The world’s largest record company says it has a clear view of the legal landscape surrounding AI-generated music. The reality is more complicated.

If you’ve been glued to news coverage of the Ed Sheeran trial for the past two weeks, you may have missed an even bigger story from the world of music copyright. While Sheeran attempted to convince a New York jury that he didn’t infringe Marvin Gaye’s classic “Let’s Get It On,” Universal Music Group (UMG) was trying to convince nervous investors that it’s ready to take on the fast-moving wave of AI-generated music that threatens to upend the music industry as we know it.

Sheeran had the easier job.

UMG’s executives clearly wanted to stake out a strong position on AI during the company’s quarterly earnings call on Wednesday, but legal battles over AI-generated music won’t be easy, and will make fights over the I-iii-IV-V chord progression look downright quaint by comparison.

Striking a Discord

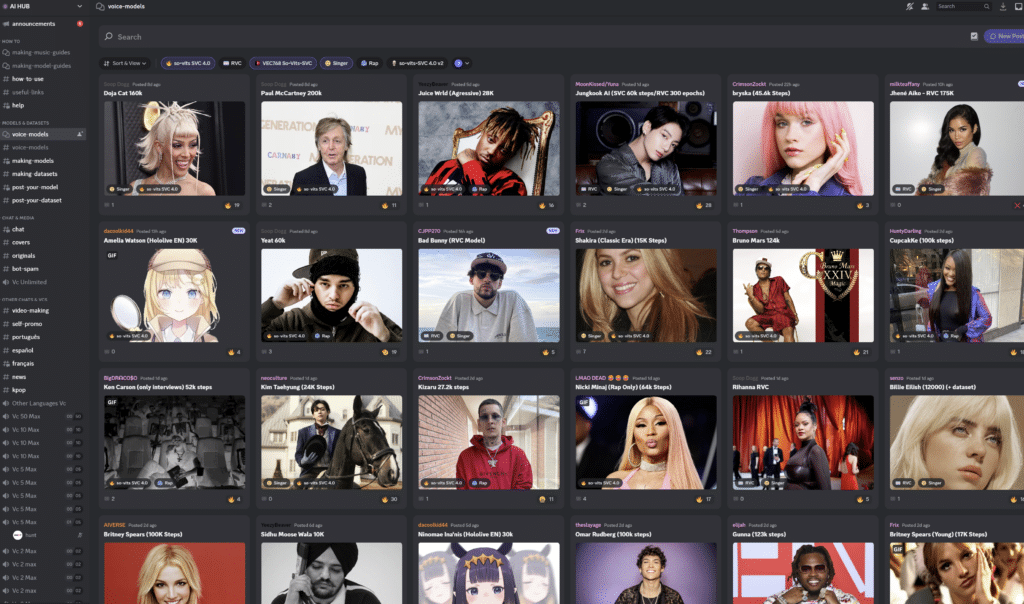

Seemingly coming out of nowhere, AI-generated music is now everywhere. In just over a month, a raft of barely-underground Discord servers like AI Hub have popped up to provide users with access to software—and step-by-step instructions—for creating new songs using hundreds of community-made AI models designed to mimic specific artists’ voices.

The new DIY tools aren’t particularly difficult to use, but even technically-challenged wannabe producers can use off-the-shelf apps like Musicfy and Uberduck to perform voice-to-voice and text-to-voice conversions using models trained on the voices of popular artists.

