder Tipper Gore. (If you thought the Bret Kavanaugh hearings were riveting, picture a C-SPAN camera trained on a 19-inch tube TV as a room full of geriatric senators are forced to sit through “Hot For Teacher” and “We’re Not Gonna Take It” on live television.)

“Clean,” “Pretty” and Fair?

In 1994, allegations of copyright infringement, not obscenity, landed 2 Live Crew at the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. Ironically, the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case involved one of the group’s tamer songs, a juvenile take on Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” from the heavily sanitized “As Clean As They Wanna Be.” The Court held the Sixth Circuit erred in concluding that the commercial purpose of 2 Live Crew’s parody version rendered it presumptively unfair. Campbell also introduced the concept of “transformative use” into the Supreme Court’s fair use lexicon—a topic the Court will soon revisit when it decides the Andy Warhol case later this term.

Lil’ Joe Makes a Deal

By 1995, more mundane legal disputes over unpaid royalties had driven 2 Live Crew’s leader, Luther “Luke” Campbell, and his record label, Luke Records, into bankruptcy court. Among their creditors was Joseph (“Lil’ Joe”) Weinberger, a tax lawyer who served as Luke Records’ CFO and in-house counsel. (Campbell’s label originally went by “Skyywalker Records” before being forced to change its name after yet another lawsuit, this time by some guy named Lucas.)

Weinberger bought the rights to 2 Live Crew’s master recordings out of bankruptcy for $800,000 and formed his own label, Lil’ Joe Records, to distribute them. In later years, two of the three remaining members of 2 Live Crew, Christopher Wong Won (aka Fresh Kid Ice) and Mark Ross (aka Brother Marquis), also cut deals with Weinberger. Lil’ Joe Records has been collecting royalties on 2 Live Crew’s music ever since.

As Litigious As They Wanna Be

Now, fast-forward to late 2020, when Campbell saw a chance to finally turn the tables on Lil’ Joe. The 35th anniversary of 2 Live Crew’s first album was soon approaching, and with it the opportunity for the group’s members to terminate their original recording agreement with Skyywalker Records. Joined by Ross and the heirs of Wong Won, who died in 2017, Campbell served a Notice of Termination (read here) announcing that the members of 2 Live Crew would recapture the copyrights in their albums beginning in November 2022. The group is relying on Copyright Act section 203(a), which gives artists the ability to terminate rights under previous copyright assignments after 35 years.

But Lil’ Joe wasn’t giving up without a fight. After receiving the termination notice, Weinberger and his label decided that the best defense was a good offense, and Lil’ Joe preemptively filed a lawsuit in the Southern District of Florida against Campbell, Ross, and all the Wong Won children (read complaint here). The company seeks a judicial declaration that the defendants have no termination rights to exercise and that their notice is invalid as a matter of law. The defendants responding by filing a counterclaim for a declaration that they’ll become the copyright owners in the 2 Live Crew albums at issue on the dates set forth in their termination notice.

In September 2022, Lil’ Joe filed a summary judgment motion in the case (read here). Not to be outdone, last week the defendants filed their own motion for summary judgment (here), setting the stage for 2 Live Crew’s latest entry into law school textbooks.

Copyright Termination x Bankruptcy Law

I’ve written before about copyright termination in the context of both family law and wills and trusts, but the latest lawsuit between Lil’ Joe Records and 2 Live Crew is the first case I’m aware of that squarely raises the interplay between copyright termination and bankruptcy law. Before diving in, let me fill in a few more details.

Just a Tiny Bit of Bankruptcy Background

Filing a petition for bankruptcy creates an entity known as a bankruptcy estate, which succeeds to all of a debtor’s interests. In 1995, Luke Records was actually forced into an involuntary bankruptcy by the company’s creditors. Luther Campbell then filed a voluntary petition, and both bankruptcies were ultimately administered as chapter 11 reorganization cases.

Unlike chapter 7 liquidation proceedings, a case under chapter 11 is designed to allow a business to continue operating while the owner and its creditors reorganize the company’s debts. The debtor typically remains “in possession” and may continue to operate its business. During the course of the bankruptcy proceeding, a plan of reorganization is proposed, and affected creditors vote on the plan, after which the court will be asked to confirm it.

Ok, That’s Enough Bankruptcy Background. What’s Going On Here?

Here, the debtors-in-possession (Campbell and Luke Records) and the estates’ Unsecured Creditors’ Committee (representing the creditors who were owed money) created a joint plan to pay the bankruptcy estates’ debts.

Under the reorganization plan approved by the bankruptcy court in 1996, Campbell and Luke Records transferred certain specified assets to Lil’ Joe Records and Weinberger “free and clear of any and all liens, claims, encumbrances, charges, setoffs or recoupments of any kind.” Among those assets were all of the copyrights and publishing interests held by Campbell and Luke Records in the 2 Live Crew sound recordings and compositions.

