Donald Trump argues that a campaign ad featuring the Eddy Grant song “Electric Avenue” is protected by fair use. Here’s why he’s wrong.

UPDATE—October 23, 2023—The Eddy Grant/Donald Trump lawsuit is still going strong three years after it was filed. In a new post, I explain how Trump is defending the case while trying to keep his deposition testimony permanently under seal.

If you were to make a list of all the things President Trump has called “unfair” over the past two weeks, it would be nearly as long as the list of people jockeying for presidential pardons as his term draws to a close. From an election he claims was rigged to news media he believes has been overly-focused on COVID, Trump has been airing more grievances than Frank Costanza at Festivus dinner.

But Trump is singing a different tune when it comes to a copyright infringement lawsuit brought against him and his presidential campaign by musician Eddy Grant. In a motion to dismiss filed last week in the Southern District of New York, Trump claims a campaign ad deriding Joe Biden makes “fair use” of Grant’s 1983 hit “Electric Avenue.”

A couple of months ago, I wrote about a copyright infringement complaint that another musician, Neil Young, filed against the Trump Campaign. That lawsuit concerns Trump’s use of two of Young’s songs at a live campaign rally, implicating the public performance rights typically licensed by organizations like ASCAP and BMI. Grant’s claim concerns a more garden-variety use, a 40-second clip of “Electric Avenue” as the soundtrack to a recorded political ad. While the Trump Campaign didn’t create the ad, Trump did retweet a copy of it back in August. And yes, as Trump himself foreshadowed in a July interview with Dave Portnoy, “it’s the retweets that get you in trouble.“

Eddy Grant, Jackson Browne and David Byrne Walk into a Bar…

You remember “Electric Avenue,” right? It was a song made famous in 1983 through a combination of its catchy chorus and a veritable blitzkrieg of MTV video airplay. The song itself is about the 1981 Brixton riot in South London, an area plagued by socio-economic problems and extreme poverty. Violence in the streets, hunger among the residents. In other words, the perfect backdrop for a campaign ad showing… Joe Biden pushing a handcar over random audio snippets of Biden talking about his hairy legs?

Putting aside whatever drugs the guy who created this ad may or may not have been on when he decided that “Electric Avenue” was the only thing preventing him from finishing this masterpiece, the song’s presence in the video makes no more sense than the video’s reference to what Biden “learned about roaches.”

Grant’s case reminds me a bit of two other previous lawsuits involving prominent Republican candidates. In 2008, singer-songwriter Jackson Browne sued then-presidential candidate John McCain and the Republican National Committee over the use of Browne’s song “Running on Empty” in an ad criticizing his opponent Barack Obama’s energy policies. A couple of years later, David Byrne sued former Florida governor Charlie Crist for using Talking Heads’ “Road to Nowhere” in an ad suggesting that his Senate campaign challenger Marco Rubio didn’t have a solid plan.

After McCain’s early attempt to dismiss Browne’s complaint on fair use grounds proved unsuccessful, the parties later resolved the case with an apology from McCain. While McCain noted that he “had no knowledge of or involvement in” the campaign video, he did “not support or condone” any actions that were “inconsistent with artists’ rights or the various legal protections afforded to intellectual property.”

Charlie Crist’s subsequent recorded apology to David Byrne was a bit more cringe-inducing, and was posted on YouTube for posterity:

But let’s face it: If we’ve learned anything about Donald Trump in the past four years, it’s that he doesn’t apologize for anything. This means that the “Electric Avenue” litigation will have to be resolved by Southern District of New York Judge Koeltl, to whom the case has been assigned.

Trump’s Motion to Dismiss

As an initial matter, I should note that it’s relatively difficult for a defendant to achieve a favorable fair use ruling on a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6). It does happen sometimes, as recently illustrated by a court’s decision in favor of United Sports Publications. The defendant embedded an Instagram post originally published by tennis player Caroline Wozniacki, and the court found that because the defendant commented on the post itself, the fair use defense applied.

That said, I don’t think Trump’s going to be as fortunate. His motion to dismiss does attempt to check all the traditional boxes that courts use to examine fair use: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use on the market for the original. Let’s break them down.

