AI-generated art isn’t perfect, but it’s become a viable option for license-free set decoration in motion pictures and other commercial productions. Here’s what you need to know.

Pandas, Monkeys and Clearance Culture

“Nobody cleared the panda.”

I was barely out of law school when a senior partner muttered those words as he handed me a scathing demand letter sent to one of the firm’s commercial director clients. The letter claimed that the director, an ad agency, and a popular theme park had all committed copyright infringement because a panda appeared in the background of their TV commercial.

It was actually a panda poster, which was tacked to a child’s bedroom wall. The poster was out of focus and only visible for a few seconds. It wasn’t a focal point of the commercial. But nobody involved in the production had asked for permission from the copyright owner to use her image in the scene, as the demand letter made sure to mention several times.

Arguably, permission wasn’t legally required given the poster’s fleeting and incidental appearance in the commercial, but nobody really wanted to find out. After some back-and-forth negotiation, our panda poster dispute was settled before a lawsuit was filed.

This was the late ’90s, and the entertainment industry was still reeling from a well-publicized copyright infringement case involving the movie 12 Monkeys. In that case, artist Lebeus Woods claimed that a torture device used in the Terry Gilliam film had been unlawfully copied from his drawing of a wall-mounted chair.

Even though the movie had already been in theaters for nearly a month, the judge issued a preliminary injunction preventing further exhibition of the film’s chair scene. This prompted a quick settlement which allowed the chair to remain in the picture. While folks who wanted to see Bruce Willis strapped to a torture device were happy, entertainment lawyers were anxious.

However, for every “Hey, that’s my church picnic quilt!” incident that results in a published court decision, there are dozens of others that are resolved quickly and quietly out of court. Fair use and de minimis defenses are often unreliable, and even if you have a solid case, defending copyright infringement lawsuits is an expensive proposition.

That’s why uncleared art and other props can be a set decorator’s worst nightmare. While decorative items often have thematic relevance to a story, they’re just as often used to avoid blank walls and unadorned coffee tables. When filmed, these items may be obscured, out of focus, and virtually unidentifiable. But if they appear on film without permission, even fleetingly, they could prompt a copyright infringement lawsuit.

The desire to avoid litigation at all costs has helped to create a “clearance culture” in which the standard operating procedure is for content creators to obtain a license (often at substantial expense) for every use of copyrighted material appearing in a production, regardless of whether permission is legally required.

AI-Generated Art to the Rescue?

Could AI-generated art offer an alternative? With tools like DALL·E 2 and Midjourney now able to produce unique, hyper-realistic images in a wide variety of different styles, the prospect of using these programs to create inexpensive set pieces and other artwork has suddenly become a viable option for all types of commercial productions.

Before exploring the copyright considerations involved in creating and using AI-generated art, I need to briefly raise a couple of points that aren’t the main subject of this post.

First, it’s an open question as to whether AI-generated art is itself eligible for copyright protection. The U.S. Copyright Office has taken the position that AI art created without an element of “human authorship” doesn’t qualify for protection and can’t be registered; that decision is now being challenged in federal court. So long as AI-generated art is simply used as a starting point for subsequent creative refinement by a human artist, the resulting work should be protected by copyright. But if you’re exploiting AI art generated without any human contributions, understand that you may have no legal recourse if others later copy that work. An image generation tool’s terms of service may further limit your rights contractually.

Second, and more importantly, there are a whole host of ethical and moral implications surrounding the use of AI-generated artwork, especially when the technology is used to produce outputs that are specifically designed to replicate the styles of living human artists without credit or compensation. It’s not my intent to minimize these issues; they just aren’t the focus of this article. I also recognize that there are lots of situations in which a set designer may want to include a specific copyrighted work that needs to be cleared. As I discuss below, using AI tools to create deliberate knockoffs carries major risks and it’s bad karma to boot.

That said, there are also plenty of times when a set designer’s goal is to dress a child’s bedroom with a panda poster, and pretty much any panda poster will do.

The often rough and imperfect nature of AI art creations makes them particularly good candidates for use on film sets in which the art will appear only fleetingly or out of focus. Likewise, AI art as a “stock image replacement” would certainly be a better alternative than simply right-click-saving a random image you find on the internet and using it without a license. Companies like Prepared Food Photos, Inc. have made an entire business out of suing individuals and companies for using relatively generic and utilitarian photos that could, in many instances, be easily replaced by AI-created art.

Is AI-Generated Art Copyright Infringement?