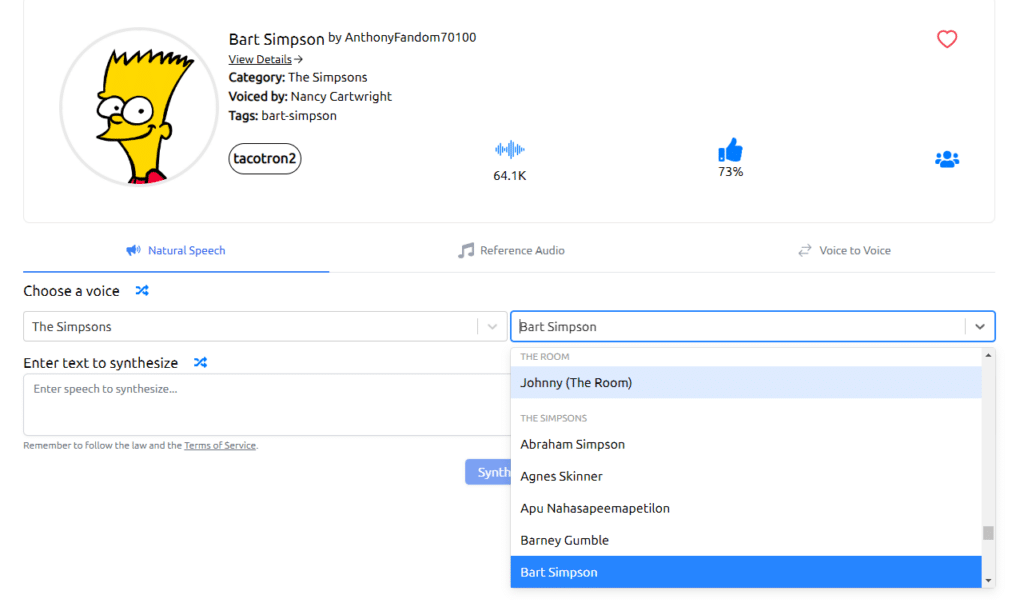

Here’s an example that I created with Uberduck using a simple 64K model of Bart Simpson’s voice (aka actor Nancy Cartwright). It took me all of about three minutes:

Cover Me

For the most part, the music that’s being produced and shared on communities like AI Hub consists of cover versions of existing songs, which are fairly easy to create once you have a working voice model. The vocal track of any preexisting recording can be isolated from the music using a simple software program and run through another piece of software called a voice converter. The resulting vocals are then merged back with the music to create a new track.

Just a few of the thousands of combinations currently making the rounds include the AI Beatles singing Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” AI Freddy Mercury doing Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep” and AI Travis Scott performing. . . pretty much any song you can think of. (Music that’s already digitally enhanced or autotuned seems to provide the best results, which may help explain why hip-hop artists like Scott and Drake have been the subject of so many of these early creations.)

Here are a couple of the more unexpected examples that are up on YouTube as I write this:

From a copyright perspective, these particular tracks are clearly derivative of both the original sound recordings and the underlying musical compositions. But that’s not always the case. For example, if I were to sing my own acapella version of “Here Comes the Sun” into a microphone and run it through vocal conversion software using a George Harrison voice model, the resulting track would implicate the underlying composition copyright, but not the sound recording copyright because no actual sounds from the Beatles version would have been copied. That’s an important distinction to keep in mind as I run through some of the legal issues involved.

UMG’s “View Of The Legal Landscape”—But Is It Correct?

So what does Universal Music Group, the world’s largest record label, have to say about all of this? After all, some of the most buzzed-about AI tracks feature UMG artists like Drake and The Weeknd, including the enormously popular “Heart on My Sleeve.”

On April 26, UMG held an earnings call in which it reported that revenues rose 11.5% year over year to $2.71 billion in the first quarter of 2023, largely driven by successful releases from Morgan Wallen, Taylor Swift, and the aforementioned Drake. But Wall Street analysts were more interested in learning whether the company has formulated a legal strategy around AI.

The comments of UMG’s Chief Digital Officer Michael Nash, in response to a question posed by analyst Omar Sheikh, are worth quoting extensively. My take follows each soundbite below.

“I’m glad that you asked the question about our legal view of AI, because I do think that there’s been a little bit of confusion. It’s a new issue and there’s been some fresh reporting on it with some recent developments. And we’re happy to have the opportunity to be very, very clear about our view of the legal landscape. So let me break it down here. First of all, in terms of copyright, to reiterate our very clearly articulated position . . . sophisticated generative AI that’s enabled by large language models, which trains on our intellectual property, violates copyright law in several ways. Companies have to obtain permission and execute a license to use copyrighted content for AI training or other purposes, and we’re committed to maintaining these legal principles.”

