Over the past quarter-century, transformative use has become shorthand for fair use itself. The Warhol case gives the Supreme Court an opportunity to provide balance and flexibility to the doctrine.

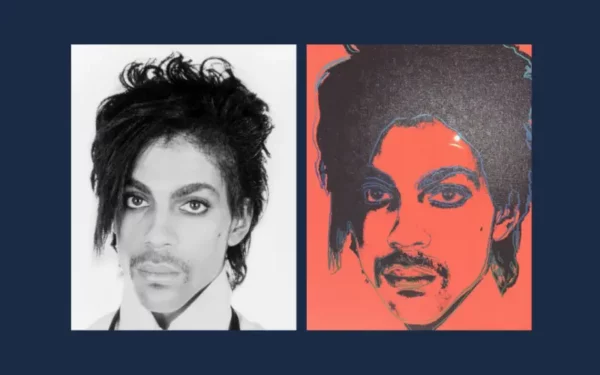

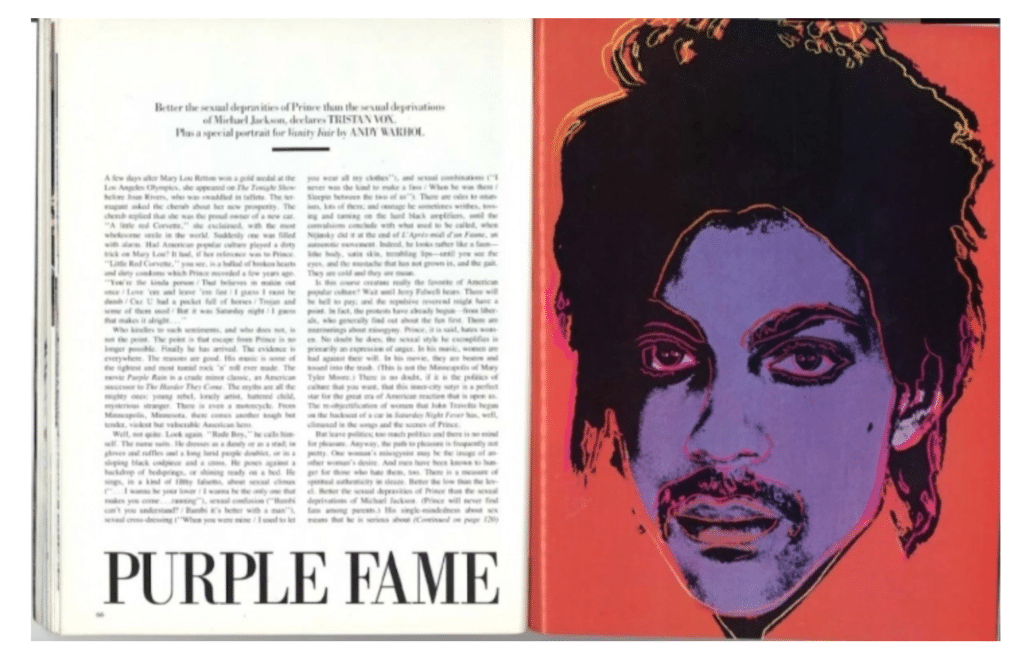

When I first heard that the Supreme Court had agreed to take up the fair use fight over Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series,” my first reaction was “Oh wow.”

As in, “Oh wow, I hope they know what they’ve gotten themselves into.”

After all, the last time the Court considered whether a creative work qualified as a “transformative” fair use under the Copyright Act was in 1994’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” case, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. That’s practically a lifetime ago, even for justices with lifetime appointments. (The transformative use doctrine did play a role in Google v. Oracle last term, but the Court went out of its way to emphasize the unusual and limited context of that case, which involved copyrights in functional computer code.) Of the Supreme Court members who will decide Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (Warhol), only Justice Thomas served on the Campbell bench.