The Purpose and Character of the Use

This first factor is where most of the action is nowadays. And to be clear, I’m only talking about copyright law, just in case you’ve decided to compare fair use to whatever booze-soaked debauchery passes for a Thursday night in your neck of the woods.

Transformative Nature of the New Use

Courts here are basically looking at the extent to which the defendant has used the plaintiff’s work in a new or different manner or for a different purpose than the original, altering it with a “new expression, meaning or message.”

Trump’s position on this factor essentially comes down to arguing that the original purpose of “Electric Avenue” was as a standalone pop song, which was then “transformed” (by being copied, verbatim) onto the soundtrack of a comedic video designed to mock Joe Biden. According to Trump’s lawyers, hard-hitting lyrics like “now in the streets there is violence” stand in “stark juxtaposition to the comedic nature of the animated caricature of Former VP Biden, squatting and pumping a handcar with a sign that says, ‘Your Hair Smells Terrific.’”

Of course, by this logic, any time a song is used to promote an unrelated product or service, it would be transformative. For example, imagine the psychedelic dreampop of Glass Animals’ “Tangerine” being used to sell (not fruit, too easy)—Cool Ranch Doritos. Now that’s a stark juxtaposition.

But it’s not fair use.

Note that in the McCain case, the defendants argued that the use of “Running on Empty” was transformative because a “mood evoking soft rock composition about the lifestyle of a musician” was turned into “a biting commentary on aspects of a Presidential candidate’s proposed energy plan.” While the judge in McCain declined to decide fair use on a motion to dismiss, other cases have certainly recognized that defendants have some latitude in the new meaning or message they might create by using the original. That’s why McCain’s lawyers made the argument they did.

But here, Trump doesn’t even attempt to tie the lyrics of “Electric Avenue” to any particular message about Joe Biden. The ad at issue doesn’t comment on the original song, or on the artist. It doesn’t even use the original to make a comment on something about the campaign. Trump’s lawyers even concede in their motion that “Biden’s voice overpowers the volume of the music, making it difficult to hear the lyrics of Plaintiffs’ song,” an argument that undercuts any argument that “Electric Avenue” was transformed in any appreciable way.

In other words, you could substitute Grant’s music for any other song with comparable beats-per-minute and you’d have a similar final product and the same legal argument Trump’s making here—which is to say, not a very good one.

Commercial vs. Noncommercial Purpose

Now, it is true that when courts evaluate the first fair use factor they look, not only at the degree to which the new work is transformative of the original, but also whether the original work has been used for a commercial or noncommercial purpose. It’s also true that most cases considering campaign ads (though not all of them) have characterized such ads as noncommercial political speech. However, this analysis is a small part of the overall first factor calculus, and rarely drives the ultimate outcome of even this factor, let alone the entire fair use analysis.

Additional Considerations

More typically, my sense is that courts approach fair use by examining the overall gestalt of a defendant’s work and then (whether subconsciously or intentionally) viewing the individual fair use factors through that prism. The factors that support the ultimate conclusion become more important than the ones that don’t. This is why litigants often will try to remind judges of other cases they’ve decided and argue that they should view the case at issue through the same lens.

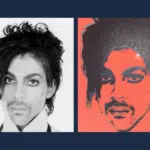

If my theory is correct, it’s no surprise that Trump’s lawyers repeatedly cite Judge Koeltl’s opinion in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith in their motion, even though that case is currently up on appeal to the Second Circuit. In the Warhol case, Judge Koeltl took a pretty liberal view of fair use, leaving some people wondering how much the court may have been influenced by the fact that the art at issue was by Andy Warhol. In its opinion, the court discussed how the plaintiff’s original photographs depicted pop star Prince as a “vulnerable human being,” while Warhol’s art transformed Prince into an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Note, however, that even in this case, the fair use determination was made on summary judgment, following discovery, not on a motion to dismiss.

The Nature of the Song

The middle two factors have pretty much become the Rodney Dangerfield of the fair use world. They typically get short shrift from courts and litigants alike, and courts will find that these factors weigh in favor of the plaintiff, but still find for defendants, and vice versa. They really don’t end up mattering very much. That said, they both favor Eddy Grant in this case.