Michael Nash, UMG’s Executive Vice President, Chief Digital Officer (comments made during UMG’s Q1 2023 earnings call, April 26, 2023)

Inputs, Outputs, Converters, and Models: A (Hopefully) Simple Explanation of the Tech and the Law

Training the Model

As I’ve written before, AI copyright issues need to be analyzed separately with respect to the input and output phases of AI generation. The comments from Michael Nash quoted above really only speak to the input phase, during which audio recordings are copied to a dataset that’s then used to train a voice model. But once created, the voice model is just a set of parameters. It isn’t human-readable and does not contain copies of any audio recordings. (Most voice model files are actually quite small.) While the intermediate copying of audio files during the training phase may implicate UMG’s sound recording copyrights, the actual model doesn’t.

A separate copyright analysis applies to any particular output generated by the model, which is a new sound recording that may or may not infringe one of UMG’s copyrighted compositions or sound recordings depending upon how the tool is used.

Converting the Voice

I’ll use some simple examples to help illustrate all of this. Let’s say that Janet wants to produce a Drake voice model. She would create a dataset of sound files consisting of Drake acapella vocals (stripped from the music tracks using a vocal separator) and run the data through software used to train the voice model. By making these intermediate copies of the original Drake recordings, Janet would be implicating UMG’s sound recording copyrights (subject to any fair use or other defenses she may be able to assert).

Now suppose Janet’s roommate Chrissy comes along and wants to use Janet’s voice model to make it appear that Drake is singing “The Best Day Ever” from SpongeBob SquarePants. Chrissy uses voice conversion software to convert the SpongeBob track and ends up with something atrocious like this:

Copyright Law, What Say You?

Chrissy has created an unauthorized derivative work of the SpongeBob track (which probably won’t make Sire Records happy), but she likely hasn’t implicated any copyright interests in the UMG-owned Drake recordings that were used by Janet to train the original model. (Chrissy may also face liability under some other non-copyright legal theories, but I’ll get to those in a bit.)

Now suppose Janet’s other roommate Jack wants to use Janet’s voice model, but he wants to use it with original music and lyrics he’s written himself. Jack sings the vocals into a microphone connected to his computer, doing his best to match Drake’s tone and flow, converts the track to Drake’s voice using Janet’s model, and then merges the resulting vocal output with his beat track. The end product may look something like “Heart on My Sleeve” or “Winter’s Cold,” each of which has already racked up millions of plays.

So, to recap, UMG might try to sue Janet for copyright infringement for making intermediate copies of Drake sound recordings to train her model, but it probably wouldn’t have a viable copyright claim against either Chrissy or Jack, assuming they just used Janet’s model and didn’t contribute or assist her in creating it. So unless UMG is able to stop the Janets of the world from training AI models before they get in the hands of the Chrissys and Jacks of the world, current U.S. copyright law really doesn’t seem to give UMG a ton of options.

By the way, I purposely used the names of individuals in my example to make a point. In his comments, Nash said that “Companies have to obtain permission and execute a license to use copyrighted content for AI training or other purposes.” That may be true, but the fact is that most model creation is being done by kids that probably aren’t even out of high school, not deep-pocketed companies. No wonder I’m getting flashbacks to 2003.

Soundalikes: No Actual Sounds, No Actual Infringement?

Nash went on to make the following comment about music copyrights:

“With respect to voice, I think there’s been some confusion here, and I want to be really, really clear on this point. We own all sounds captured on a sound recording. That is, in fact, the very nature of sound recording copyright and ownership.”

Michael Nash, April 26, 2023

Again, Nash’s statement is correct as far as it goes. UMG’s sound recording copyrights encompass all of the sounds captured on its tracks—the vocals as well as the music. But UMG’s copyrights don’t extend to an artist’s “voice” as distinct from the particular fixation of that voice on any given track. And the copyright in a sound recording doesn’t extend to independently created “soundalike” recordings—even if one performer deliberately sets out to simulate another’s performance as closely as possible.

