Composer Jay Livingston’s granddaughter is suing her mother for exercising copyright termination rights in “Que Sera, Sera” and other popular songs.

A new complaint over song royalties is a good reminder that the best-laid plans of mice and musicians can go awry if their lawyers don’t properly understand copyright termination.

The dispute pits Tammy Livingston, the granddaughter of Academy Award-winning composer Jay Livingston, against Travilyn Livingston and her publishing company, Jay Livingston Music. Tammy’s complaint (read here) refers to defendant Travilyn as her “biological mother,” which tells you all you need to know about the state of their familial relationship.

Livingston v. Jay Livingston Music, Inc.

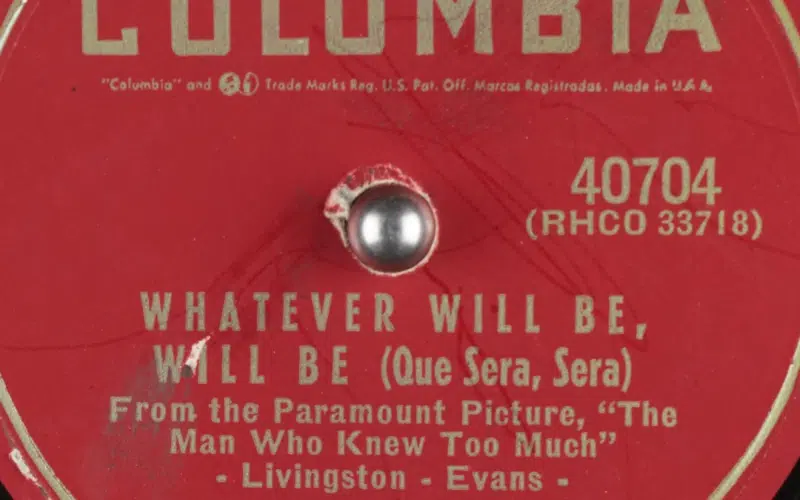

Jay Livingston, who was Travilyn’s father, co-wrote some of the most famous compositions in American history with his partner Ray Evans. Their best-known work is “Whatever Will Be, Will Be (Que Sera, Sera),” which was sung by Doris Day in the 1956 Alfred Hitchcock film The Man Who Knew Too Much. They also co-wrote the theme songs for a bunch of 1960s TV programs, including Mister Ed. (Think Bojack Horseman minus all the pills and booze.)

According to Tammy’s complaint, her grandfather set up a number of trusts which were “specifically designed in more than 15 years of estate planning legal advice with competent estate planning counsel” to hold Jay’s songwriter royalties and “to assure his daughter and granddaughter received their respective shares.” Here’s an exhibit from the complaint mapping out the sub-trusts and the sub-trusts of the sub-trusts. The whole thing is only slightly less confusing than the plot of a Christopher Nolan movie:

Jay died in 2001, and for most of the following years, Tammy received, through Jay’s trust, a share of royalties from the exploitation of his songs. But then, starting in 2015, Travilyn began to serve copyright termination notices on over 50 of Jay’s most valuable compositions, including “Que Sera, Sera,” which became effective in 2019.

As a result of these termination notices, much of Jay’s elaborate estate plan was effectively blown up. Tammy is no longer receiving her share of all of the songwriter’s royalties she had been entitled to per Jay’s trusts, even though Jay used those trusts as a “will substitute” to evidence his testamentary intent. Tammy’s complaint seeks a declaration that Travilyn’s copyright termination notices aren’t valid and that she’s still entitled to royalties.

What Happened?

At this point you may be wondering how Jay Livingston’s carefully considered—and no doubt expensive—estate plan could have suffered this fate. In order to find out, we need to take a look at the Copyright Act’s statutory termination provisions, which give both revocable trusts and Christopher Nolan movies a run for their money in terms of complexity.

I’ve written many times before about copyright termination, a set of statutes designed to give authors the opportunity to regain rights in works they may have signed away when they had little bargaining power. The termination provision at issue in Livingston is Copyright Act section 203(a), which allows authors and their statutory heirs to terminate post-1978 copyright assignments and licenses as early as 35 years after they were originally made. Following termination, the qualifying heirs will “recapture” the assigned rights “notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.” Copyright termination is a use-it-or-lose-it provision, and the termination right can only be exercised during a five-year window before it’s gone forever.

Unfortunately for Tammy, in 1984, one year before Jay created his elaborate estate plan, he assigned his song copyrights to “Jay Livingston Music,” a music publishing company owned by Travilyn. It’s these assignments that Travilyn terminated 35 years later. There will likely be fights in the Livingston litigation about whether the terminations are valid and if they cut off Tammy’s right to receive royalty income, but if so, Tammy will be out of luck.