Discussing the second “nature of the work” factor, Trump concedes that “Electric Avenue” is a “creative work” (as opposed to, say, a factual or historical work). However, he argues, the song “was published in 1983 … and it remains, more than 37 years later, available to the public. This weighs in favor of fair use.”

While the phrasing is odd, I don’t think Trump’s lawyers actually meant to suggest that Eddy Grant has already milked whatever useful life he’s going to get from his song and that it’s free for all to use during the next 58 years that it still enjoys copyright protection in the U.S. Rather, I’m assuming Trump is making an oblique reference to the fact that the campaign ad didn’t usurp Grant’s right to decide when (and if) to publish his work for the first time.

It also appears that “Electric Avenue” has been used in at least one other commercial—during the 2015 Super Bowl no less. A portion of the song was used in BMW’s ad for its i3 electric vehicle. However, as discussed below, while that doesn’t affect the song’s value as a “creative work” under the second fair use factor, it should support Grant’s argument that there’s a licensing market for the song per the fourth factor.

The Amount and Substantiality of the Use

Trump’s argument on the third factor doesn’t move the ball in his direction either.

Here, Trump contends that the campaign ad “uses enough of the song to introduce the animated caricature of Former VP Biden, to support his overlayed speech about ‘hairy legs,’ and to end the video with the phrase ‘BIDEN TRAIN’ falling off the screen.” Translation: “the amount of the song we included was directly related to the amount of nutty random footage we needed to overlay.”

Aside from simply underscoring that the song has nothing to do with the commercial, it’s a disingenuous argument. The ad uses 40 seconds of Grant’s song, including the most recognizable chorus parts. Most television commercials are only 30 seconds long. And I’m sure that if the creators had 10 more seconds of Joe Biden talking about his hairy legs in their video, they’d have used 10 more seconds of “Electric Avenue.” This one also weighs in favor of Grant, to the extent it matters at all.

Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market for or Value of the Copyrighted Work

The fourth fair use factor still does get some respect, although frankly not as much as it used to before transformative use muscled its way to the top spot. Here, Trump argues that the campaign video isn’t a substitute for the original song—essentially no one wanting to listen to “Electric Avenue” would turn to the commercial instead.

“It is utterly implausible that fans of Mr. Grant’s music, or pop music listeners in general, would opt to acquire the Animation in preference to the Song, in order to watch the Animation and thereby to hear the warped snippet of the Song accompanied Former VP Biden’s voiceover.”

President Trump’s argument on the fourth fair use factor (effect on market value), from Grant v. Trump Motion to Dismiss

However, entirely missing from Trump’s argument is any discussion of the licensing market for Grant’s work. Will the fact that “Electric Avenue” has now already been used in a viral Trump ad prevent Grant from licensing it to other political candidates, or even to more traditional commercial advertisers? If not, would the licensing price nevertheless diminish because the song’s been associated with Trump? Maybe yes, maybe no. Expect Grant’s lawyers to argue that they need discovery on these issues and that the case can’t be dismissed right out of the gate.

In these types of cases, courts will often look to expert testimony to determine whether a licensing market has been affected by the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s work. For example, in 2010’s Henley v. DeVore, the court agreed with an expert for the plaintiff (The Eagles’ Don Henley) who testified that licensees and advertisers don’t like to use songs that are already associated with a particular product or cause. Here, you have two potential strikes against the market for “Electric Avenue”—the fact that the song has now already been used in an ad, as well as the fact that it was associated with a politician who’s a lightning rod for many Americans.

What’s Next

Eddy Grant’s lawyers should be filing opposition papers to Donald Trump’s motion to dismiss soon. I’ll give you the updates here. In the meantime, below is Trump’s original filing if you’d like to take a look. As always, let me know what you think!

UPDATE—September 28, 2021—SDNY denies Donald Trump’s motion to dismiss in Eddy Grant “Electric Avenue” copyright infringement case. Each fair use factor weighs in the plaintiff’s favor at this stage. Trump can try again on summary judgment but it’s not looking good for him. Full ruling here.

View Fullscreen