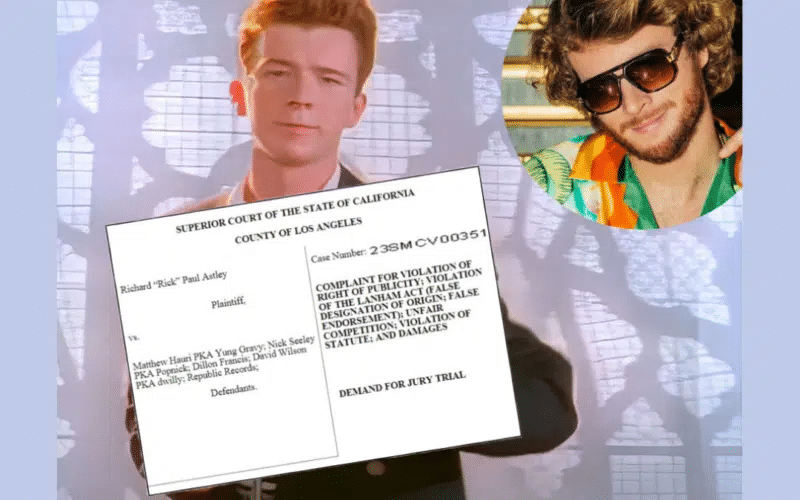

I discussed the law of soundalikes extensively in my recent article about Rick Astley’s pending lawsuit against Yung Gravy over an authorized cover version of “Never Gonna Give You Up.” As a brief refresher, Section 114(b) of the Copyright Act limits the exclusive rights granted to the owner of a sound recording copyright to (1) the right to duplicate the “actual sounds” fixed in the recording, and (2) the right to prepare derivative works in which those actual sounds are “rearranged, remixed, or otherwise altered in sequence or quality.”

“[T]he world at large is free to imitate or simulate the creative work fixed in [a] recording (like a tribute band, for example) so long as an actual copy of the sound recording itself is not made.”

VMG Salsoul, LLC v. Ciccone, 824 F.3d 871, 888 (9th Cir. 2016)

To go back to my previous examples, if Chrissy runs a recording of SpongeBob’s “Best Day Ever” through a sound converter using a Drake voice model, the resulting song may qualify as an “alteration” of the actual sounds from the SpongeBob recording—but it probably wouldn’t implicate the copyright in any Drake recordings (assuming Chrissy didn’t copy any of the actual sounds from those recordings). And if Chrissy instead sings her own cover version of “Best Day Ever” and runs those vocals through the sound converter (like I did with the Bart Simpson model above), the resulting output probably won’t infringe any sound recording copyright at all. (Note that Chrissy would still need to obtain a license to use the underlying “Best Day Ever” composition.)

This all raises the question of how and why UMG was able to send a successful DMCA takedown notice to remove “Heart on My Sleeve” from YouTube and various streaming services. As reported last week by The Verge‘s Nilay Patel, the label apparently considered the Metro Boomin producer tag appearing at the start of the song to be an unauthorized sample, and “the DMCA takedown notice was issued specifically about that sample and that sample alone.” Without that, it’s difficult to see how the track implicates UMG’s copyright interests given that it doesn’t duplicate the actual sounds from any Drake recording.

Non-Copyright Claims

In what turned out to be quite a long answer, Nash next turned to potential remedies outside of copyright law:

“Now we have other remedies beyond copyright law. There are various exploitations of generative AI, which we’ve seen recently that are exploitations without authorization running about a number of protections, including trademark, name and likeness, voice impersonation, right of publicity, and all these are instruments that can protect our work . . . And specifically, soundalikes which serve to confuse the public as to the source or origin, or which constitute a commercial appropriation of likeness in the form of a distinctive voice, those are all clearly illegal.”

Michael Nash, April 26, 2023

It’s unclear who exactly Nash was referring to when he said that “we” have remedies including under trademark and right of publicity law. Typically, artists, not labels, retain their rights of publicity, which often include the right to control the use of name, voice, likeness and other indicia of an individual’s identity. Artists also may own registered trademarks in their names for use as source identifiers.

While artists may license these rights to their record labels, it isn’t clear that the label would itself have standing to pursue a right of publicity or trademark infringement claim directly against the creator of a soundalike, at least not without the artists’ consent. We’ve already seen musician Grimes announce that she was on board with anyone using her voice in AI-generated tracks, offering to “split 50% royalties on any successful AI-generated song that uses my voice.”

