With Dr. Seuss Enterprises deciding to no longer publish six books containing racially insensitive content, would it be fair use for others to do so?

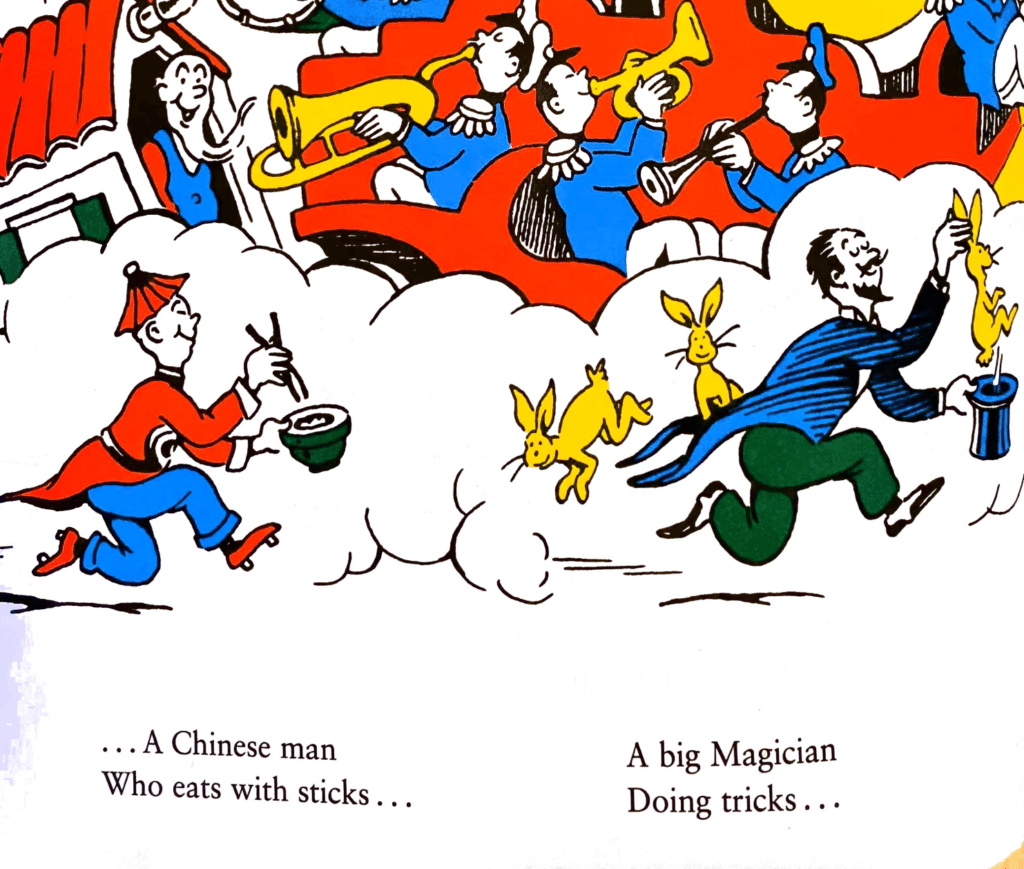

By now you’ve probably heard that Dr. Seuss Enterprises (DSE) has decided to stop publishing six Dr. Seuss books because they contain racially insensitive imagery and text.

To be clear—and contrary to some of the breathless headlines I’ve been reading—Dr. Seuss has not been “canceled.” DSE is a private company that owns the copyrights in the works of its namesake author, and it alone made the decision to voluntarily stop printing and licensing the books.