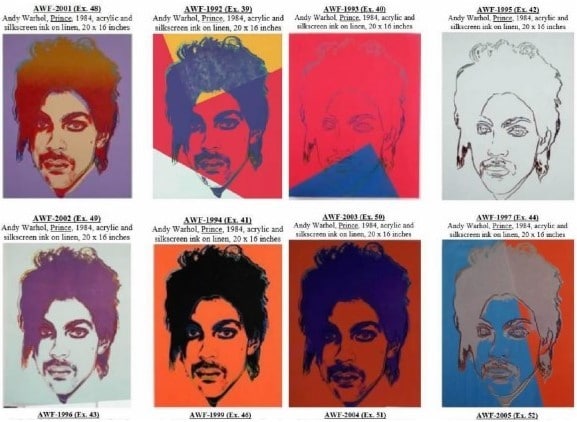

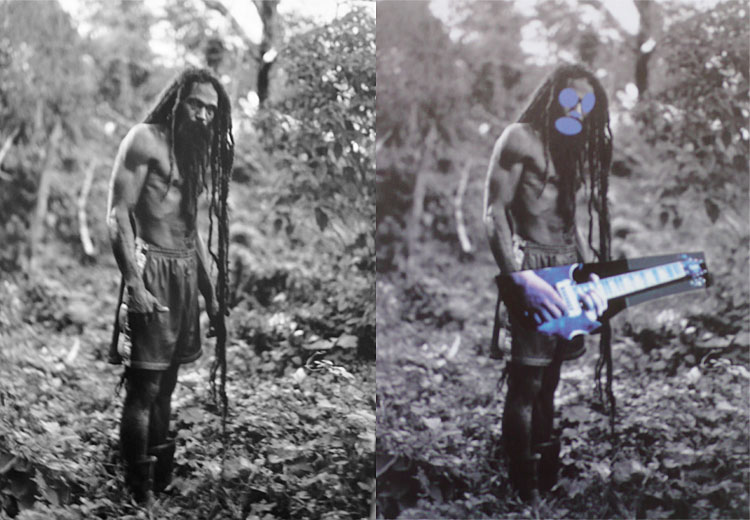

Justice Souter’s opinion in Campbell was on behalf of a unanimous court, but in the past 28 years, the fair use doctrine—and especially the meaning and application of “transformative use”—has become incredibly messy and practically unworkable. While the Andy Warhol Foundation’s petition for certiorari was ostensibly premised upon a circuit split between the Second and Ninth Circuits, fair use decisions have been all over the map, even within those courts. In other words, good luck trying to easily reconcile the Second Circuit’s decision in the Warhol case itself from its previous opinion in Cariou v. Prince. Or in squaring the broad language from the Ninth Circuit’s Seltzer v. Green Day with the result in Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. ComicMix, LLC.

Simply put, the Supreme Court is facing a monumental task now that it has agreed to review the Warhol case, especially because the question presented in the Warhol Foundation’s petition specifically asked the Court to determine the circumstances under which a work of art is “transformative.”

But is that the wrong question?

It’s certainly not the only question. There are at least four fair use factors (five if you count the unofficial “does the judge think you’re a jerk” factor). But there’s no doubt that in the quarter-century following Campbell, the other factors have taken a back seat to transformative use, which has all too often become the end-all, be-all of the fair use inquiry in a way that was never actually intended.

Fair use is supposed to be about balance and flexibility. Based on the data, that’s not how things have worked out. But there’s good news: it doesn’t have to be this way. With Warhol, the Supreme Court has the opportunity to restore some sense of equilibrium to fair use, regardless of how it rules on the merits.

Where Did “Transformative Use” Come From?

Before we get there, we need to figure out where we’ve been. If you’re read any of the hundreds of fair use opinions over the past 30 years (hopefully not all of them), you’ve no doubt run into the concept of “transformative use.” These words don’t actually appear anywhere within the fair use provision of the 1976 Copyright Act, and yet the concept has played a huge role in nearly all recent fair use decisions.

Back in the mid-1980s, the world was a different place. Ms. Pac-Man struck a blow for women’s rights. A young Joe Piscopo taught us how to laugh. And in the world of fair use, factor four was the belle of the ball. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises boldly proclaimed that the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work was “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.” Full stop.

