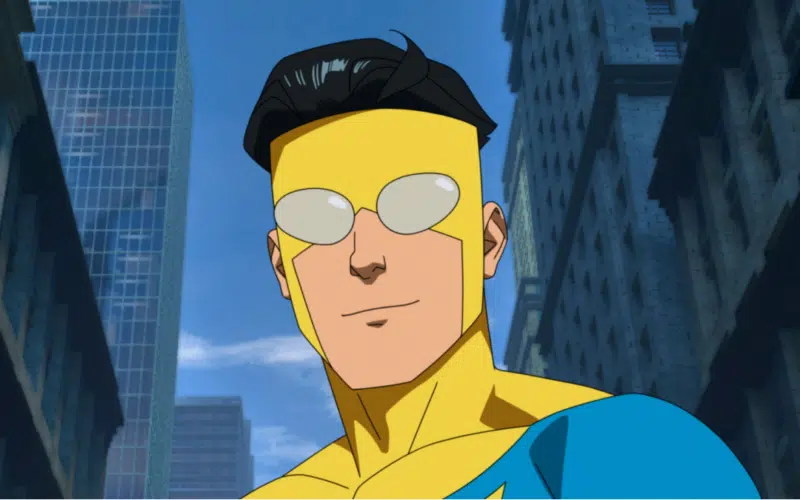

As a new lawsuit involving the popular comic book and animated series “Invincible” shows, the failure to properly document the copyright status of a jointly-created work at the beginning can lead to messy consequences later.

Can someone be tricked into giving up copyrights he may never have owned in the first place? That’s just one of the interesting questions raised by a new lawsuit filed by William Crabtree, colorist of the first 50 issues of the comic book series “Invincible,” against the series’ writer and co-creator Robert Kirkman.

Crabtree v. Kirkman

Crabtree claims that Kirkman talked him into giving up co-ownership rights in “Invincible” by asking him to sign a document in 2005 that Kirkman represented would make it easier to market the work to licensees, but which wouldn’t affect any of Crabtree’s rights. The “Certificate of Authorship” (which Crabtree allegedly signed without reading) in fact purported to characterize all of Crabtree’s contributions to “Invincible” as a “work made for hire” in favor of Kirkman’s company. Crabtree claims that Kirkman later licensed “Invincible” television rights to Amazon Studios and denied the existence of a oral agreement to give Crabtree a share of the revenue.

Crabtree’s complaint (read here) seeks a declaration that he’s a joint author of “Invincible” with an undivided ownership interest in the entire work and that the Certificate of Authorship is invalid. He also asserts claims for fraud and breach of the parties’ oral agreement.

Contributors to creative works are of course free to reach whatever type of agreement they’d like regarding revenue splits—although it’s definitely preferable to put things in writing, especially when it comes to proving up the contract in a lawsuit. Crabtree contends that his agreement with Kirkman entitled him to 20% of single issue sales of “Invincible” as well as 10% of any revenues generated from film or television exploitation of the work. In support of his position, Crabtree asserts that even after he signed the Certificate of Authorship, Kirkman paid him thousands of dollars in connection with revenue earned from television and film licenses with MTV and Paramount. But when it came to the license for the Amazon series, Kirkman denied that Crabtree was entitled to a share, and characterized prior payments as mere discretionary “bonuses.”

The Requirements for Copyright Joint Authorship and Co-Ownership

Having an agreement to receive revenue from a copyrighted work isn’t the same thing as owning an interest in the underlying intellectual property. For works like “Invincible” that were created after 1978, there are typically three ways that someone can become an owner or co-owner—by being a “joint author” of the work, by having a signed written work for hire agreement or by having a signed copyright assignment. (This is in contrast to pre-1978 works, which are subject to a more amorphous “instance and expense” test, as I discussed in my post on the Marvel copyright termination lawsuits.)

Let’s start with Crabtree’s joint authorship theory, which is actually more nuanced and complicated than it may first appear. The Copyright Act itself doesn’t provide any guidance on how to identify joint owners in a copyright other than to briefly define a “joint work.” A joint work is “a work prepared by two or more authors with the intention that their contributions be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.” This means that the individual contributions either aren’t meant to stand alone or that they achieve a greater overall effect when combined.

The Copyright Act’s definition of joint work focuses only on the co-creators’ intent to merge their individual contributions into a single unitary work. However, most courts (including the Second and Ninth Circuits) have implied the additional requirements that each author must contribute original expression that could on its own be separately copyrightable and that the authors also share the intent that each be co-owners of the copyright.

