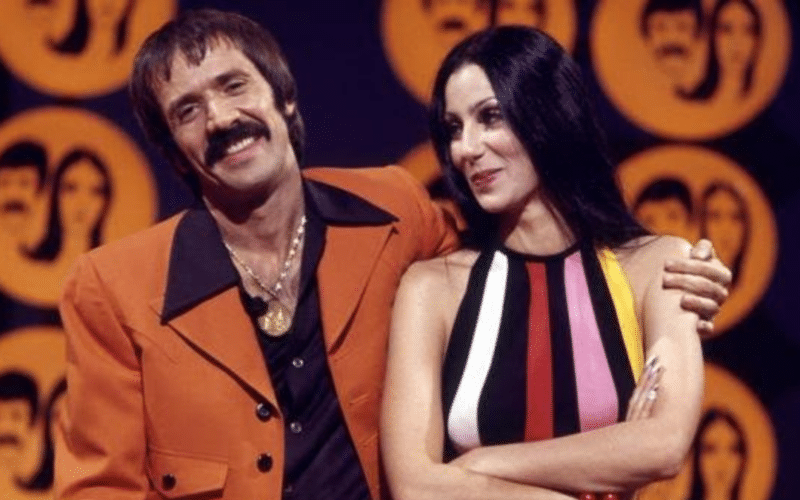

Does a copyright termination by Sonny Bono’s heirs trump Cher’s marital settlement agreement? Copyright and family law intersect in Cher v. Bono.

As I’ve discussed before here on Copyright Lately, copyright termination is one of the thorniest areas of copyright law. But add in some family law, community property and trust & estates issues and you’ve got yourself a whole ‘nother level of complicated. Cher’s new complaint (read here) against Mary Bono touches on all of this and more. I’ll do my best to make sense of the lawsuit and offer my thoughts on which side I think is likely to prevail. (Spoiler alert: it’s Cher.)

UPDATE—March 16, 2023—In a long-awaited ruling, the court allows Cher’s royalty lawsuit to proceed despite copyright termination notices from Sonny Bono’s heirs. Full story here.

Cher and Cher Alike

First, a brief (and somewhat simplified) overview of the facts: After Cher’s marriage to her former husband and performing partner Sonny Bono ended in divorce, Sonny and Cher entered into a marital settlement agreement in which they agreed to an equal division of their community property assets under California law. Per the agreement, Sonny assigned Cher a 50% interest in musical composition and record royalties in the songs he had written or acquired during their marriage. During his lifetime, Sonny paid these royalties to Cher, and after Sonny died in 1998, his widow, Mary Bono, continued to do the same. Sonny Bono’s heirs later transferred their right to receive royalties to the Bono Collection Trust, subject to the obligation to pay Cher her 50% interest in the royalties.

In 2016, Sonny Bono’s heirs issued a notice of termination under Copyright Act section 304(c) to various music publishers and other companies to whom Sonny had previously assigned rights in his musical compositions. At first, the Bono Collection Trust’s publishing administrator continued to pay Cher royalties pursuant to the marriage settlement agreement. But then, in September 2021, representatives of the trust began to take the position that the termination of Sonny’s previous copyright grants also had the effect of terminating the stream of composition royalties that Sonny had previously assigned to Cher in their settlement agreement. The trust advised Cher that it would no longer account or pay for her share of royalties. None too pleased about Mary Bono’s attempt to turn back time (sorry), Cher sued for a declaration of rights and for breach of the marital settlement agreement.

It’s important to note that Cher’s lawsuit does not challenge the Bono heirs’ right to terminate Sonny’s prior copyright grants. Instead, Cher argues that, by doing so, Mary Bono is not relieved of the contractual obligation to continue paying Cher’s royalty interest from the future exploitation of the compositions.

Pay Mrs. Robinson

Cher’s lawsuit is actually quite similar to a case involving another famous musical couple, Smokey and Claudette Robinson. As part of their divorce settlement, Claudette was awarded a 50% interest in Smokey’s copyrights, per California’s community property laws. Years later, Smokey issued statutory termination notices on his publishing and record companies. Like Mary Bono, Smokey took the position that those termination notices had the effect of extinguishing his subsequent agreement with Claudette. Robinson v. Robinson was settled out of court fairly quickly, before the court could issue any dispositive rulings in the matter. However, the arguments made by the parties in that case are likely the same ones that will be made in the Cher v. Bono lawsuit. Another interesting fact: the Central District of California judge assigned to the Cher case, John Kronstadt, is the same judge who presided over the Robinsons’ short-lived legal battle.