Fast forward to 1990, and enter Judge Pierre Leval, an incredibly influential and knowledgeable jurist on the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, especially when it comes to copyright law. Back then, Judge Leval was a district court judge when he wrote an article for the Harvard Law Review called “Toward a Fair Use Standard.” In his article, Judge Leval argued that the fourth fair use factor was getting too much attention and that the first fair use factor (the purpose and character of the use) was really the “soul of fair use.”

For Judge Leval, a threshold consideration in determining if a use was justifiable was whether it served the purposes of copyright law—one that will “stimulate creativity for public illumination.” If a defendant used the plaintiff’s work “in a different manner or for a different purpose than the original,” Judge Leval suggested, the new work should be deemed a “transformative use” that furthers the objectives of copyright.

But it’s important to point out that while Judge Leval thought that transformation may well be a necessary component of fair use, he didn’t think it was sufficient—although this latter aspect of his article has been largely forgotten over the years. Where a work is transformative, the strength of the defendant’s justification still needs to be weighed against the remaining fair use factors which, according to Judge Leval, “focus on the incentives and entitlements of the copyright owner.”

Transformative Use Has Become Shorthand for Fair Use Itself

Judge Leval’s law review article ushered in a sea change of thinking about fair use and provided the underpinning for the Supreme Court’s formal adoption of the “transformative use” standard just three years later in Campbell. But in hindsight, “Toward a Standard of Fair Use,” may have been a tad too influential. Even though Judge Leval stressed that the transformative nature of a defendant’s work needs to be balanced against the other fair use factors, the first factor outcome has overwhelmingly dictated the overall fair use result.

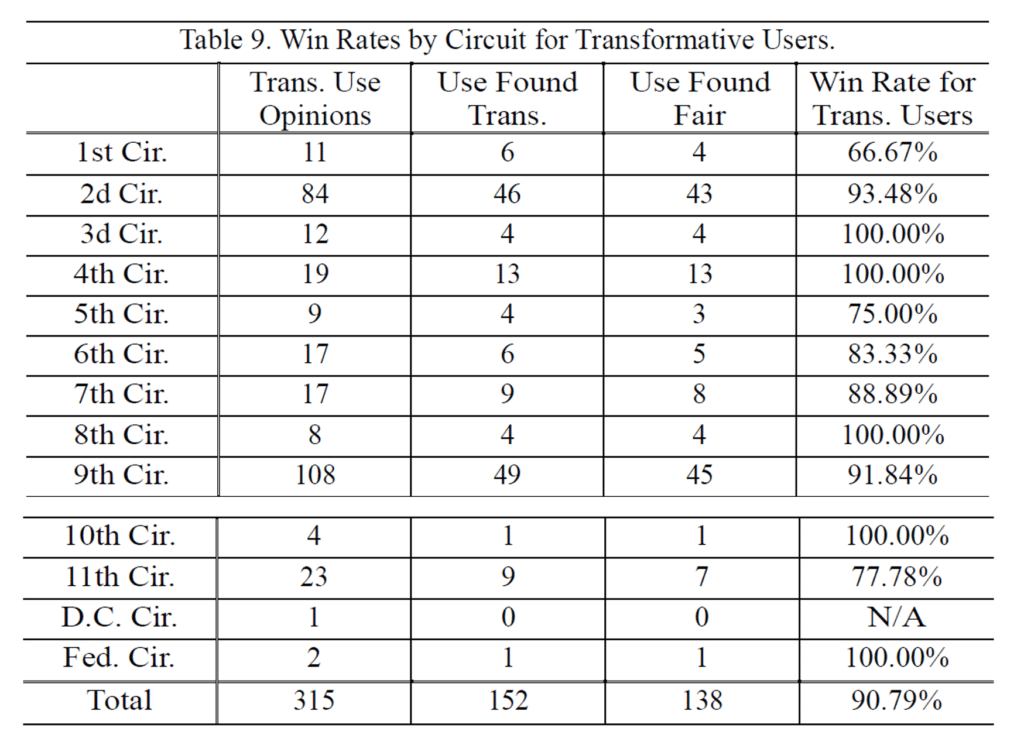

In a recent empirical study published in the Boston College Law Review called “Is Transformative Use Eating the World?” Clark Asay and his team analyzed fair use opinions between 1991 (the year after Judge Leval first coined the term “transformative use”) and 2017. They found that out of the 152 opinions during this period finding a use to be transformative, nearly 91% of those opinions also found the overall outcome to be fair. Some circuits have rates as high as 100%:

