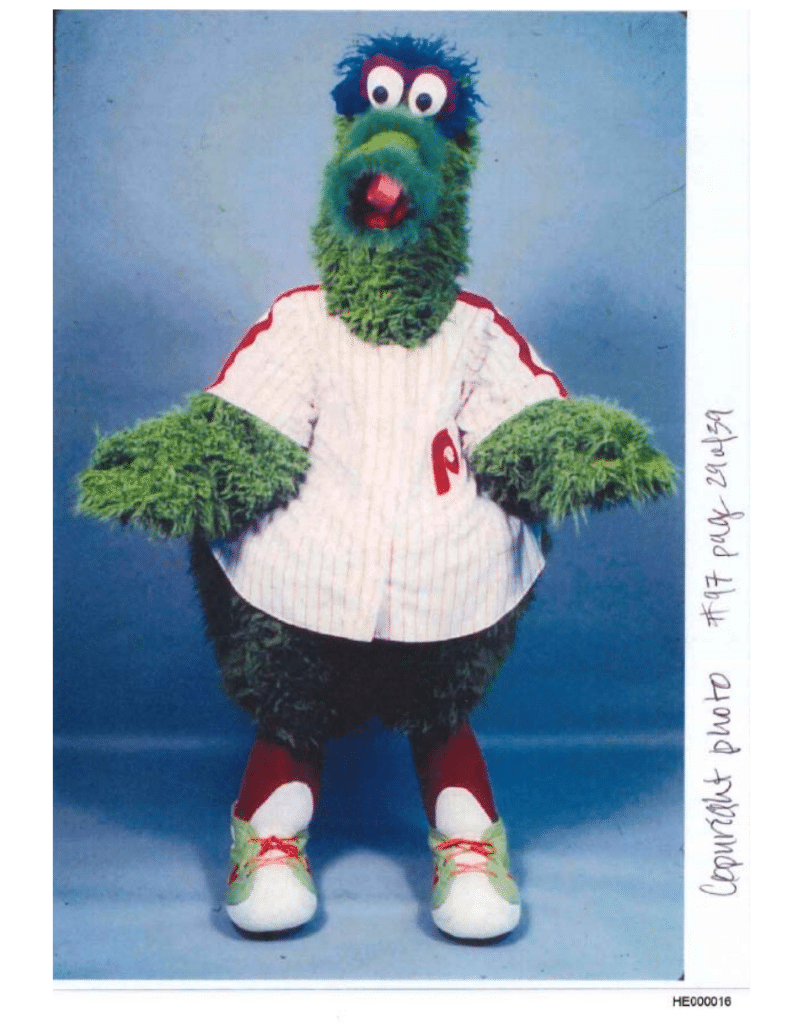

Can the Copyright Act’s “derivative works exception” help the Phillies blunt the effect of a copyright termination notice from their mascot’s designer?

Is it just me, or do Philadelphia sports mascots seem to get caught up in more than their fair share of legal controversies? Last year, Gritty was investigated for allegedly punching a 13-year old hockey fan at a Philadelphia Flyers photo shoot. Now, baseball’s iconic Phillie Phanatic is locked in a bruising copyright battle involving an attempt by its original creators to terminate a 1984 agreement which transferred copyright in the snout-nosed mascot to the Philadelphia Phillies.

On December 10, the Phillies filed a motion for summary judgment in the case, which raises a number of interesting issues involving statutory copyright termination. That’s a provision of the Copyright Act that allows authors and their heirs to terminate copyright assignments and licenses after 35 years, thereby recapturing the assigned rights “notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.”

The Phillie Phanatic and the 1984 Assignment

According to the motion, in 1978 the Phillies entered into an agreement with creative design firm Harrison/Erickson (H/E) to design and construct a costume for the team in exchange for a payment of $3,900. The Phillie Phanatic quickly became popular with the team’s fans. However, the original license agreement between the parties didn’t include a transfer of H/E’s copyright interests in the mascot. So in 1984, the parties renegotiated their prior deal, and H/E was paid $215,000 for assigning all of its rights in the Phanatic to the team.

Harrison/Erickson Terminate the 1984 Assignment

Over the years, the Phillie Phanatic has become one of the most well-known and popular mascots in sports, and the Phillies have created and sold hundreds of promotional items and products based on the character. Presumably wanting to capture some of this increased value, H/E’s attorneys served a termination notice under section 203(a) of the Copyright Act in 2018, which purported to terminate the 1984 assignment effective June 15, 2020.