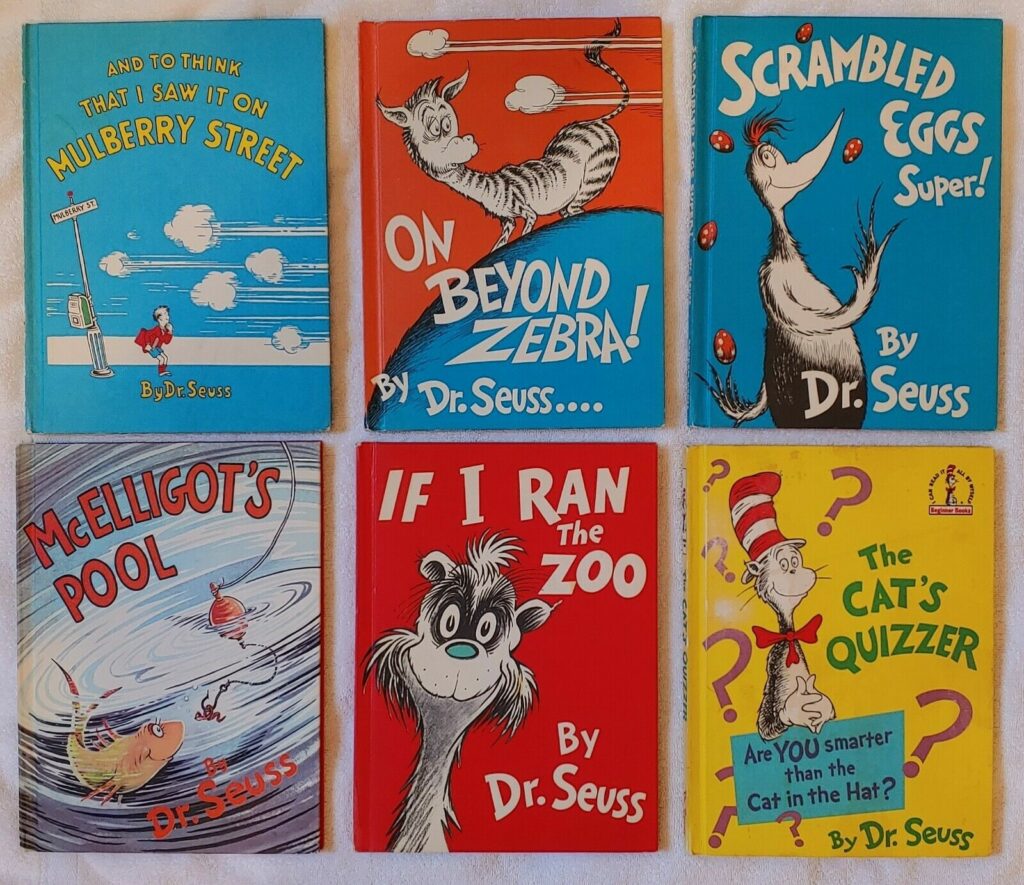

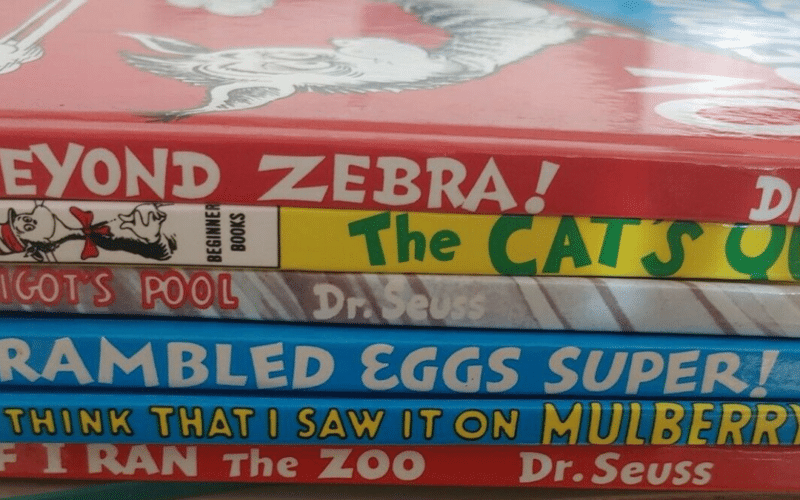

The affected works include “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” “If I Ran the Zoo,” “McElligot’s Pool,” “The Cat’s Quizzer,” “Scrambled Eggs Super!” and “On Beyond Zebra!”

These books certainly aren’t among Dr. Seuss’ most popular works. In the parlance of record albums, they’re more in the nature of “deep cuts.” (Think “Happiness is a Warm Gun” as opposed to “Hey Jude.”) But that hasn’t stopped some people from mourning the loss of books few of them actually bought, let alone read, when they had the chance.