Conversely, parties which have been on the losing side of the transformative use inquiry have rarely prevailed on the overall fair use analysis. Of the 161 opinions that Asay reviewed falling into this category, only about 10% of defendants won on fair use after their works were found not to be transformative.

It’s hard to look at this data and not conclude that whether a putative fair use is characterized as “transformative” or “not transformative” has effectively driven the entire fair use inquiry. (A more cynical view would be that judges recognize how important transformative use has become, and feel pressure to label a particular use as “transformative” or “not transformative” based on their overall decision about whether the use is fair.)

A Standardless Standard?

The other major issue with the way “transformative use” has developed over the years is that nobody can agree on exactly what it means. It certainly hasn’t helped that the same word is used in the Copyright Act to define a derivative work (a work that is “recast, transformed, or adapted” from a pre-existing work), which in the absence of fair use is reserved to the copyright owner. Does the word “transformed” when used to describe a derivative work mean the same thing as the word “transformative” when used in the fair use inquiry? Does the answer depend on which side the court comes out on?

Even if we focus on Judge Leval’s (and Campbell’s) inquiry into whether the defendant has used the plaintiff’s work “in a different manner or for a different purpose than the original,” it’s not clear whether this inquiry should be based on the artist’s stated intent, the viewpoint of a so-called “reasonable observer” or (shudder) the “court as art critic.”

Making matters even more complicated, in the Warhol case, the Second Circuit appeared to reject all of these options, stating that judges shouldn’t be in the business of seeking “to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.” Nor, said the court, should the question of whether a work is transformative turn on the “stated or perceived intent of the artist” or the meaning or impression that a critic draws from the work. I’m not sure exactly what’s left. For a standard that ends up driving the fair use narrative, we’re really not getting much guidance.

And while looking at whether a defendant used the plaintiff’s work “in a different manner or for a different purpose than the original” may be straightforward enough in a parody case like Campbell, how useful is that analysis in a case involving contemporary art like Warhol? Remix culture is practically founded on the explicit rejection of “meaning” and “message.” Case in point: appropriation artist Richard Prince was once asked in a deposition to describe his message. His response: “[T]o make great art that makes people feel good.”

Yet it’s not uncommon to see fair use opinions in which the judge will engage in an act of contortion to find a purpose or a message that the parties never intended and that the public doesn’t really care about, and to then use that ad hoc rationalization to drive the rest of the fair use inquiry.

Away From Transformative Use?

Let’s be clear. There’s no reason that the transformative use inquiry needs to dictate the entire fair use outcome. It would be perfectly defensible, for example, for the Supreme Court in Warhol to find that Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series” did in fact use Lynn Goldsmith’s original photo for a new, different and “transformative” purpose, but that, on balance, the negative effect on Goldsmith’s licensing market (fourth factor) weighs against fair use.

It’s true that the fourth factor, as applied by some courts, has become an exercise in circular logic: a court will assume that a use could be licensed, and then conclude that it must be licensed. But this problem can be avoided so long as judges are discerning about distinguishing between legitimate markets from speculative ones. For example, the very genesis of Warhol’s Prince Series was a 1984 limited license agreement from Goldsmith allowing Vanity Fair to use her Prince photo as an artist reference. Goldsmith was paid and credited, but after Prince’s death, the Warhol Foundation licensed Warhol’s piece (which incorporated aspects of Goldsmith’s photo) to Condé Nast without permission, payment, or credit to Goldsmith.

It would also be useful for the Court to explicitly hold that the importance of “transformative use” may vary depending upon the nature of the work—giving it a greater role, for example, in a parody case than in a case involving visual art or (as in last year’s Google v. Oracle), largely functional software.