H/E’s termination notice prompted the Phillies to do two things. First, the team filed a lawsuit against H/E in August 2019, seeking, among other things, a declaratory judgment that the termination notice was not effective.

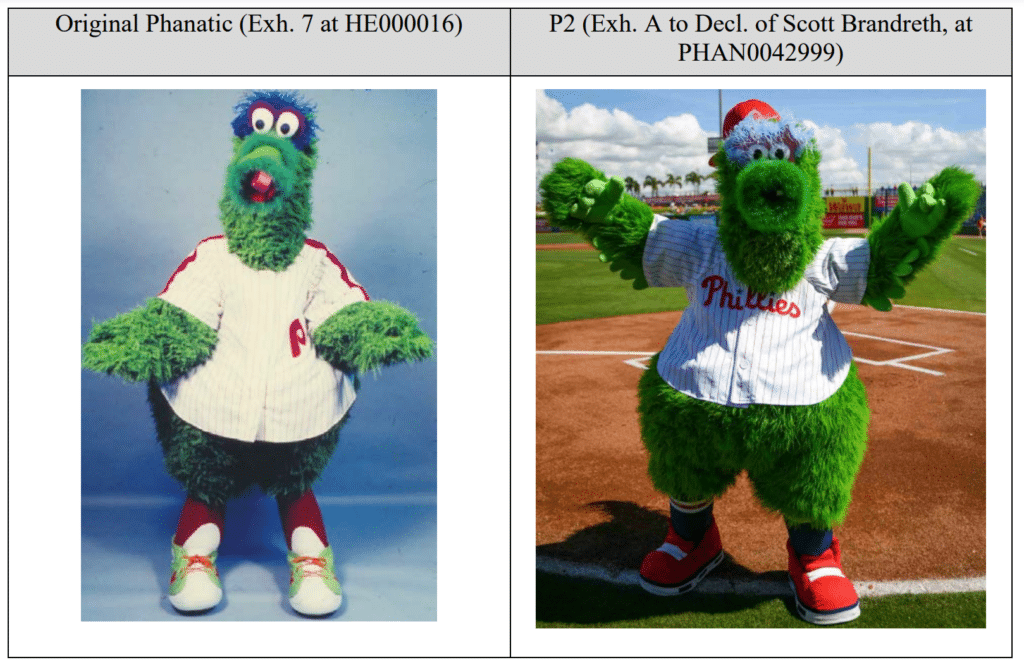

Second, The Phillies made a few “modifications” to the Phanatic prior to the start of the 2020 baseball season.

The New Phillie Phanatic

Among other things, the “new” Phanatic features a squatter, cylindrical snout, bushier eyebrows, powder-blue tail feathers, pink star-shaped eyelashes and rounder eyes. Apparently the new features are designed to give the character a more bird-like impression. (To be honest, I had always assumed the Phanatic was some kind of an aardvark, although I’ve also heard it described as the love child of Oscar the Grouch and Q*Bert.)

The team’s modifications didn’t seem to go over very well with Phillies fans, who protested the change on social media. John Oliver even devoted a segment of his HBO show to the controversy. “The point is the old Phanatic was perfect just the way he was,” Oliver quipped. “Look at him, he’s a ‘Sesame Place 10.’ Now, he’s a ‘Times Square 6′ at best.”

While not overtly publicized, the changes to the Phillies mascot were driven primarily by the team’s legal strategy—an effort to continue using the character in the event H/E’s copyright termination efforts proved successful.

The Derivative Works Exception to Copyright Termination

Specifically, the Phillies’ redesign was intended to take advantage of section 203’s so-called “derivative works exception,” which permits the owner of a derivative work prepared before termination to continue using that new work even after termination. The derivative works exception is what allows studios to continue to exploit movies based on underlying books and plays even if the underlying rights in those works are later recaptured following statutory termination.

In their new motion for summary judgment, the Phillies ask the court to rule as a matter of law that, even if H/E’s copyright termination notice is effective, the team is entitled to continue to utilize the new derivative version of the character going forward.

The derivative works exception provides:

A derivative work prepared under authority of the grant before its termination may continue to be utilized under the terms of the grant after its termination, but this privilege does not extend to the preparation after the termination of other derivative works based upon the copyrighted work covered by the terminated grant.

