The Ninth Circuit’s fair use ruling is an early Christmas present for copyright owners and a lump of coal for creators of unauthorized mash-ups that don’t ridicule the original works.

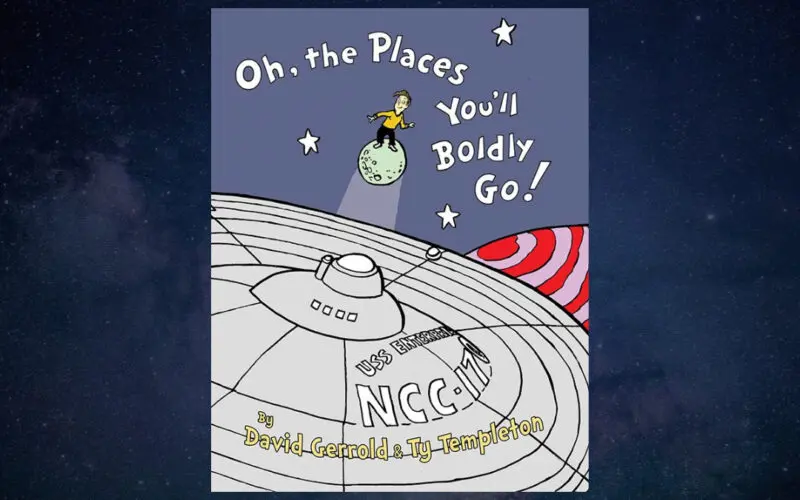

In an anxiously-awaited decision, the Ninth Circuit today forcefully held in Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. ComicMix, LLC (read here) that the Dr. Seuss/Star Trek mash-up “Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go!” isn’t a parody, isn’t transformative and isn’t a fair use protected by the U.S. Copyright Act. The case reverses a March 2019 ruling out of the Southern District of California. In that case, Judge Janis Sammartino found that defendant ComicMix’s crowdfunded book qualified as a transformative use (though not a parody) of the 1990 Dr. Seuss graduation present staple “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!”

Following the district court’s decision, plaintiff Dr. Seuss Enterprises appealed. A number of amicus parties supporting the interests of copyright owners, including the Motion Picture Association of America and the Copyright Alliance, expressed concern that an affirmance would give a green light to a wide variety of unauthorized derivative works. As Dr. Seuss Enterprises framed the issue, recognizing a “mash-up exception” would excuse infringement so long as a defendant used material from two authors instead of just one.

An equally-impressive roster of amicus parties lined up on the side of ComicMix, including Electronic Frontier Foundation and Public Knowledge. They argued against an overly-restrictive application of fair use that they said would stifle creative expression.

In a virtual oral argument held in April 2020, the Ninth Circuit panel appeared skeptical of the district court’s ruling. Judge Margaret McKeown, who authored today’s majority opinion, at one point suggested that the definition of transformative use advocated by ComicMix “would seem to sink the whole notion of copyright protection and almost everything would be fair.”

Even though the Ninth Circuit’s decision wasn’t entirely unexpected in light of these comments, I found the seeming ease with which the court dispensed its ruling a bit surprising. Frankly, it wasn’t even close.

But before we go there, let’s take a quick step back.

“The Cat NOT in the Hat” and Beyond

The dispute over “Boldly” hasn’t been Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ first rodeo as far as unauthorized Seuss works are concerned. In 1997’s Dr. Seuss Enterprises, LP v. Penguin Books, the Ninth Circuit held that a retelling of the O.J. Simpson murder trial in the style of Dr. Seuss was not a parody and didn’t constitute a fair use of “The Cat in the Hat.” Instead of commenting on the original, “The Cat NOT in the Hat!” simply used the Seuss work as a “vehicle” to poke fun at an unrelated target.