My point is not to suggest that any particular factor is inherently “better” or “worse” when analyzing fair use, or to suggest that any particular outcome should be favored. I simply note that the standard is supposed to be flexible. This means that the weight and significance given to each factor should be tailored to the facts and circumstances of each individual case.

Warhol Justice Watch: What Will The Supreme Court Do?

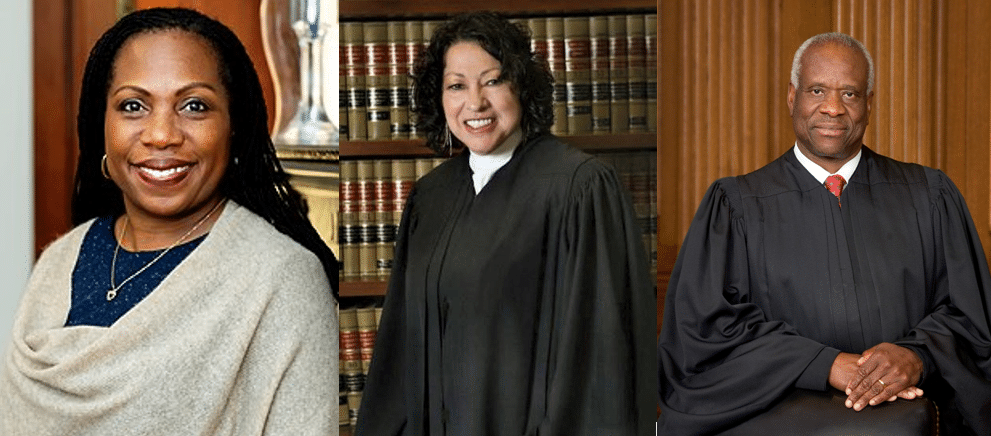

Given the composition of the Supreme Court next term, I actually think there’s a decent chance that Warhol won’t be won or lost on transformative use alone. The three members I’ll be keeping my eyes on most closely are Justices Jackson, Sotomayor and Thomas.

Ketanji Brown Jackson

Justice Breyer, who usually came down on the side of limited protection for copyrighted works, will be out, replaced by the newest justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson. Judge Jackson hasn’t decided a reported fair use case while on the bench (although she did dismiss a pretty bizarre infringement lawsuit against several record labels and studios a few years ago as a district court judge).

More recently, Judge Jackson responded to a number of written copyright-related questions posed during her confirmation hearings, and on the topic of fair use stated her view that the fourth fair use factor (effect of the use upon the potential market) was the most important, citing Harper & Row. Notably, Judge Jackson didn’t mention the first factor or “transformative use” at all in her response. While it’s certainly possible that Judge Jackson’s response was simply designed to defer to Supreme Court precedent, it’s doubtful that Justice Breyer would have answered this question the same way. He certainly didn’t cite Harper & Row for this proposition in his Google v. Oracle opinion last term.

Sonia Sotomayor

Justice Sotomayor is definitely someone to watch closely during oral argument in Warhol. While a district court judge in the late 1990’s, she actually accomplished the rare feat of deciding a fair use case by finding that the defendant’s work was transformative, but that the remaining factors weighed against fair use.

The case, Castle Rock Entertainment v. Carol Publishing, involved a copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the producer of Seinfeld against the author and publisher of “The Seinfeld Aptitude Test” (SAT), an unauthorized trivia book about the show. Then-Judge Sotomayor found that the first fair use factor weighed in defendants’ favor: “By testing Seinfeld devotees on their facility at recalling seemingly random plot elements from various of the show’s episodes, defendants have ‘added something new’ to Seinfeld, and have created a work of a ‘different character’ from the program. It may even be said that defendants have identified a rather creative and original way in which to capitalize upon the development of a ‘T.V. culture’ in our society; a culture in which the distinction between fiction and fact is of declining consequence, and in which people are as concerned with the details of the former as the latter.”