Putting aside the cultural and political debates that DSE’s decision has caused, the sudden departure of these works from the market also raises an interesting copyright issue. Given that DSE has made the decision to stop publishing the books, would it constitute fair use if others were to now do so without permission?

Does a Right to Publish Mean There’s a Right to Unpublish?

Copyright owners generally get the first crack at publishing their works—or deciding not to publish them at all. If a work is unpublished, fair use is more difficult to establish, because an author is presumed to control the first public appearance of his or her expression. Whether the work at issue is a film intended for wide public distribution or a private letter never meant to see the light of day, a copyright owner gets to decide when, where, how—and if— to publish.

But what if the proverbial cat is already out of the hat? Having made the decision to publish a work, may the copyright owner decide to later “unpublish”—and to stop others from engaging in that work’s further dissemination?

In a recent paper entitled “Disappearing Content,” Stanford law professor Mark Lemley argued that copyright law’s fair use doctrine should be interpreted to allow third parties to make out-of-print works available, including in situations in which the works have “disappeared” because they’ve been deemed offensive in light of current norms.

Lemley’s position is that while the desire to remove racist or sexist material may be understandable, it doesn’t justify a retroactive “wiping” of the public record: “The public has a right to know what is out there even – perhaps especially – if the copyright owner now wants to pretend it never existed.”

While it’s one thing for the public to “know what is out there,” permitting the wholesale unauthorized copying and distribution of works that the copyright owner itself has recognized are culturally insensitive seems to be a bridge too far. As one district court remarked in rejecting an author’s attempt to publish an unauthorized sequel to “Catcher in the Rye,” copyright protection isn’t a “use-it-or-lose-it” proposition, and “the fact that any given author has decided not to exploit certain rights does not mean that others gain the right to exploit them.”

Preserving the Historical Record?

There isn’t a ton of recent precedent on the precise question of whether a desire to preserve an accurate historical record justifies copying that wouldn’t otherwise be considered transformative. In one notable case from back in 1939, the Second Circuit upheld an attempt by Adolf Hitler to block news reporter (and future U.S. Senator) Alan Cranston from publishing an “unexpurgated” translation of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf.”

Houghton Mifflin v. Stackpole Sons was an example of Hitler (through his publisher) using copyright as a tool of censorship, as the “official” version published by Hitler in the U.S. was heavily edited to conceal the full extent of his views and plans for world domination. Cranston thought it was important for Americans to understand the danger posed by Hitler by using his own unedited words, but Cranston’s actions resulted in the translation’s publisher being sued—successfully—for copyright infringement. (Note that the defendant in Stackpole Sons didn’t assert a fair use defense in the case, relying instead on a more technical argument regarding Hitler’s ability to assign his copyrights to the plaintiff.)

“Out-of-Print” as a Justification for Fair Use

Years later, the Senate Report issued in connection with what would become the 1976 Copyright Act noted that if a “work is ‘out of print’ and unavailable for purchase through normal channels, the user may have more justification for reproducing it than in the ordinary case.” Notwithstanding this language, I’m not aware of any cases since the Act was passed which have upheld a third party’s right to republish an out-of-print work in its entirely—especially in a situation where the copyright owner is actively looking to prevent that from happening.

That said, fair use tends to be a fairly malleable concept, especially when it comes to a court’s evaluation of the purpose of the defendant’s use. Even if someone doesn’t “transform” the work itself, there is an argument that merely making the work available as an accurate historical record serves a different purpose than the original. Note, however, that the Copyright Act already provides for specific exceptions which authorize libraries and archives to reproduce and distribute certain copyrighted works without permission on a limited basis for the purposes of preservation, replacement and research. My sense is that a court would likely find that these limited exceptions are sufficient to preserve the record, and that allowing a third party to essentially step in the the shoes of the original publisher would cross the line.

Protest Motives

What about republishing a work as a protest against the very fact that it has been unpublished in the first place? On March 2—the day DSE announced its decision to “retire” six Seuss books—someone registered the domain name BannedSeuss.com and reproduced twelve pages from “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.” Affixed to the top of the site is the message “Erasing books is insanity. Stand up for our common humanity,” with a link to a site called the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR), a group that criticizes what it refers to as “intolerant orthodoxy.”