For example, in the case of Childress v. Taylor¸ the Second Circuit determined that Clarice Taylor wasn’t a joint owner because her contributions to a play about comedienne Moms Mabley—ideas and research—weren’t independently copyrightable and the script’s writer, Alice Childress, never intended to share ownership in the copyright. According to the court, “a useful test will be whether, in the absence of contractual agreements concerning listed authorship, each participant intended that all would be identified as co-authors.”

The Childress court was concerned that, without implying these additional requirements, the Copyright Act’s definition of “joint work” would encompass contributors like editors or research assistants who the parties would not normally expect to share copyright in the resulting work with the primary writer. The court also defended its approach as striking an appropriate balance between copyright and contract law. While the default rule favors a work’s dominant author, parties are free through appropriate written work for hire and assignment agreements to divide copyright ownership however they choose. Of course, as we see in the Crabtree case, parties don’t always properly document a relationship at the outset, which can create lots of problems later.

Did the Parties Intend that Crabtree Would Be a Joint Owner of “Invincible”?

As a practical matter, the test imposed by most courts sets a pretty high bar for joint ownership. The principal writers and illustrators of a comic book may qualify, but it’s much less clear that a colorist like Bill Crabtree would have an ownership stake.

There is some language in the Seventh Circuit’s Gaiman v. McFarlane case which notes that the content of a comic book is typically the joint work of four artists—the writer, the penciler who creates the art work, the inker who makes a black and white plate of the art work, and the colorist who colors it. Gaiman involved a dispute between Neil Gaiman and Todd McFarlane over co-authorship of characters from the “Spawn” series, and the court in that case actually rejected an independent copyrightability requirement for “mixed media” works like comic books. But the “Spawn” colorist wasn’t a party to the litigation, and the court didn’t go so far as to hold that he would qualify as a co-owner along with McFarlane and Gaiman.

The Ninth Circuit, which follows the majority view on joint authorship, has published model jury instructions containing a useful checklist of factors that a jury may consider in deciding joint authorship issues. Among them is whether each of the parties’ actions “showed they shared the intent to be co-authors when they were creating the work, for instance by publicly stating that the work was their shared project.”

A review of early issues of the “Invincible” comic books reveals that Bill Crabtree was one of three individuals credited on the title page, along with writer/letter Robert Kirkman and artist Cory Walker. But while Kirkman and Walker were also credited as “co-creators” of the work, Crabtree was only credited as the colorist. This suggests that at the time “Invincible” was first created, there wasn’t a joint intention to treat Crabtree as a co-author of the overall work.

The 2003 copyright notice at the bottom of the title page is in the name of Kirkman and Walker.

Curiously though, copyright registrations in the comic were filed solely in the name of Robert Kirkman, LLC back in 2003 as a work for hire.

Did the Parties Intend that Crabtree’s Contributions Would Be a Work for Hire?

The parties’ failure to properly document their relationship at the outset doesn’t just make it difficult for Crabtree to prove joint authorship. Kirkman’s copyright registrations list his entity as an “employer for hire,” but he didn’t have Crabtree sign the required written work for hire agreement prior to the work’s creation or registration. This will leave Kirkman’s lawyers to argue that the parties always intended Crabtree’s contributions to be rendered on a for-hire basis, and that the 2005 Certificate of Authorship was simply meant to document an agreement previously made. But of course Crabtree disputes the validity of the document and denies a work for hire relationship, and courts have previously rejected after-the-fact attempts to characterize a contribution as a work made for hire when one wasn’t actually intended at the time of creation.

The Bottom Line

Unfortunately, this all may leave the parties in a strange no man’s land in which Crabtree can’t clearly demonstrate that he’s a joint author while Kirkman can’t clearly demonstrate that he owns Crabtree’s contributions as a work made for hire. I expect the case to settle relatively quickly for this reason, much like a similar lawsuit filed against Kirkman in 2012 by Tony Moore, an early illustrator of “The Walking Dead” comic.

Of course, the moral of the story for both employers and creators is clear: get it in writing.

A copy of Crabtree’s new complaint follows. As always, let me know what you think in the comments below or on my social media accounts @copyrightlately!

View Fullscreen

1 comment

Great article, but I have one quibble. There are only two ways to become a joint owner of copyright, joint authorship and by assignment. The work made for hire provision of the Copyright Act only identifies who the author is for their particular contribution (the person who actually did the work or their employer/hiring party), not the type of authorship. One could have a mix of work made for hire and individual contributions to create a joint work, for example, if the writer and pencilist are employees but the inker and colorist are independent contractors.