But regardless of who may assert them, right of publicity and trademark claims historically haven’t been successful when an individual’s name or an impersonation of their voice is used in connection with expressive works (which are generally protected by the First Amendment), as opposed to a garden variety commercial advertisement. As I explained in my discussion of the Rick Astley lawsuit, right of publicity and trademark law provided viable claims to Bette Midler and Tom Waits when imitations of their voices were used in advertising. However, as the proliferation of “tribute bands” with clever names like “The Red Not Chili Peppers,” “Noasis” and “Nearvana” demonstrates, the mere act of “vocal impersonation” typically isn’t unlawful outside of the advertising context unless it’s done to confuse or mislead.

In addition, the fact that the Copyright Act expressly permits soundalikes (so long as no actual sounds are copied) has caused at least a few courts to hold that right of publicity claims are preempted by the Copyright Act—especially in situations where the defendants obtained sync licenses giving them the right to record a particular musical composition. For example, about 15 years ago, a district court in Michigan dismissed right of publicity and trademark claims brought by the group The Romantics when Activision hired another band to sing the group’s hit “What I Like About You” on one of Activision’s “Guitar Hero” video games.

It didn’t matter that the cover version allegedly sounded indistinguishable from the original Romantics’ version. Because no actual sounds were copied from the original record used, the band couldn’t assert a copyright claim. In addition, the court found that the right of publicity claim was preempted because it would stand as an obstacle to federal law which, the court held, “expressly disallows any recourse” for soundalikes. In case you’re interested, here’s a link to a journal article I wrote about the Romantics v. Activision case a loooong time ago back when we had paper.)

What’s Next?

Finally, speaking to the question of whether new copyright legislation was needed to prevent generative AI from eating the music industry’s lunch, Nash said:

We believe that most key markets’ copyright laws are fit for purpose right now, and don’t—we don’t see a requirement for new legislation per se. But I think it’s very important governments around the world interpret and enforce the existing laws correctively [sic]—correctly and actively.

Michael Nash, April 26, 2023

I’m not sure that UMG is entirely correct here. Existing copyright law may be able to deal with low-hanging fruit, such as the unlicensed cover versions that are currently popular and relatively easy to churn out. But I don’t see how the Copyright Act could be used to prevent someone from singing an original song and then using a voice converter to mimic the vocals of a particular artist. We can debate whether or not copyright law could or should be used to stop this sort of thing; my point is that I don’t think it does.

Meanwhile, right of publicity is entirely a creature of state law, a disparate patchwork of individual statutes. Not only do these laws often conflict with each other, but some states don’t even protect an interest in one’s “voice” at all. There have long been calls for Congress to pass a federal right of publicity law. It would be fascinating if AI ends up providing the jolt needed to spur such legislation, which ideally would also address the interplay between the right of publicity and section 114(b) of the Copyright Act.

Finally, I think it would be wrong to assume that there’s necessarily complete alignment between artists and record companies on the issue of AI-generated music. Labels certainly may have a legitimate interest in ensuring that their official releases aren’t competing with AI-generated tracks. (They may also be interested in licensing their sound recordings for AI training purposes.) And at least some artists may view AI as a positive way for them to increase name recognition and drive up the value of their individual brands, figuring that it will help them sell merch and fill concert venues. At least until the computers start touring, that is.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Hit me up in the comments below or on social media @copyrightlately. Meanwhile, if you’re interested in reading the entirety of UMG’s comments about AI-generated music, here’s a link to the full transcript.

2 comments

Thanks for another terrific article! But a clarification, please. At one point you state: Nash said that “Companies have to obtain permission and execute a license to use copyrighted content for AI training or other purposes.” That’s certainly true,

Is that certain at this point? I thought that was still TBD as the cases proceed.

Hi Jeremy – Thanks so much! And good catch – you’re correct that the use of copyrighted content for training purposes is very much an open legal issue. I’ve fixed the sentence you quoted above.

Best,

Aaron