“Banned Seuss” may itself fall within fair use, having reproduced only a dozen pages from “Mulberry.” Its justification for copying the whole book would be less compelling. (There’s also no small amount of irony with any attempt to use free speech as a basis to override DSE’s own right not to be compelled to speak.)

Profit Motives

The argument for publication would have even less force if the defendant were seeking to make a profit. Section 107 of the Copyright Act explicitly provides that whether a work is used for a commercial purpose as opposed to non-profit educational purposes needs to be considered in determining whether the purpose and character of the use is fair.

Frankly, I think it’s difficult to conceive of a situation in which a court would condone a competing publisher’s act of printing and selling “If I Ran the Zoo” or “McElligot’s Pool,” even if DSE couldn’t point to any particular market harm given its own decision not to publish. While U.S. copyright law is ostensibly concerned only with “economic rights” as opposed to “moral rights,” courts should—and likely would—defer to a copyright owner’s decision to protect an author’s legacy by keeping racially insensitive works off the market.

The First Sale Doctrine

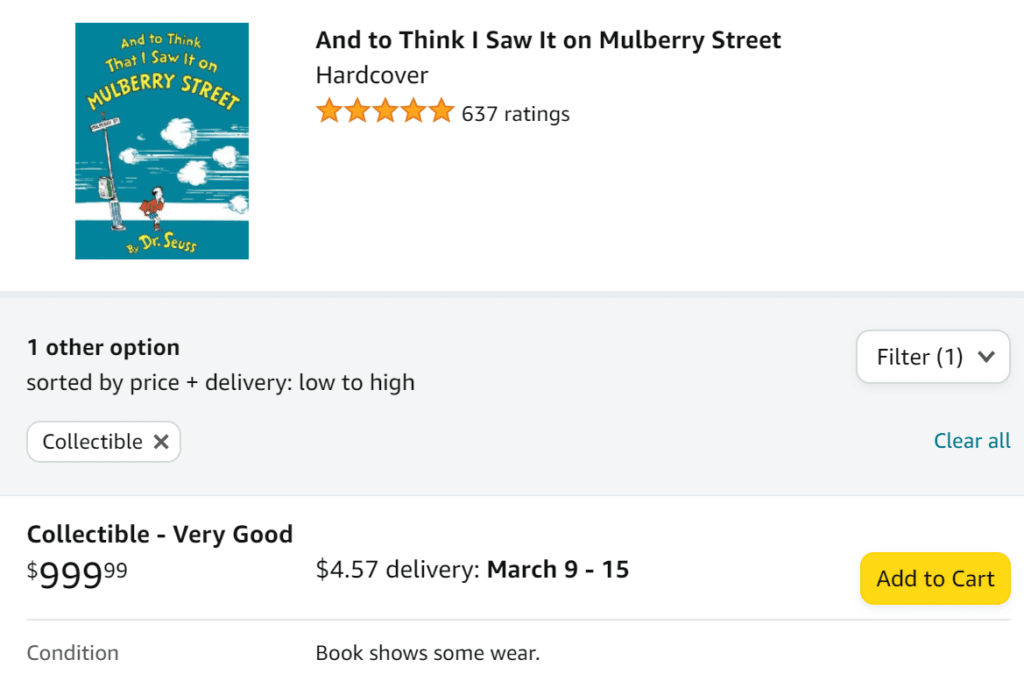

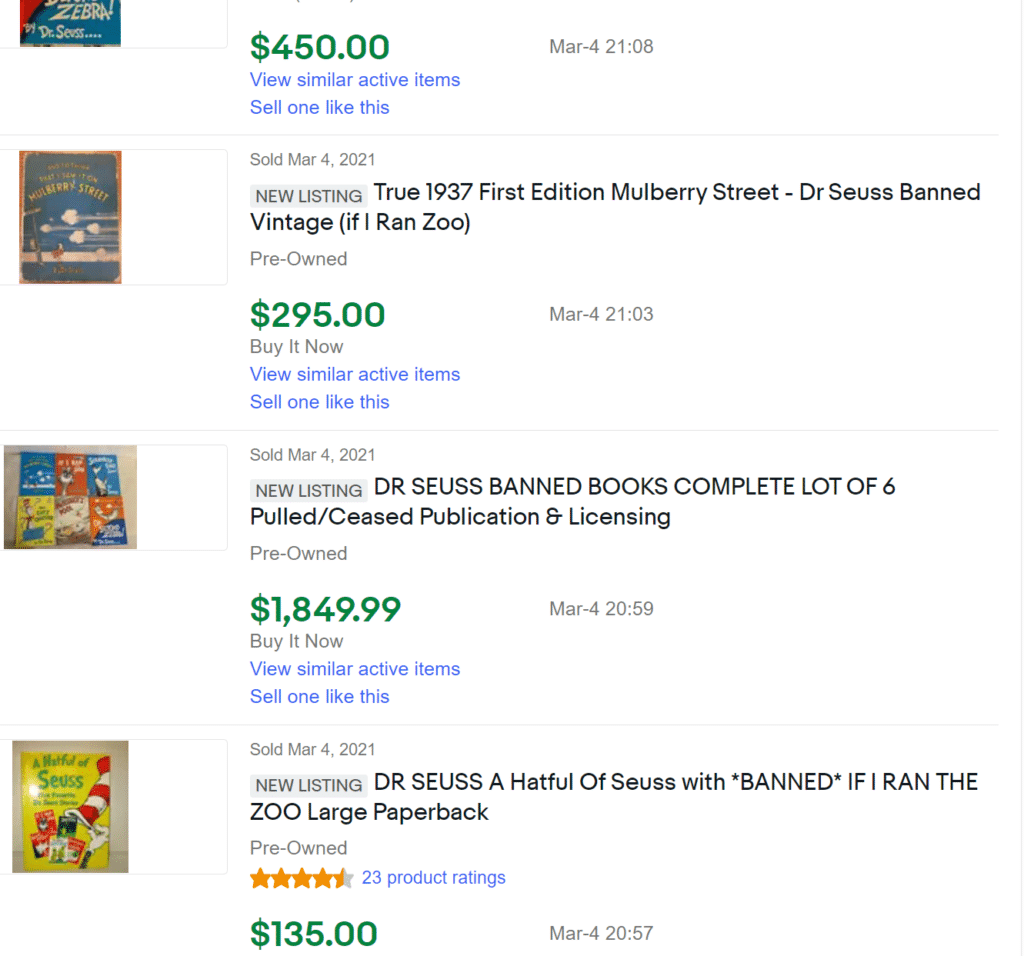

Of course, even if DSE can legally prevent new copies of Seuss works from being printed, it has no right to impound or otherwise restrict access to existing copies. Under the Copyright Act’s “first sale” doctrine, once the books have been subject to an authorized sale, the copyright owner isn’t permitted to control any future sale or distribution of those particular copies.