But Judge Sotomayor didn’t stop there. Instead, she explicitly followed the guidance offered in Judge Leval’s law review article, noting that even where a work is transformative, “the crux of the fair use analysis remains,” requiring the court to “proceed with a careful consideration of the remaining three factors, while merely granting defendants an advantage at the outset.”

Judge Sotomayor concluded that the remaining three fair use factors all weighed in favor of Castle Rock: Seinfeld was a highly successful fictional and creative work; defendants identified and used the most important elements of Seinfeld and incorporated them into their book, without including much additional material. And while SAT could not be expected to reduce interest in Seinfeld, or even to occupy derivative markets that the plaintiff necessarily intended to enter, the court found that the market for non-critical, non-parodic trivia books “is one that should properly be left to plaintiffs’ exclusive control.”

The district court opinion in Castle Rock was affirmed on appeal. However—and by now this shouldn’t come as a surprise—the Second Circuit analyzed the fair use issues in Castle Rock in the same way most courts have done so, with a finding on transformative use that lines up precisely with the other fair use factors. In ruling that all of the factors weighed against fair use, the appellate court rejected Judge Sotomayor’s first factor conclusion and held that any transformative purpose possessed by the book was “slight to non-existent.”

Clarence Thomas

Can you name the only Justice on the Supreme Court who’s ever cited Harper & Row for the proposition that the effect upon the potential market for or value of a plaintiff’s copyrighted is “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use?”

That would be Justice Thomas, in last year’s dissenting opinion in Google v. Oracle. Justice Thomas (joined by Justice Alito) also took the majority to task for finding that Google’s use of Oracle’s software declaring code was transformative when, in his view, the work “simply serves the same purpose in a new context.” Thomas would have focused on the fourth fair use factor, and noted that Google interfered with Oracle’s licensing opportunities by using its code.

The big question is whether Justice Thomas will continue to ride the fourth fair use factor in Warhol, while at the same time finding the Prince Series to be transformative, as he did with “Oh, Pretty Woman” in Campbell.

The Bottom Line

While all of this theorizing and handicapping is fun for copyright nerds like me, there’s a much larger issue that we shouldn’t lose sight of: Fair use is important. It’s one of the few copyright concepts that’s encountered regularly by regular people (e.g., anyone who posts any sort of repurposed content on social media). And yet the doctrine has become totally unpredictable in all but the clearest cases. As Larry Lessig once said, “fair use in America simply means the right to hire a lawyer.” A lawyer, I should add, who probably won’t be able to give you a clear answer either. Judges don’t fare much better: just consider that the appellate panels in Cariou, ComicMix, and Warhol all reversed lower court decisions by the well-meaning district court judges below.

Even if the Supreme Court uses Warhol as an opportunity to restore balance when applying the fair use factors, it’s critical that the Court does so in a way that makes sense to judges, lawyers, and members of the public who will then be required to rely on its decision. If the Court leaves us with a ruling that’s defensible based on the facts, contains a sensical application of the law, and—above all else—feels “fair,” it will be a major success, regardless of the outcome.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Hit me up in the comments below or on social media @copyrightlately. Thanks for reading!

2 comments

It’s disappointing to learn that Justice Jackson thinks the fourth factor is the most important, but I hope she’ll be convinced otherwise. Nice catch on Justice Sotomayor as the District Judge on the Seinfeld case.

*I hope it goes without saying that I supported Justice Jackson’s nomination regardless of any copyright principle.

Of course, Warhol wins on the fourth factor. People want to license the Warhol image because it’s a Warhol (in addition to the fact that he transformed Prince’s facial expression). Ditto Cariou v. Prince – no effect on Cariou’s tiny market, if it existed at all. (I seem to remember that he said in his deposition that he wasn’t authorized to sell photos of his subjects.) But I suspect the Supreme Court isn’t going to focus on a balance of factors, but rather degree of ‘recontextualization’ required and what factual showing needs to be made. (The artist’s self-justifications? art critics? university professors? etc.) Personally, I’m hoping for broad protection of new (transformative) works. While this battle is going on in the art world, when it comes to sound recordings, courts have spent a over 30 years denying the reality that most sampling is not only transformative, but also stimulates interest in, and sales of, the sampled work.