Inside HitPiece, an NFT site where the only things in scarce supply are common sense, self-awareness and basic decency.

Last week’s HitPiece fiasco may go down as the biggest debacle in the brief history of NFTs, combining audacious hubris and disastrous execution with an inevitable yet spectacular crash and burn. It’s the kind of thing that typically only happens when a company spends its start-up budget on celebrity launch parties instead of a competent legal team.

The HitPiece Business Model

For the uninitiated, Hitpiece.com was, at least as of a week ago, a beta internet service that claimed to let fans buy and resell NFTs of their favorite songs. According to the site’s now-scrubbed website, “Each HitPiece NFT is a One of One NFT for each unique song recording. Members build their Hitlist of their favorite songs, get on leaderboards, and receive in real life value such as access and experiences with Artists.”

Part of HitPiece’s strategy was to drive anticipation by initially only offering one NFT for each artist. Following a seven day auction, “the NFT is minted and delivered to the winner’s custodial wallet,” at which point the next NFT by that artist would be offered for sale. Purchased NFTs could also be resold. In the example below, a “song” from “The Lion King” looks to have been purchased for $15 at the initial auction, and later resold to another user for $105.

HitPiece, We Have A Problem

In a January 24 interview with the “Business Builders” podcast that has since been deleted (are you sensing a pattern here?), HitPiece co-founder Rory Felton bragged that it was “the mission of the company to help artists create a billion dollars.” According to Felton, “Artists get royalties from not only the initial auction, but also every time it’s traded so it becomes your perpetual revenue stream for artists and rights holders, which is really cool.”

Incredibly, however, HitPiece didn’t ask for or receive permission from the vast majority of the artists and record labels featured on its site, many of whom were completely blindsided when they found out that their work was being offered for sale. We’re talking about everyone from small-time labels and artists to the likes of Disney, Nintendo and Taylor Swift, none of whom are exactly shy about protecting their IP rights.

“And that typically begs the question about rights…”

The world of NFTs is littered with examples of startups run by folks who either don’t know, don’t understand or don’t care about obtaining permission from the owners of the underlying works for the NFTs they’re advertising and minting. What makes the HitPiece story unique, and particularly shocking, is that its founders did know, and at least claimed to care about artists’ rights.

As noted above, one of HitPiece’s co-founders is Rory Felton, who for years ran a record company and music publishing company, among numerous other music industry ventures. The other co-founder is Michael Berrin, better known as MC Serch from late-80’s hip hop group 3rd Base.

The site has the financial backing of Blake Modersitzki and Jeff Burningham, both Utah-based venture capitalists, the latter of whom was an early investor in Spotify. According to Felton’s January podcast interview, HitPiece recently raised a seed round of $5 million in funding.

During his podcast interview, Felton was asked what kind of artists were affiliated with the HitPiece site. His lengthy answer is worth quoting in full:

“We’ve got everyone. Because we built this on top of Spotify’s API, it is the full gamut, you know. And that typically begs the question about rights. And rights in music is a really complicated issue. People probably aren’t aware, but Spotify just as an example, has been involved in dozens and dozens of rights disagreements with rightsholders, be it on not only songwriting but also the master rights and even also artwork rights. And now there’s a huge disagreement with the comedian population around what rights do comedians get for writing a joke because I don’t think that actually exists in copyright law yet. So there’s a lot of nuances out there. The way our smart contracts are written is like the money is always credited to the rights holder’s account and it’s absolutely our aim for them to always get paid, like it’s the mission of the company to help artists create a billion dollars and I think we can get there.

Rory Felton, “Business Builders – Boise” Podcast, January 24, 2022

So, to recap: Felton understood that music and artwork rights “was a really complicated issue”; understood that it was critical for artists and labels to get paid when their work was used; and understood that those artists and labels have fought to protect their intellectual property when they believe it’s been used without permission.

And yet, incredibly—unfathomably—HitPiece proceeded to offer NFTs on behalf of every artist on Spotify without so much as informing the artists or labels, let alone getting their permission. What’s worse, Felton publicity represented that HitPiece was, in fact, doing “tons” of deals with “big big artists we can’t mention just yet [and] tons of companies”—none of which, apparently, was remotely true.