In the 23 years since Penguin Books was decided, courts’ notions of the types of uses that can qualify as transformative—and therefore fair use—have been refined and expanded. Within the Ninth Circuit itself, the Court held in Seltzer v. Green Day that the defendants’ use of the plaintiff’s drawing of a screaming, contorted face in their music video was transformative even though the band’s video didn’t contain any commentary on the original work. In the Second Circuit, the court in Cariou v. Prince held that an artist’s use of the defendant’s photographs to create collages was transformative where the photos were used as “raw material” for a different purpose than the original.

Fair use cases certainly haven’t all been decided in favor of defendants. However, the importance of Penguin Books did seem to recede in importance over the years, and parody hasn’t been essential to a finding of transformative use. Perhaps to underscore the point, the district court’s decision in ComicMix, rather surprisingly, did not even mention “The Cat NOT in the Hat” or the Ninth Circuit’s Penguin Books decision in finding that ComicMix made fair use of “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!”

Today, the cat came back.

The Ninth Circuit’s Opinion

I’ve written a bit already about the four factor test employed by courts in fair use cases. Most courts try to march through the factors rather methodically, but the extent to which a work is found to be transformative on the first factor usually colors the court’s view of the remaining factors.

The Purpose and Character of the Use

The ComicMix court divided its first-factor inquiry into a discussion of whether “Boldly” was a parody, followed by a discussion of whether it was otherwise transformative.

Parody

The court devoted most of its first factor treatment to an evaluation of the parodic nature of the defendant’s work. In doing so, the court largely adopted the same reasoning it employed in Penguin Books, finding that while “Boldly” may have broadly mimicked Dr. Seuss’ characteristic style, it didn’t hold that style up to ridicule or critique. Instead, the court found, ComicMix simply used the expressive elements of the Seuss works to “get attention or maybe even to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh.”

While some courts have moved away from rigid distinctions between “parody” (which has historically been protected) from “satire” (which hasn’t), those distinctions still appear to inform the Ninth Circuit’s analysis. The basic idea is that in order to qualify as a parody, a defendant’s work needs to target the original, not merely use it to convey a different, unrelated message.

Over the years, this requirement has caused some courts to engage in acts of contortion to find that a particular use qualifies as parody. For example, in Bourne v. Twentieth Century Fox, a judge in the Southern District of New York found that by juxtaposing the “saccharin sweet” song “When You Wish Upon a Star” with “I Need a Jew” in an episode of “Family Guy,” the Defendants were attempting to comment on the wholesome worldview presented by the original song and reveal it to be nonsense. I’m not sure anyone actually thought about things in those terms besides the lawyers defending the case, but it worked.

Somewhat similarly, ComicMix’s lawyers attempted on appeal to characterize their clients’ work as a criticism of the “banal narcissism” in “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” It didn’t work for ComicMix, with the court finding this “after-the-fact argument” to be “completely unconvincing.”

But the primary reason the court found that “Boldly” wasn’t a parody was because it didn’t ridicule the works of Dr. Seuss. Perhaps incongruently, the rules on parody encourage defendants to create works that copyright owners would presumably find more objectionable than works which simply pay homage to the original. In ComicMix, “Boldly” only “evoked” Dr. Seuss, as opposed to “ridiculing” it, so the defendant was out of luck.

Reading the court’s decision, I was reminded of Lombardo v. Dr. Seuss Enterprises, a 2017 Southern District of New York decision (later affirmed by the Second Circuit) in which the Dr. Seuss character Cindy Lou from “How the Grinch Stole Christmas” was reimagined as a trailer-park alcoholic for a one-woman Off Broadway play. In the play, the audience is told that Cindy Lou had a child with the Grinch, knocked the Grinch off a cliff after he tried to attack her, and served time in prison as a result. The court held that the play “recontextualized” the Seuss plot and rhyming style by placing Cindy Lou—a symbol of childhood innocence and naiveté—in “outlandish, profanity-laden, adult-themed scenarios involving topics such as poverty, teen-age pregnancy, drug and alcohol abuse, prison culture, and murder.”

In ComicMix, the defendant didn’t turn Dr. Seuss sufficiently on its head, which leads me to wonder whether the court’s ruling will cause would-be mash-up creators to resort to vulgarity to establish parody.