Of course, using AI-generated art as a license-free alternative for motion pictures and other commercial productions is only a viable option if the resulting artwork doesn’t itself infringe a preexisting copyrighted work. As TechnoLlama author Dr. Andrés Guadamuz has explained, the infringement issue needs to be examined at both the input phase and output phase of the generation process.

Inputs

AI tools are created by scraping hundreds of millions of images from the open internet and then training computer algorithms to recognize patterns in those images and their text-based captions. Eventually, the algorithms can start predicting which captions and images go together en route to generating entirely new images from new captions.

OpenAI, the research lab behind DALL·E, says that it trained that tool by scraping and analyzing more than 650 million captioned images, but its data is proprietary. However, Stability.AI, the company that created DALL·E competitor Stable Diffusion, has made the data used to train its program publicly available. Andy Baio, a technologist who analyzed 12 million of the 600 million images used to train Stable Diffusion, found that a large number of the images scraped were from websites like Pinterest and Fine Art America.

While the Ninth Circuit earlier this year reaffirmed that scraping publicly available data from internet sources doesn’t violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, no court has yet decided whether the ingestion phase of an AI training exercise constitutes fair use under U.S. copyright law.

In many ways, the process is like Google’s scanning of millions of books to create its Google Book Search tool. After years of litigation between Google and the Authors Guild, the Second Circuit held in 2015 that Google’s conduct in scanning the books and making short fragments or “snippets” available to end users qualified as fair use. Key to the court’s decision was the fact that Google scanned the books, not for their expressive content, but rather for use as a searchable research tool. Consistent with that purpose, Google’s search tool doesn’t give users substantial access to a book’s expressive content.

The Fourth Circuit reached a similar result in 2009, ruling that the scanning of student papers by the “Turnitin” plagiarism detection software in order to create plagiarism detection software was a fair use. Among other factors, “iParadigms’ use of these works was completely unrelated to expressive content and was instead aimed at detecting and discouraging plagiarism.”

Similarly, AI tools aren’t copying images so much to access their creative expression as to identify patterns in the images and captions. In addition, the original images scanned into those databases, unlike Google’s display of book snippets, are never shown to end users. This arguably makes the use of copyrighted works by OpenAI and Stability.AI even more transformative than Google Book Search.

Outputs

There are certainly interesting questions surrounding the potential liability companies behind AI tools could face for the copying that occurred at the input stage when the tools were first trained. But for the end user, the more important question is whether the output—the resulting image—is substantially similar to the protectable expression of any particular image used to train the dataset.

As I noted above, AI models are trained on hundreds of millions of image-text pairs. At the risk of over-simplifying (by a lot), once an algorithm is able to predict what an image should look like based on its caption, it can then be used to generate entirely new images from new captions.

It’s important to understand that the newest AI generation tools don’t simply cut and paste from any existing images. Instead, they use a technique called diffusion to generate entirely new images using the data on which they were trained.

OpenAI has admitted that its early AI-generative models would sometimes reproduce training images verbatim. “This behavior was undesirable, since we would like DALL·E 2 to create original, unique images by default and not just ‘stitch together’ pieces of existing images.” Recognizing that the verbatim reproduction of training images could also give rise to copyright issues, newer tools such as those used in DALL·E 2 were trained to recognize duplicates and avoid generating those images even when prompted to do so. According to OpenAI, “the new model never regurgitated a training image when given the exact prompt for the image from the training dataset.”

Assuming the truthfulness of OpenAI’s documentation, none of the outputs generated by DALL·E 2 should be identical to any other preexisting image. One way to verify this is to use a reverse image search app like Google Reverse Image Search or TinEye to compare the output to other images on the internet. More sophisticated tools like Google Lens can compare images (and individual objects within an image) to other images, and can then rank them based on their similarity and relevance to the objects in the original picture.