So, What Exactly is HitPiece Selling?

HitPiece’s target demographic, according to Felton, was traditional music fans as opposed to NFT aficionados or early tech adopters. The site, for example, allowed buyers to purchase its NFTs using credit and debit cards, and didn’t accept cryptocurrency as a method of payment. (It’s not entirely clear that the public could even verify the authenticity of transactions made in the HitPiece ecosystem, which has always been touted by supporters as a key benefit of NFTs stored on the blockchain.)

According to HitPiece’s FAQ, “Each HitPiece NFT is a One of One NFT for each unique song recording.” Music fans reading this would certainly be forgiven for thinking that they were acquiring something of value—a unique asset tied to their favorite song if not the underlying music itself.

But this wasn’t the case. HitPiece’s website looks to have been comprised almost entirely of massive amounts of metadata scraped from Spotify’s publicly-available API, including album cover images, artist names, and track listings—although none of the music itself. Buyers were basically acquiring nothing more than the ability to say that they “owned” a particular song—but without any actual ownership and with their bragging rights confined to the HitPiece ecosystem.

In fact, as Felton admitted during his podcast interview, the company was essentially just selling “trading cards for songs.” The idea, he said, “is that you get to show off to your friends or people around the world that you own the greatest HitList that you can create of all your favorite songs.” In a nutshell, HitPiece was asking its users to pay for something that any of them could already do for free simply by sharing their Spotify playlists.

And there was nothing “exclusive” or “official” about any of this. While the site claimed that artists would “provide NFT owners access and experience” as a benefit to customers, HitPiece doesn’t look to have had any agreements in place that would actually ensure this happened.

HitPiece also represented that “Each time an artist’s NFT is purchased or sold, a royalty from each transaction is accounted to the rights holders account.” But without any agreements in place, the idea of a “credited royalty” is really nothing more than a down payment on future legal damages.

Cue the Lawyers

On Friday, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) sent a letter to an attorney representing HitPiece, demanding that the site permanently stop infringing musicians’ intellectual property rights and that it account for all of the transactions already made. The letter also demands that HitPiece “preserve all documents and other evidence that is in any way related to this matter, including a complete copy of the Hitpiece.com website itself, as well as any and all physical and electronic documents (including, without limitation, emails, texts, chats, and social media pages).”

Artists and labels are going to need to act fast to make sure that relevant evidence is actually preserved. As I noted above, the “Business Builders” podcast containing a number of critical Felton admissions has already been deleted. (Thankfully, it’s been archived by musician and artists’ advocate David Lowery, who’s done some fantastic investigative work into HitPiece on Twitter over the past week.)

A number of the executives’ social media posts also appear to have been deleted, including photos of a launch party HitPiece held at Art Basel in Miami, for which it hired Artz, Busta Rhymes, Noreaga and MurdaBeatz to perform.

As far as potential legal claims go, HitPiece’s use of the artists’ names, images and album artwork on its website would likely give rise to claims for copyright infringement (for the artwork), as well as various causes of action rooted in passing off, misappropriation of name and likeness, and unfair competition. But I think this is one of those situations in which intellectual property claims are really going to take a backseat to outright fraud.

Over the past week, HitPiece has responded to outraged artists by denying that any music has been “sold, streamed or bid on.”

But the fact that HitPiece wasn’t actually selling NFTs that were associated directly with the sound recordings is really beside the point. The site certainly represented that it “lets fans collect NFTs of your favorite songs,” and at least some purchasers seem to have believed that’s exactly what they were getting. As an example, take a look at this tweet from a HitPiece customer who apparently thought he was buying a “priceless” audio NFT for his cancer-stricken father:

HitPiece told at least one artist who asked why his music was on the platform that it was “most likely from your music distributor”—which appears to be a blatant fabrication:

So far, HitPiece has responded to the numerous tweets calling it a scam operation by “clarify[ing] we are definitely not a scam.” (I’m sure this will put everyone more at ease about the whole situation, especially when the company is refusing to put out any public statements, as opposed to telling people to “DM us.”)