Oh, you master of understatement.

— ComicMix (@comicmix) December 21, 2020

Non-Parody Transformative Use

As I noted above, parody isn’t the only way that a court can find that a work is transformative. Any work may qualify so long as it adds some new expression, meaning, or message to the original.

While the Ninth Circuit’s opinion in ComicMix cited both Seltzer and Cariou, I don’t think the court did a particularly good job of explaining why the works in those cases “possess[ed] a further purpose or different character” while Boldly didn’t. The panel also didn’t offer much help to creators looking for guidance on exactly how to go about making a non-parodic transformative use.

That said, the fact is that “Boldly” was never a great test case for mash-up creators to begin with. The book is principally a Star Trek story, placed in a setting consisting of meticulously-recreated scenes from Dr. Seuss works. Whatever you think of the transformative nature of the Star Trek elements (which weren’t at issue in the case), the Seuss elements haven’t been transformed as much as they’ve simply been lifted from one set of works into another.

In some harmful discovery documents, ComicMix conceded that its book featured “slavish[] copy[ing] from Seuss.” In one instance, the book’s illustrator took seven hours to copy a single illustration because he “painstakingly attempted to make” the illustration in Boldly “nearly identical” to its Seussian counterpart.

A comparison of the works shows this on a graphic level. These illustrations, coupled with the previously-decided Penguin Books case, doomed ComicMix’s argument before the panel.

The Nature of the Dr. Seuss Works

The Seuss Works are creative. That weighs against fair use. There’s not much else to say on this factor.

The Amount and Substantiality of the Work Used

The amount and substantiality factor is one that’s often influenced by a court’s overall assessment of the other factors. If a work is sufficiently transformative, courts tend to assign this factor less weight and vice-versa. Here, not only did the court find that the defendant’s work wasn’t transformative, but ComicMix took a lot from Seuss. It wasn’t merely an evocation of the Seuss works’ overall feel, but a nearly verbatim replication of the precise composition and components of numerous Seuss illustrations.

The Effect of the Use on the Potential Market for or Value of the Copyrighted Work

“Effect on the market” is another factor that’s heavily influenced by the degree to which a court finds the work is or isn’t transformative. (Notice a pattern here?) The more transformative the defendant’s use, the less likely that it serves as a substitute for the original. And if a work is transformative, the defendant’s work is allowed to harm (or even destroy) the market for the original while still being protected.

Here, having found that “Boldly” wasn’t transformative, the court again focused on some pretty bad admissions by ComicMix. For example, there was evidence in the record that ComicMix timed the launch of “Boldly” to coincide with graduation season—the time of the year that “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” sales are traditionally strongest. There was also evidence that ComicMix recognized that Dr. Seuss Enterprises had branched out into the derivative works market. Unlike some fair use cases in which the defendant’s use doesn’t encroach on the market for derivative uses, here there was evidence that ComicMix thought that Dr. Seuss Enterprises would “want to publish [“Boldly”] themselves and give [ComicMix] a nice payday.”

In light of the overtly commercial motivations of defendants here, it would have been nice for the Ninth Circuit to have engaged in a discussion of the issues that some of the amici raised about non-commercial fan fiction, but I think the court reached the right result overall.

I’m seeing a lot of comments lamenting the 9th Circuit’s ruling in ComicMix. There are a number of reasons to criticize the opinion for its lack of guidance, but I think the outcome is correct on the facts. “Boldly” was never a good test case for mash-up creators. A thread:

— Aaron Moss/Copyright Lately (@copyrightlately) December 19, 2020

Conclusion

The bottom line is that the ComicMix outcome is good for rightsholders and bad for creators of commercial-oriented mash-ups that slavishly copy substantial elements from the original works while at the same time not holding them up to ridicule. Creators of mash-ups that don’t fall into this category should be careful, but will live to fight another day.

The court’s decision in Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix is below. As always, I’d like to know what you think. Let me know in the comments!

View Fullscreen