Copyright professor Jack Lerner and his law students read every fair use case from the past two years so you don’t have to. Here are some of the highlights.

I had an opportunity to catch up this week with Professor Jack Lerner, director of the Intellectual Property, Arts, & Tech Clinic at the UC Irvine School of Law. In honor of February’s fair use week, Professor Lerner and his students embarked upon an ambitious project: review and analyze every fair use opinion issued in the United States over the past two years. In all, 72 fair use cases were decided during that time period, all of which have been compiled and summarized in the IPAT Clinic’s full report.

I asked Professor Lerner about the highlights from the study, along with some of the conclusions he’s reached about the current fair use landscape.

Aaron Moss: What was the most surprising thing you found based on your analysis of all these cases?

Jack Lerner: The sheer number of photography cases really shocked us. Of the 72 cases over the past two years which resulted in opinions made available on Lexis or Westlaw, 37 of them were about photographs.

AM: When I think about copyright cases involving photos, it’s hard for me not to also think about Richard Liebowitz and other attorneys who have constructed an entire business model out of these lawsuits. Do you think a court is more likely to find fair use in cases in which the plaintiff (or the plaintiff’s lawyer) appears to be using litigation as a business or income-generating tool?

JL: I think this does matter to a degree—but perhaps not as much as it should. When a for-profit business uses someone’s photograph for a promotional brochure or on a billboard, they should get a license. But the problem is that for these “frequent-filer” plaintiffs, that’s not really their market. Rather, their “market” is exorbitant payouts based on ruthless exploitation of inequities in the copyright system. As Paul Levy from Public Citizen puts it, the demand amounts often “appear…to have been carefully calculated to be less than targets would likely spend on competent copyright lawyers to advise them on their likely liability or to defend against the threatened litigation.” This should heavily influence the “market harm” prong in fair use, and we have seen that in some cases; and there is no reason courts cannot take other equities into account when doing a fair use analysis. Overall, however, the courts have not taken this approach and instead stuck to the four statutory factors. In fact, they have been rather solicitous of plaintiffs’ claims in the fair use analysis.

AM: What were some of the more interesting fair use decisions you encountered?

JL: Reading all these cases reminded me of how vast America is in its absurdity, ambition, humor—and sometimes tragedy. There was Swartzwald v. Oath, Inc., the case in which Huffpost used a paparazzi shot of Jon Hamm to humorous effect in a post titled “25 Things You Wish You Hadn’t Learned in 2013 and Must Forget in 2014,” and then there was Basset v. Jensen, the case of a woman who rented out her Martha’s Vineyard home only to have it be used in a porn shoot.

In terms of fair use jurisprudence, Chapman v. Maraj, about the music industry practice of experimenting with a song before seeking a license, was really interesting—and important. Nicki Minaj recorded a song that used the chorus of Tracy Chapman’s “Baby Can I Hold You,” and the court granted summary judgment for Minaj as to the creation of a derivative work. The court got it right: the point of copyright is to incentivize the creation of new works, and that was what Minaj was doing here. Minaj made no attempt to commercially exploit Chapman’s song, and there was no evidence that Minaj’s private experimentation with that work could have harmed the market for Chapman’s work. This type of experimentation is also common practice, by the way, in the film business.

This case is also interesting because it reaffirms the argument Michael Madison made in his influential 2003 article “A Pattern-Oriented Approach to Fair Use.” Madison argued that fair use serves to validate important societal values, and this explains the “often-difficult conceptual gap between fair use claims asserted by individual defendants and the social implications of accepting or rejecting those claims.” Madison’s paper was the theoretical basis for the game-changing codes of fair use best practices, and it is still valuable today as a way to look at fair use.

AM: Are there any courts that appear to be more receptive to fair use than others?

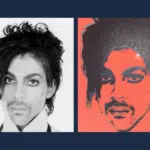

JL: One could argue that as a jurisdiction gets more experience with fair use, the analysis gets more sophisticated. The Second Circuit has been a hotbed of fair use cases lately; that circuit is responsible for 33% of all fair use cases since the beginning of 2019, and 25% of cases overall are from the Southern District of New York alone (that’s Manhattan, NY). The district court judges there have some very nuanced opinions to guide them, particularly Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley and Cariou v. Prince. I think by and large the judges of that district have had a pretty good approach.

AM: Any case that you thought was particularly wrongly decided?

JL: I was disappointed by the decision in Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, which held that a “mash-up” of Dr. Seuss’s “Oh, The Places You’ll Go!” and the Star Trek universe was not fair use. I would have liked to see a more thoughtful discussion of the meaning mash-ups often have in the digital environment. The court helpfully confirmed that “mash-ups” can indeed be fair use, but it missed an opportunity to make more clear that the act of juxtaposing two very different forms together can be deeply subversive and communicate a very strong critique of the works used. More fundamentally, however, transformative use does not require direct critique of the original work; if you are using one work to contextualize, explain, or reconsider another’s meaning, that is transformative use—and when it comes to culturally resonant works like “Oh, The Places You’ll Go!”, that’s even more likely to be the case.

The decision in Dlugolecki v. Poppel was also problematic. There, ABC used photos of Meghan Markle from her middle and high school yearbooks in news stories; though the court thought the use was somewhat transformative, it ultimately denied defendant’s motion for summary judgment on fair use. The court should have given much more weight to the historical and biographical nature of the photos in question, and to the huge difference between a journalistic photo and a yearbook photo taken many years earlier. Yearbook photos constitute an important documentary and historical record and courts should give news reporters, scholars, and others wide latitude to use them for such purposes. Fortunately, the court’s holding is quite limited; the case merely held that the defendant’s fair use argument could not be decided as a matter of law on summary judgment.

AM: If bloggers or other internet publishers want to use a photo without obtaining a license, what are some of the “best practices” based on the case results?

JL: At the UC Irvine IPAT Clinic, we tell our clients to be very careful about posting photos online. Repeat after me: just because it’s online does not mean you can use it! Instead, make sure you are doing one of the following:

- Get a photo from a free service like Pixabay, Unsplash, or Pexels. These can be used freely and without attribution.

- Buy a license from Getty, Shutterstock, or a similar company.

- Use photos published with an “open license” such as Creative Commons licenses. There are millions out there; Flickr and Google both allow you to search by usage rights. However, if you do this, you must provide proper attribution, which the license will spell out. We tell our clients to: state the name of the rightsholder or user; link back to the original photo; and link to the Creative Commons license in question. Sadly, Creative Commons licenses are tricky because at least one unscrupulous rightsholder has a business model of posting his photos on Wikimedia Commons and then lying in wait for people to post his photos without attribution, thinking they were free to use.

- Use photos to which you own the rights. For example, you took the picture or got a license from someone.

- Use public domain photos—anything publicly distributed before 1926 or created by the US government.

- Make fair use of the photo!

AM: Are there any big picture take-aways that you’d draw from your study?

JL: I think fair use remains safe and reliable when you make it in an informed way and with intention. But I also think the courts need to resist a mechanical conception of transformative use that relies on direct critique of the original work. There are many ways to add “something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message”; direct critique is not always necessary to do that.

AM: What are the next steps for your project?

JL: Our next step is to review pre-2019 cases to see whether there has indeed been an uptick—maybe there have been this many fair use cases all along?—and if so, when it started. We also plan to update this repository periodically. Also, there have recently been some great empirical analyses of fair use, and we’ll be taking a look at how this project informs that work, and vice versa.

I want to give a big thank you to Professor Lerner for taking the time to sit down with Copyright Lately! Here are the links to the IPAT Clinic’s report, Fair Use Jurisprudence 2019-2021: A Comprehensive Review: