NFT enthusiasts envision a fictional world of fan-owned creative properties and character crossovers. Just don’t forget about real world copyright law.

♫

NFTs were minted

Money was advanced

The underlying contracts

Never got a glance

Dreams of exploitation

From Florida to France

But no rights were acquired

The kids don’t stand a chance

— “The Kids Don’t Stand a Chance, Aaron’s Version” (with apologies to Vampire Weekend)

While some NFT entrepreneurs are perfectly content to sell images of trash cans for $250,000 and call it a day, others have been thinking much, much bigger. They envision a world in which NFTs can unlock the potential for crossovers of different fictional characters and creative content. Some call it a “decentralized Disney,” a virtual world similar to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, except that properties would be owned by diverse groups of fans and collectors instead of a single company.

You want to make a buddy film about a Bored Ape and a CryptoPunk trying to get home in time for Thanksgiving? Or about a pair of underachieving Gutter Rats who are sent back to a local high school to bring down a synthetic drug ring? What about editing some NBA Top Shots moments to create a fantasy matchup between Michael Jordan and Steph Curry? It’s the kind of virtual utopia that’s hard to imagine in the world of traditional media because, you know, “rights.”

Ok, ok, it’s actually not that simple, which means now I get to wake you up from your NyQuil-fueled fever dream and be the killjoy who reminds you that the metaverse isn’t some kind of self-governing Florida special district in which real world laws don’t apply.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m all in favor of using blockchain technology to facilitate the exchange of creative content. But simply putting the word “rights” in scare quotes doesn’t make them “so called” rights. And call me old-fashioned, but I also happen to believe that people who shell out 600 grand for a picture of a cartoon monkey deserve to know what they’re actually buying.

The good news is that even though this stuff is widely misunderstood, it isn’t all that complicated. If you remember just a few concepts that I’ll discuss in this post, you’ll be way ahead of the game when it comes to buying, selling and exploiting creative works, whether it’s in the metaverse or here in the boring old regularverse.

Buying Objects ≠ Buying Copyrights

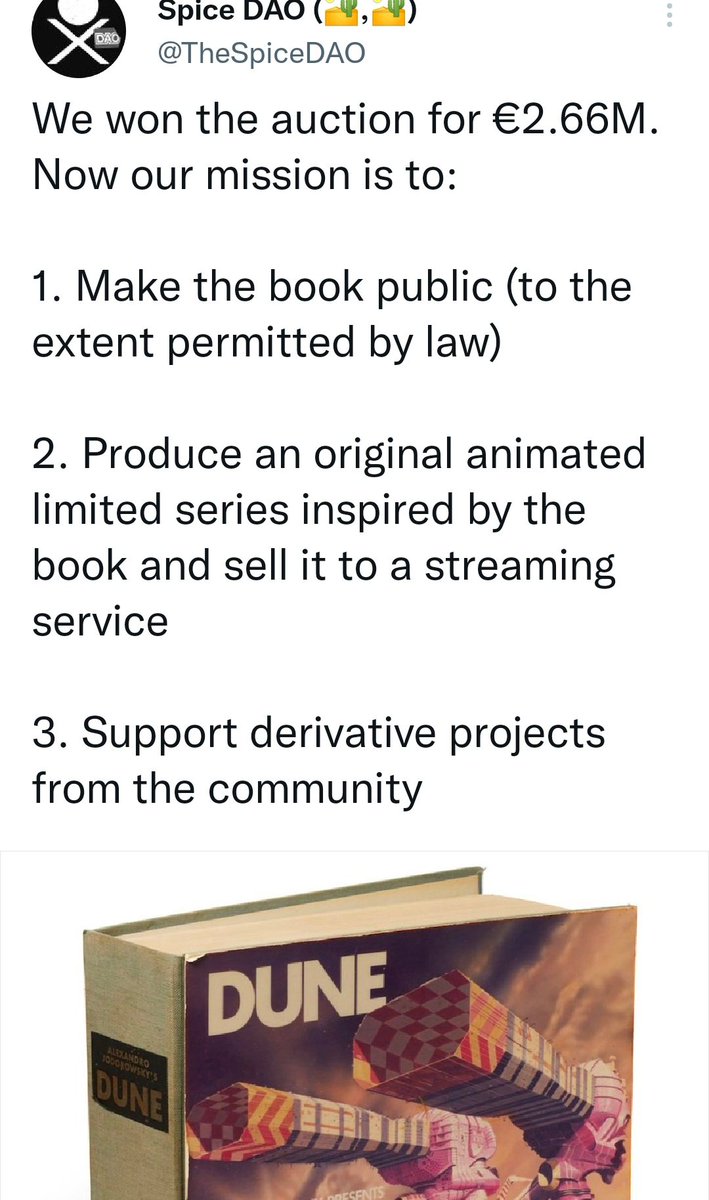

The first thing that’s important to understand is that buying a copy of a creative work, even if it happens to the only copy in existence, doesn’t give you any copyright interest in the work. So, if you buy a copy of “Dune,” you can read it. You can also tell your book club that you read it even though you really stopped at page 136. What you can’t do is make your own “Dune” movie. For that, you’d need an assignment or license from the owner of the underlying copyright. The same rule applies to digital artworks sold as NFTs.

This may seem obvious, but earlier this year an anonymous cryptocurrency-backed group known as Spice DAO was mocked mercilessly for paying around 3 million dollars for a rare copy of “Dune,” under the apparent misconception that by purchasing the physical book they had also acquired the right to produce a new animated series based on the property. The story is so ridiculous that I still haven’t decided if it was all just a massive troll. Either way, don’t be like those guys.

Chain of Title is Your Friend, aka “Teenage Mutant Ninja Fumble”

In other cases, NFT enthusiasts were told that the backers of a project had in fact acquired a license to exploit the copyright interest in an underlying creative work, only to find out later that this was wishful thinking—or even worse, an outright scam.

Just this week, a start-up purporting to “own the NFT digital rights” in the original 1987 “Teenage Mutual Ninja Turtles” cartoon series had its Twitter account suspended after questions emerged about the legitimacy of the project.

The folks behind @TMNTNFT faced questions from the start about exactly how they had acquired rights to produce new animated works based on the TMNT property. As of a few months ago, everyone thought the Turtles NFT rights were already spoken for, as ViacomCBS (since renamed Paramount) publicly announced that it had entered into a strategic partnership with NFT company RECUR to “create a unified environment where fans can buy, collect and trade NFTs as digital products and collectables” across Paramount’s IP portfolio.

And yet in February, TMNT NFT showed up, and almost instantly had its account verified by Twitter. Richard Blade has been whining for 15 years about not having a verified Twitter account and these turtle guys got one in less than a month. They must be legit, right?

Still, folks were skeptical, at least until the end of March, when TMNT NFT posted a lengthy “official statement” on Medium attempting to allay concerns expressed by the fan community. The group behind the project noted that “In the world of decentralized projects, we understand there are those that have been less than honest. Due to this reason, we wanted to write to our community and clarify this project’s legitimacy.” The statement went on to explain that the group had acquired rights from a company called Squemme Productions, which itself had acquired “the exclusive IP for the first 130 episodes of TNMT 1987” from Poly Productions/IDDH.

The TMNTNFT group even obtained a letter from an IP lawyer in France, who attested to the legitimacy of the project. (Although I should point out that the lawyer’s letter only references the group’s right to “extract” particular “images” taken from the the original episodes in the form of NFTs—which seemed to call into question the group’s earlier claim that it had rights to create new animated videos based on the property.)

According to the group’s statement on Medium, the rights held by ViacomCBS in “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” did not extend to the 1987 animated series: “Our legal team is also working to get in direct contact with Viacom to keep things clear between all parties. This will prevent anyone from stirring up trouble for no reason.”

Presumably, none of this sat well with RECUR or Paramount, which reportedly was exploring its legal options against the TMNTNFT collective. Then, last week, the group suddenly reversed course, releasing another “Official Statement” which revealed that, in fact, it had been sold a “fake IP rights” contract by Squemme Productions:

TMNT NFT expressed hope that it could continue the Turtles project “hand in hand with Paramount.” But given that these guys don’t seem to be coming to the table with anything other than an admittedly fake IP rights contract, I wouldn’t hold my breath.

Could investors keen to buy into the Teenage Mutual Ninja Turtles NFT hype have avoided getting stuck in the sewer? Definitely. It would have taken a bit of due diligence, but not much. The warning signs were all there. For starters, as the “Rull Pull Finder” Twitter account noted, Squemme Productions has only been in existence since July 2021. Meanwhile, television rights management company IDDH (International Rights and Divers Holding), the supposed source of Squemme’s IP interests, liquidated all of the assets it had over twenty years ago and looks to have been defunct since 1999. And a quick review of U.S. trademark office records reveals that Viacom obtained rights in a broad array of TMNT marks after a highly-publicized purchase from the Mirage Group in 2009.

Again, this is all based on a quick review of publicly available records. Anyone in serious negotiations to acquire an interest in a property as popular as “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” should have asked to see the entire chain of title relied upon by Squemme in order to satisfy itself that it wasn’t getting a bill of goods. (By the way, if anyone reading this speaks French, let me know if Squemme is pronounced like “scam,” because if so, that would be nuts.)

Want to Create New Derivative Works? You Should Probably Read The License

Let’s assume that one of the French production companies involved in the creation of the original “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” animated series had held onto certain limited rights in those particular programs, and went on to license those rights to TMNT NFT. This still wouldn’t necessarily have given the buyer carte blanche to create new derivative works featuring the characters, as opposed to, perhaps, digital screengrabs from individual episodes. (This seems to be the distinction that attorney Marc-Olivier Deblanc was trying to draw in his March 31, 2022 statement.)

While selling static digital images may be the typical current use case for NFTs, proponents of a decentralized Disney are looking to go much further: They envision an ecosystem in which acquiring an NFT would give the buyer the right to exploit the underlying character IP in new derivative works, divorced from any specific images.

So how does one get to this magical place in which characters of different shapes, sizes and origins can interact in new and exciting ways? You may not may want to hear this, but hopefully by now you know that you’re going to need the rights. In particular, you’ll need a license to create derivative works, which is one of the exclusive rights granted to copyright owners in section 106 of the Copyright Act.

In order to know if you’re acquiring the ability to create derivative works, it’s important to carefully read the terms and conditions that govern the sale or license. It also wouldn’t be a bad idea to hire a lawyer to read them. This is because the devil is in the details, and unfortunately, issuers of NFT projects haven’t always been great about explaining those details in an easily understandable way.

Take the Terms & Conditions governing the Bored Ape Yacht Club, which you may be interested in if you’ve plunked down half a million dollars for a picture of a stoned primate. Here’s the first clause, section (i), dealing with ownership of the Bored Ape NFTs:

“i. You Own the NFT. Each Bored Ape is an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain. When you purchase an NFT, you own the underlying Bored Ape, the Art, completely. Ownership of the NFT is mediated entirely by the Smart Contract and the Ethereum Network: at no point may we seize, freeze, or otherwise modify the ownership of any Bored Ape.”

Sounds pretty good, right? When you buy the NFT, you own the “underlying Bored Ape, the Art,” completely. BAYC can’t seize it or freeze it. But don’t stop reading yet, because there are a few more terms:

What’s all this about? If you “own” the NFT, and you “own” the underlying Bored Ape “completely,” why is the issuer Yuga Labs giving you any sort of license, let alone one that’s subject to your “continued compliance” with its terms?

Remember the distinction I made at the beginning of this post about the difference between owning a piece of art and owning the underlying copyright in the art? In section (i) of the terms, Yuga seems to be saying that when you buy a Bored Ape, you own the NFT (the token) and the digital artwork that’s associated with the NFT. But notice that Yuga doesn’t say anything about you owning the copyright, which is the right to control all of the different ways in which the artwork and underlying character could theoretically be exploited. That would require a copyright transfer via a signed writing from Yuga. Sections (ii) and (iii) of the Terms and Conditions appear to provide, at best, a limited license to use the artwork associated with the Ape you’ve purchased for certain commercial and non-commercial purposes.

But what’s really unclear about the Bored Apes terms and conditions is the extent to which Yuga is giving Apes owners a broad license to create new derivative works based on the underlying characters. While the word “Art” is capitalized, the term isn’t actually defined anywhere in the license. The terms provide an example of owners having the right to copy the image of the particular Ape they’ve purchased onto T-shirts and other merchandise. If you sell 46,000 T-Shirts of your Ape on Redbubble, you might even turn a profit.

But it’s not clear that owners are legally obtaining any right to create new derivative works that go beyond mere “copies of the Art” (i.e., reproductions of the static image of each particular Ape). To be sure, it doesn’t appear that Yuga has actually objected to Ape owners creating and exploiting derivative projects that go far beyond the the use of static images. An example, is the popular and ambitious “Jenkins the Valet” Ape project.

But just because the owners of the underlying Ape IP haven’t put a stop to these projects doesn’t mean that they’re legally guaranteed by the BAYC terms and conditions. Unfortunately, this means that you may not be able to shop the rights to a new animated project featuring your Ape getting involved in all sorts of wacky hijinks without facing some uncertainty about the project’s legal status.

What’s more, the BAYC license doesn’t look to be exclusive to the owner of each individual Ape, which means that Yuga Labs would retain the ability to use and monetize the art itself—including by licensing the right to create derivative works of “your” Ape to others.

The Bottom Line

This is definitely not all there is to know about the interplay between NFTs and copyright, and there are all sorts of issues I haven’t dealt with in this post, mainly because I wanted to keep things as simple as possible and also because I need to go to sleep. If you’re interested in learning more, I’d recommend checking out Cornell Law Professor James Grimmelmann’s recent Medium article, “Copyright Vulnerability in NFTs.” In the article, Grimmelmann explores a number of the currently unanswered questions involving the licensing of NFTs. One particularly thorny issue involves trying to figure out what happens to existing copyright licenses in the event an NFT is subsequently resold.

For now, here’s a quick recap of my key takeaways:

- First, just because you buy an object associated with an NFT, whether digital or physical, this doesn’t mean that you’ve acquired rights in any underlying intellectual property associated with the asset.

- Second, if someone is claiming to offer rights in underlying IP, it’s important to carefully investigate the seller and the property’s chain of title, because you can only acquire rights that the seller actually possesses.

- Third, your ability to exploit and create new derivative works based on assets associated with an NFT will be governed by both copyright law and contractual terms and conditions, and you should know what they say before you start your project.

If you have any questions of a general nature, I’ll do my best to answer them in the comments section below. You can also weigh in on your favorite social media platform @copyrightlately. As always, thanks for reading!

1 comment

Thank you so much for your enormous kindness, generosity and wisdom. Your legal expertise is a breath of fresh air in the NFT space. Your guidance is my touchstone.