Copyright Termination and “Estate-Bumping”

It’s not just Tammy. The termination statutes provide an artist’s heirs with a second chance to exploit previously-assigned copyrights, but the statutes can also be used to effectively ruin an artist’s estate plan when rights in copyrighted works have been transferred to a trust or other holding company. This concept of “estate-bumping” is important for trusts and estates lawyers to understand, because it may impact planning decisions made while the artist is still alive.

A good example of estate-bumping in action took place in connection with a lawsuit I defended several years ago between the children of musician Ray Charles and his charitable foundation. Charles told each of his twelve children that he would leave them $500,000 as their sole inheritance, but in exchange they had to agree that they wouldn’t seek anything else from his estate. Charles left the bulk of his estate, including all of the rights in his songs, to the Ray Charles Foundation to benefit the hearing and seeing impaired. Seven of Charles’ children nevertheless served notices under section 304(c) (another copyright termination statute that applies to grants of pre-1978 works), to terminate assignments between Charles and his record labels that predated Charles’ estate plan.

Even though the children had expressly agreed not to challenge Charles’ estate plan, copyright termination rights aren’t waivable by contract, so it didn’t matter what they signed or what Charles actually intended. (Note that the copyrights in “works made for hire” are an exception to the termination statutes; the Ray Charles Foundation asserted that certain of Charles’ compositions weren’t eligible for termination, but the case settled before that issue was decided.)

Copyright Termination as Forced Heirship

One of the interesting features of the copyright termination statutes is that they essentially serve as forced heirship laws. The Copyright Act defines the heirs entitled to serve a termination notice:

- The widow or widower owns the author’s entire termination interest unless there are any surviving children or grandchildren of the author, in which case the widow or widower owns one-half of the author’s interest.

- The author’s surviving children, and the surviving children of any dead child of the author, own the author’s entire termination interest unless there is a widow or widower, in which case the ownership of one-half of the author’s interest is divided among them.

- The rights of the author’s children and grandchildren are in all cases divided among them and exercised on a per stirpes basis according to the number of such author’s children represented; the share of the children of a dead child in a termination interest can be exercised only by the action of a majority of them.

- In the event that the author’s widow or widower, children, and grandchildren are not living, the author’s executor, administrator, personal representative, or trustee shall own the author’s entire termination interest.

Where the artist’s spouse is deceased, as in the Livingston case, the artist’s entire termination interest is held by the artist’s children. Here, as Jay Livingston’s only living child, Travilyn owns 100% of Jay’s termination rights and is entitled to 100% of the recaptured copyrights, even though Jay clearly intended for Tammy to receive a share.

Transfers By Will Aren’t Subject to Copyright Termination

Another interesting aspect of termination rights is that they don’t apply to copyrights that were transferred “by will.” Therefore, if Jay Livingston hadn’t assigned his copyrights to Jay Livingston Music, and had instead bequeathed them directly to Travilyn and Tammy upon his death, that bequest couldn’t be terminated.

What estate planning lawyers unfamiliar with copyright law may not realize is that the termination statutes don’t have any similar exceptions for other transfers, like revocable trusts, which are often used as “will substitutes” by planners. Assignments to a holding company or charitable foundation also have the potential to be undone by a copyright owner’s statutory heirs. This means that unless and until the Copyright Act is amended, planners looking to avoid unintended consequences will need to include copyright interests in a will or pour-over will, even if they place the rest of an artist’s estate in a revocable trust or other instrument.

Bottom line: If the composer of “Whatever Will Be, Will Be” had used a will to transfer copyrights to his heirs, his granddaughter wouldn’t be losing out on royalties. Que Sera, Sera, indeed.

I’ll post updates on the Livingston case as they develop. In the meantime, let me know if you have any comments or questions below, or @copyrightlately on social media.

2 comments

Hi Arron, great article, thank you. Where there is a chance that the heirs and the beneficiaries are different, like here, what are your thoughts on an artist having the author be an LLC under a work-for-hire as a work around? Other than a different term f copyright, any downside?

With the usual caveat that I can’t give legal advice, having the underlying work authored by an LLC as a work for hire would avoid the issue of heirs thwarting estate plans. The problem is that it may also prevent *anyone*—the artist and his/her heirs—from ever being able to terminate rights grants to third party record labels, publishing companies etc. I’ve written about this issue before here:

https://copyrightlately.com/copyright-termination-loan-out-corporations/