Given the sheer number of Seuss works that have been printed and sold over the years, I assumed there wouldn’t be a shortage for anyone who wants to buy a copy. However, it appears that a number of opportunistic sellers are attempting to cash on DSE’s decision to stop publishing the books at issue by jacking up the prices to many multiples of what they were selling for prior to DSE’s announcement.

On Amazon, where the Seuss books have been officially pulled by the site’s direct offerings, copies are still available from the site’s marketplace sellers.

The same is true on eBay, where as of yesterday the books had been selling at prices that only the wealthiest collectors of racist artifacts could afford.

As a postscript, I should note that while the copyright owner can’t legally prevent the owner of a lawful copy from reselling that copy, private marketplaces are well within their rights to prohibit the listing of items they deem to be offensive or otherwise unsuitable for sale. Indeed, as of Thursday, EBay has apparently decided to remove the Seuss books from its site, although a quick review reveals a number of listings still up at the time of this writing.

What’s Next?

It will be interesting to see whether any third parties will attempt to fill the void left by DSE’s decision to publish copies of the now out-of-print books. I expect that if they did, DSE would promptly begin legal action, given that the company isn’t exactly shy about filing copyright infringement lawsuits.

So what do you think? Should publishing new copies of an out-of-print book deemed by the copyright owner to be offensive qualify as fair use? Let me know in the comments below or on one of the Copyright Lately social media accounts.

2 comments

I always appreciate your timely analyses! Thanks!

Thanks so much for reading, and for taking the time to reach out – I really appreciate it!