By 2000, Mark Ross had also filed bankruptcy, with Lil’ Joe claiming that Ross owed him money. As part of a settlement agreement, Ross acknowledged, among other things, that he had no rights (master or publishing) in any of the 2 Live Crew records. Then, in 2002, Lil’ Joe sued Wong Won, who settled by agreeing to confirm that Lil’ Joe owned all of the 2 Live Crew copyrights and releasing “any claims whatsoever” in connection with those works.

Now, 20+ years later, the members of 2 Live Crew are looking to extricate themselves from those previous not-very-good deals. The two main issues raised by the new litigation are (1) whether the 2 Live Crew members’ prior bankruptcy filings and copyright transfers to Lil’ Joe resulted in the members giving up their termination rights; and (2) if not, whether the 2 Live Crew sound recordings were created as works made for hire, which would mean they were never eligible for copyright termination in the first place.

Are Termination Rights an Asset of the Bankruptcy Estate?

In its motion for summary judgment, Lil’ Joe Records makes the novel argument that any statutory termination rights held by Luther Campbell and Mark Ross became assets of their respective bankruptcy estates. The company cites Bankruptcy Code section 541, which provides that a bankruptcy estate is comprised of “all legal or equitable interests of the debtor in property as of the commencement of the case.”

Lil’ Joe doesn’t cite any legal support for the proposition that section 203(a) copyright termination rights are assets of a bankruptcy estate, and the company’s argument isn’t particularly strong. Termination rights don’t vest until a termination notice is served, and don’t actually accrue until the effective date of termination. At the time Campbell and Ross filed bankruptcy, they didn’t own any termination rights—those rights wouldn’t vest for over 20 years.

More importantly, there’s no indication that Congress intended for the Bankruptcy Code to trump the Copyright Act and prevent the termination of a copyright transfer that’s otherwise eligible. Courts have often noted that termination rights are “inalienable” and “may be effected notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.”

Lil’ Joe’s argument also presumes that the copyright termination right is a contingent property interest that’s capable of being transferred. But Congress has explicitly limited the classes of individuals who are entitled to effectuate termination (the artist and the artist’s widow(er) and children). Entities like record labels aren’t eligible.

Were the 2 Live Crew Sound Recordings Works Made For Hire?

Assuming the district court finds that the 2 Live Crew members’ bankruptcies didn’t relinquish their right to serve copyright termination notices, the second main issue in the case is whether the notices themselves are valid. To decide that question, the court will first need to identify the operative grant in the 2 Live Crew sound recordings. Once again, there’s a disagreement.

Lil’ Joe relies on a 1991 recording agreement which explicitly stated that the members’ contributions to 2 Live Crew’s sound recordings were owned by Luke Records as an employer for hire. But that contract was executed after the creation of the albums at issue in the members’ termination notice, and appears to contemplate future recordings that aren’t at issue.

Meanwhile, the members of 2 Live Crew contend that between 1986 and 1990 they operated under an oral agreement, which was later memorialized in an undated recording agreement executed “in or around 1990.” That agreement had a stated effective date of January 1, 1987. It provided that Skyywalker Records (as predecessor to Luke Records) would own all of the 2 Live Crew master recordings, and that the label would in turn pay royalties to the members based on records sold.

It isn’t clear from the face of the 1990 agreement whether the members of 2 Live Crew intended to assign their copyrights to Skyywalker Records or for Skyywalker to own them from inception as employers of the group. Because the recordings were created when the 1976 Copyright Act was in effect, the court will likely apply the common law agency factors set forth in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid to determine whether the members were employees of their record label.

Both sides are seeking summary judgment on the work for hire issue, but there may well be enough conflicting evidence to require a trial. On one hand, the 1990 recording agreement gave Skyywalker Records the right to designate times and places for recording sessions, the right to require the members of 2 Live Crew to re-record material until a sound recording acceptable to the label was obtained, and the sole authority to approve the results of the group’s recording sessions. The label was also responsible for all recording costs and fees, including payroll taxes.

But the members of 2 Live Crew have all executed sworn declarations in which they deny that they were ever employees of Skyywalker Records. They claim that the group made its own artistic choices and had the freedom to set its own schedule, that the record label had no right to assign additional projects, and that the label didn’t provide the members with any health insurance, paid vacation time or other benefits. All of these factors weigh against an employer-for-hire relationship.

No hearing date has yet been set on the parties’ dueling motions for summary judgment, but I’ll be sure to post updates as they develop. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts on 2 Live Crew’s latest legal battle. You can leave a comment below, or use @copyrightlately on whatever social media platform you’re using nowadays.

3 comments

2 live crew must get back music catalog

just sale them back their catalog & close the case out lil joe weinberger is a crook

correction It was Mark Ross and his manager who initiated the termination case and ask Campbell and Chinaman’s heirs to join. It was Mark who gave the permission to his manager to begin the facilitation of the case and vet and attorney that was capable of representing the members on a contingency fee.