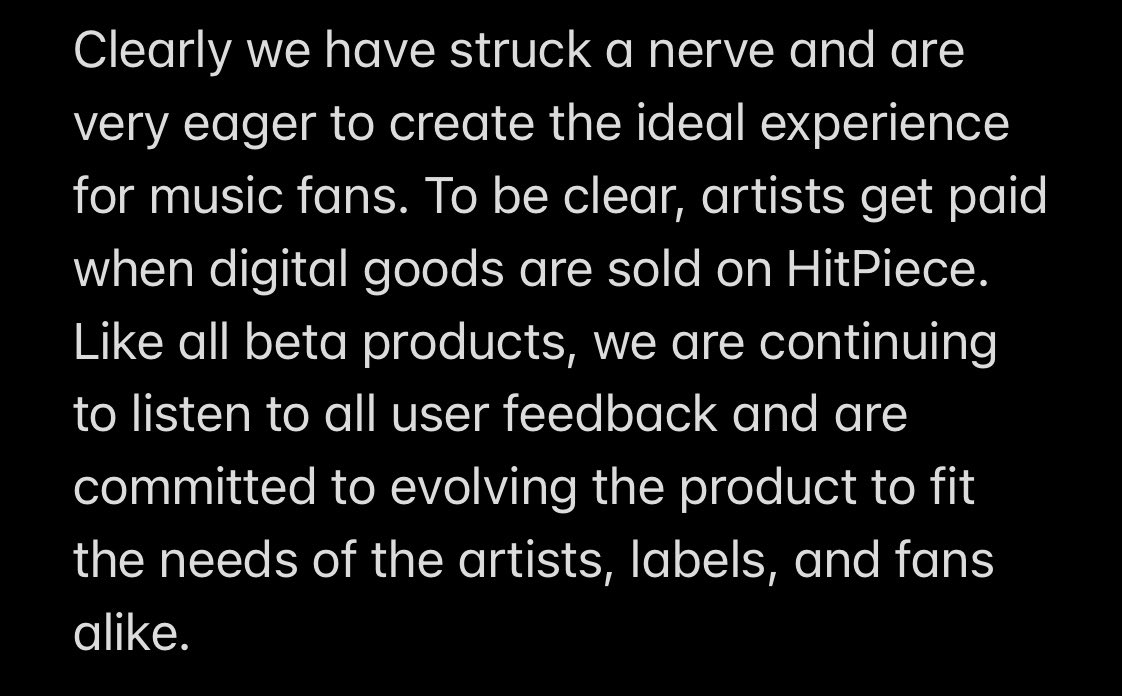

“We Have Struck a Nerve”

The only official statement put out by HitPiece over the past week didn’t contain any semblance of an apology, but instead tried to recast the company’s actions as simply having “struck a nerve”—which needless to say, didn’t go over well with the artistic community.

What’s Next?

As of this writing, all of HitPiece’s content has been removed for now, replaced with a vague and ultimately meaningless platitude:

The company may have started the conversation, but I have a feeling that conversation is going to continue via under-oath testimony in several lawsuits.

The HitPiece situation is certainly not the first time the words “NFT” and “scam” have been used in the same sentence, and it definitely won’t be the last. But historically, the scamming has been carried out by thinly-capitalized, fly-by-night operators, many of whom apparently don’t believe that the legal system even applies to the virtual world. HitPiece, on the other hand, was backed by lots of money and the so-called sophistication of experienced former music industry executives. These individuals clearly recognized that “rights” were an actual thing and must have known that what they were doing wasn’t legal or ethical.

This could be chalked up to a conscious strategy of asking forgiveness rather than permission, but I just can’t believe the HitPiece executives could have really thought that their site was going to be well-received given the circumstances of its launch. Even within an NFT industry that’s forced to justify its very existence on a regular basis, I find this one truly inexplicable.

I’d love you get your take. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments below or on your favorite social media account @copyrightlately.

3 comments

Any thoughts on this being a deliberate ploy to create controversy to put them in the box seat for future deals regarding music NFT transactions?

That’s as good a guess as any as to the motivation – but showing proof-of-concept via a public beta without getting the rights first is an incredibly risky way to proceed. And it’s not like these guys had anything proprietary to offer.

The site, for example, allowed buyers to purchase its NFTs using credit and debit cards, and didn’t accept cryptocurrency as a method of payment. Thank you for sharing your great post!