17 U.S.C. § 203(b)(1)

In a pre-motion letter to the judge, H/E blasted what it says is an “insidious attempt” by the Phillies to supplant H/E’s copyrights and an “abuse” of the derivative works exception: “The Phillies created and publicly introduced a knock-off Phanatic that the team concocted with its lawyers during the litigation, which looks nearly identical to H/E’s Phanatic, albeit with extremely minimal alterations, most of which are barely even noticeable.”

How to Apply the Derivative Works Exception

Having litigated a number of character-related copyright termination matters over the years, I can say that the derivative works exception presents some complicated issues when it comes to parsing the rights of the terminating and terminated parties. This is especially true with fictional characters. These works tend to evolve over time, especially when they’re expressed in graphic form.

While an author (or the author’s heirs) may be able to recapture rights in the original character, the work that’s ultimately recaptured right may be relatively worthless if it no longer represents the version familiar to the public. At best, the terminating party will have the right to “block” the terminated party from fully exercising its rights, which can lead to a re-negotiation between the parties.

Another complication stems from the fact that there’s some inherent tension between the right to create new derivative works (which belongs to the owner of the recaptured copyright) and the right to continue to utilize works prepared under authority of the grant before its termination (which belongs to the original grantee).

The law has generally been interpreted to permit the terminated copyright owner to engage in activities that are necessary to effectuate its rights to “continue to utilize” derivative works after termination, so long as they don’t alter the fundamental nature of the work itself.

So, for example, a studio could continue to make additional copies of a film that it produced while the grant was in effect, as well as to exploit that film in different formats that don’t transform the essential character of the work (e.g., broadcast television, Blu-ray, streaming). On the other hand, the studio couldn’t remake the original film post-termination, as that would constitute a new derivative work based on the underlying terminated work.

While case law in this area is relatively sparse, there are some general principles that the court (or ultimately a jury) will need to apply when deciding the scope of the Phillies’ future rights in the Phanatic.

What’s a Derivative Work, Anyway?

One of the issues to be decided is whether the new version of the Phillies Phanatic constitutes a derivative work in the first place. Under the Copyright Act, “derivative work” is defined as a work “based upon one or more preexisting works” that “recast[s], transform[s], or adapt[s]” a preexisting work. “A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a ‘derivative work.’”

H/E argues that the changes made to the Phillies’ mascot are barely noticeable and that anyone viewing the new version is going to still recognize it as the Phanatic. Of course, this may often be the case with derivative works, which are by definition substantially similar to the original. Indeed, a work is only going to be considered a derivative work in the first place if it would be treated as an infringing work in the absence of a right to exploit.

While minor differences to an original work won’t qualify as independently copyrightable derivative works, the standards aren’t exceedingly high. The degree of originality needed to qualify for protection has been described by courts as “modest” and “minimal,” although the author of the new work does need to contribute more than “merely trivial” variations to the original.

This all said, the significance of the Phillies’ changes to the Phanatic, and the extent to which they “recast” the original, aren’t particularly clear cut. I suspect the court will find that there are disputed factual issues that can’t be determined on a motion for summary judgment and which need to be decided by a jury.

The Right of Continued Utilization

Assuming that H/E’s termination notice is valid, and that the new version of the Phanatic does constitute a derivative work, another issue that will need to be decided is the extent to which the work can be utilized in new media or on new products. The team could make copies of the work as necessary to exercise its right to continue to use pre-termination derivative works. On the other hand, it wouldn’t be able to create new adaptations that would qualify as independently copyrightable derivative works.

Ironically, this means that for purposes of the continued utilization analysis, the Phillies need to show that any post-termination exploitation does not rise to the level of a derivative work—a 180-degree reversal from its argument as to pre-termination works.

The majority of courts (including in the Second and Ninth Circuits) have held that variations to a character that result from creating a three dimensional version of a two dimensional character (including changes in the proportion of textures, facial features and facial expressions) are insufficient to render the 3D versions eligible as derivative works.

These cases suggest that the Phillies will be allowed to make post-termination modifications to the Phanatic that are dictated by the function or medium of the use. (To be clear, this assumes that the pre-termination “new” Phanatic is an independently protectable derivative work in the first place).

Check out the Phillies’ motion for summary judgment below. I’ll be keeping my eye on this case to see how it plays out in court. In the meantime, if you have any comments or questions about the derivative works exception or copyright termination in general, let me know in the comments!

UPDATE—August 10, 2021 —In a 91-page report and recommendation, a magistrate judge finds that the new version of the Philadelphia Phillies’ mascot falls within the “derivative works exception” to copyright termination. But questions still remain. Check it out here.

View Fullscreen