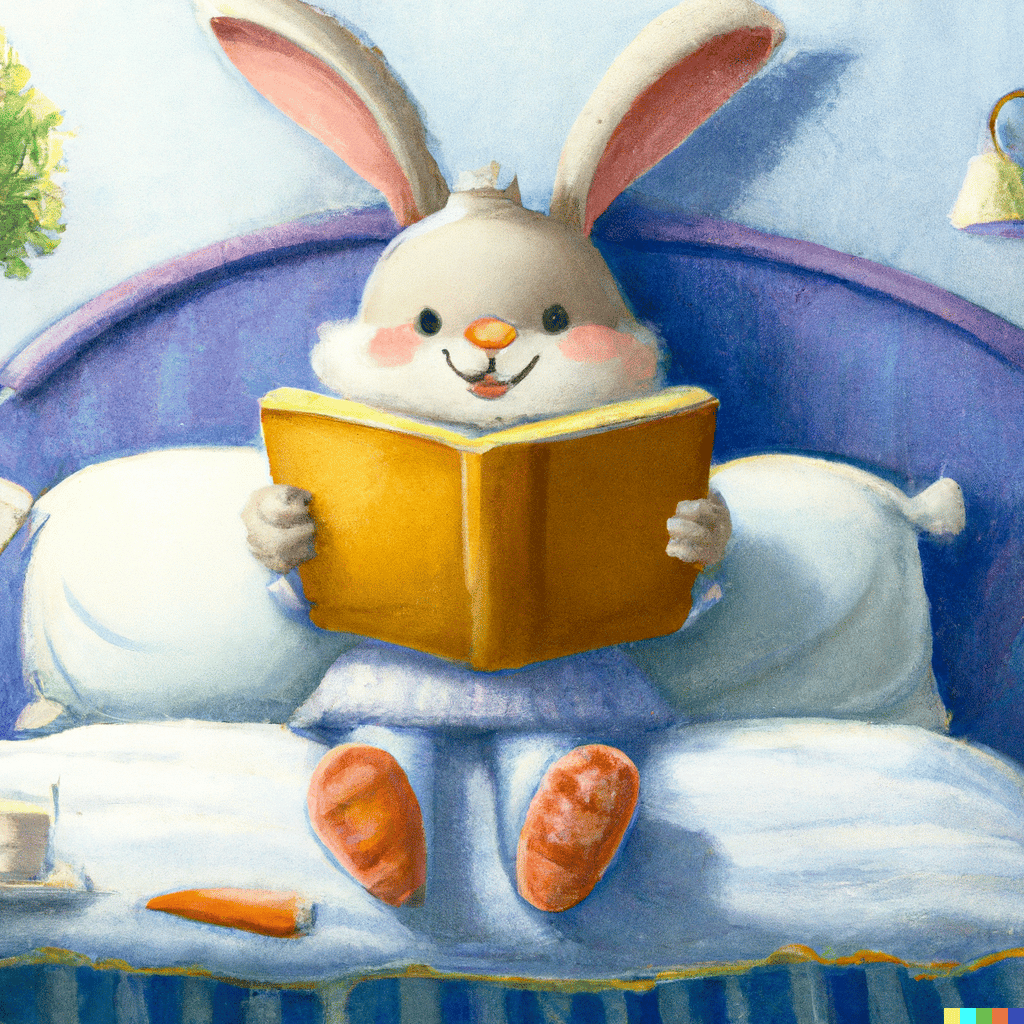

Below are three sample images I generated using DALL·E 2, none of which (at least according to Google’s Lens and Reverse Image Search tools) exists in a similar form on the internet:

Here are the results when I run my “whimsical painting of a cute bunny rabbit in pajamas reading a book in bed” image through the Google Lens tool. You can see that some of the preexisting images on the right-hand side capture the same (unprotectable) idea of a cartoon bunny reading a book, but none of them are substantially similar to the expression in my picture.

How to Avoid Infringement

As you might expect, there are a few important caveats.

First, even if an image produced by one of these AI tools isn’t substantially similar to any preexisting image, the generated output could still infringe one of the copyrighted elements found within a preexisting work. For example, prompts that specifically reference well-known or highly delineated characters are likely to produce infringing output. Here’s the result of my Stable Diffusion prompt “mickey mouse as a lawyer sitting at a desk with a bookcase of law books behind him”:

While this precise image has never existed before, there’s no question that I’d be infringing Disney’s copyright in the Mickey Mouse character if I were to use my picture in any sort of commercial context—as the reverse image search quickly shows:

This is not to say that every prompt referencing a copyrighted work will infringe, but you need to be careful. This may also be a good time to remind you that a lot of AI-generated art isn’t exactly ready for prime time:

Second, some AI tools, like Midjourney, another DALL·E competitor, allow users to upload their own reference images in addition to descriptive prompts that can help point the program toward a desired output. It probably goes without saying, but if you’re looking to avoid infringing a preexisting image or copyrighted work, you shouldn’t use one as a reference image. Here are the variations that Midjourney came up with when I uploaded my “bunny reading a book in bed” reference image. While they have slightly different features, they’re all substantially similar to my original.

Third, while artistic styles are not protectable in and of themselves, if you create art specifically designed to replicate the style of a preexisting work, the output will necessarily share some degree of similarity to the original. This is even more likely if you upload a reference image to help guide the AI tool. Prompts that refer to the style of a particular living artist could result in a legal claim, depending upon how similar the work is to one of that artist’s originals. Think of it as the “Blurred Lines” case, but with images rather than music.

Case in point: You may recall the scene in Titanic when Rose shows off a collection of artwork she purchased in Europe. When she’s asked who created one of the pieces, Rose responds, “Oh, something Picasso.” The painting Rose is holding is similar to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, but it’s not an actual reproduction. That didn’t stop the Artists Rights Society from complaining on behalf of the Picasso estate.

Is it infringing? Perhaps not, but do you really want to find out? The point is to stay far enough away from the line that you won’t trigger even a nuisance claim. Since our goal is to avoid copyright infringement, it’s best to use prompts that don’t reference any particular copyrighted work. Also, if you’re going to replicate art in the style of a particular artist and want to be totally safe from a copyright perspective, pick an artist who’s been dead for at least 70 years. Better yet, use generic descriptors in your prompts.

Some Tips for Avoiding Copyright Infringement When Using AI-Generated Art

If you’ve made it this far, here are some takeaway points:

- Make sure your AI tool’s terms of service allow for the commercial use of output images.

- Use relatively generic prompts for style descriptors—e.g., steampunk, bauhaus, claymation.

- Check outputs using reverse image search tools.

- Save the prompt used to generate each image you create in the image file’s metadata or filename for later reference.

- Don’t include references to preexisting copyrighted works or characters in your prompts.

- Don’t upload preexisting reference images unless you own the copyright in those images.

AI-generated art is a controversial topic, and as always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. You can post a note in the comments section below or @copyrightlately on social media. I also want to give a shout-out and thank you to my IP colleague Peter Jackson for helping to educate me on some of the tech behind the AI tools discussed in this post.

12 comments

Great article explaining so many of the nuances around AI generated Art 🎨… thank you for making it clear and simple!

Thanks so much for reading!

First, hello Aaron and congratulations on a this excellent website and helpful article, which I just discovered while surfing. You may recall our working on some matters when I was at Warner Bros. I’m now retired and I welcome your website (and your always thoughtful writing) as a way of keeping up with copyright issues. Never a dull moment!

Best wishes.

Hi Jeremy – it’s so great to hear from you! I hope you’re enjoying retirement, and am glad you find the site useful. Let me know if you have any suggestions for future articles or features.

Best Regards,

Aaron

Facial likeness may be a huge issue. B and C list celebs are in Getty Images, which was used to train Stable Diffusion. There will be a lot of pictures created that incidentally look like a minor celebrity, especially if that celeb is a beautiful woman (MidJourney leans heavily towards making beautiful women / models). The creator may have no idea who the celeb is but they may accidentally create that person’s likeness.

I had been making collages from public domain images (mostly 19th century chromolithographs), my assumption being that those new works would be owned by me- they were substantially new and different. I then started using ai to make similar source material and then put different images together . I wonder if the notion of collaged pieces from public domain material is useful in the ai copyright discussion.

On a more diffuse note I’d say that even my unaltered ai generated images have an element of me in them, probably from my prompts, my development of those prompts based on results, and my selection of which pieces I think is successful. (I’m a photography and some of this is similar to photographic methods.

The magic, (say the ghost in the machine), is that these images are also other than me- they surprise me. I find them to be dreamlike in the sense that one has many dreams which it would be hard to make up.

Your writing has a poetic quality that makes it a joy to read.

is it plagiarism to use ai art for my dnd characters not commercial

Would descriptions like anime style, pop art style or sticker style be considered generic?

yep

When ART is dead you will know AI killed it.

We will live in a drone like society of morons.

We are headed there and AI drug dealers lead the way.

A country and world of shit bag content criminals.

Why not though. The ex president of Harvard is one of them. Why not. It will net you a million dollar job. When there is no longer anything to skim…

What will the shitbags do?

How bugs feel: When I was about 5/6 my mom and stepdad bought my sister and I bikes for Easter. After church they were like “do you wanna learn how to ride them?” And I was like??? Duh?? I had finally gotten the hang of it and I was riding around the circle showing off, and my mom was like “say cheese” so I look over at her for a second and I FUCKING RAM INTO A CAR AT FULL SPEED. A parked car that I didn’t even see, like at all, so I just rammed into this car and I fell off my bike and I was crying and all I could think about was “this must be how bugs feel” like they’re flying around living life and then SPLAT. Looking back that was my first existential crisi. More stories here https://u.to/62ikIA