One of the principal legal issues in Robinson was the extent to which terminated copyright interests should be treated as community property under California family law, or as the artist’s separate property pursuant to federal law, under which recaptured rights vest solely in the artist or his heirs. The answer to this question in turns in part on whether the laws are in “irreconcilable conflict,” such that federal copyright law trumps state community property law pursuant to the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause and the Copyright Act’s express preemption provision, set forth in section 301.

In the Robinson case, Claudette argued that she was a co-owner of Smokey’s recaptured copyrights, which presents a closer preemption question than the one at issue in Cher v. Bono. Based on the allegations in the complaint, Cher isn’t claiming an interest in Sonny’s recaptured copyrights, but rather only an economic interest in royalties generated from the copyrighted works.

The Right to Receive Royalties Isn’t a Copyright Interest

The better view is that there is no irreconcilable conflict between federal and state law here. The Copyright Act only preempts state law insofar as it grants legal or equitable rights that are equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright, as set forth in section 106 of the Copyright Act. Among these exclusive rights are the rights to reproduce, distribute and prepare derivative versions of the copyrighted work. But the right to receive royalties isn’t one of the exclusive rights granted under federal copyright law, and the assignment of these rights would appear to be governed solely by state law contract and community property principles.

If Cher indeed makes this argument (and I expect she will), she’ll find support in the Ninth Circuit via Yount v. Acuff Rose-Opryland, in which the court addressed whether the right to receive royalties is a copyright interest such that the royalty right is affected by the copyright owner’s original and renewal term. The Yount court concluded that a royalty interest does not constitute an interest in the underlying copyright, but rather arises out of a contractual relationship. “[A] royalty interest does not bespeak an interest in the underlying copyright itself—a royalty is simply an interest in receiving money when the owner of the copyright exploits it.” While the Yount case dealt with royalties earned during the renewal term of a copyright, the principles relied on by the court should apply with equal force to royalty rights following a termination.

Cher will also find support in the text of the Copyright Act’s termination provisions itself, which provide that termination affects “only those rights covered by the grants that arise under this title, and in no way affects rights arising under any other Federal, State, or foreign laws.” In addition, termination only applies to the grant of copyright or of “any right under a copyright.” Sonny’s marital settlement agreement does not appear to have granted any copyright interest to Cher, as opposed to the right to receive royalties, which are purely contractual in nature.

The Bottom Line

In an article published in Bloomberg, Mary Bono’s attorney was quoted as saying “The Copyright Act allows Sonny’s widow and children to reclaim Sonny’s copyrights from publishers, which is what they did.” But if that’s all they did, Cher wouldn’t have had any reason to file her lawsuit. I think there’s a fundamental difference between recapturing the copyrights (which allows the Bono heirs to enter into fresh license agreements with third parties) and taking the additional position that the terminations cut off Cher’s contractual right to royalties from the future exploitation of those rights.

According to my search of Copyright Office records, the Bono heirs’ termination notice was recorded on October 14, 2016 and was served on all of the biggest music publishers, including Universal Music, Sony/ATV and literally two dozen others. Rights in the earliest noticed compositions were scheduled to be recaptured in 2018. It seems exceedingly unlikely that Bono’s heirs didn’t promptly replace the previous revenue streams with new or renegotiated grants at that time. If so, they’ve been receiving royalties generated by the new deals for three years, and have continued paying Cher her 50% interest during that time, right up until the lawsuit. This demonstrates the decoupled nature of the termination rights and the marital settlement agreement.

The result might be different if the settlement agreement only promised Cher royalties generated from a specific, now-terminated, copyright license. But insofar as it contractually required Sonny Bono and his successors to pay royalties earned from any exploitation of the copyrights, the ultimate source of those royalties shouldn’t matter. (Unfortunately, Cher’s attorneys didn’t attach any of the relevant agreements to their complaint, so we can’t yet verify exactly what the settlement agreement provided.)

It remains to be seen whether Cher v. Bono will follow in the footsteps of Robinson and settle early. If it doesn’t, I think Mary Bono and the Bono Collection Trust are going to have a tough time avoiding Sonny and Cher’s marital settlement agreement. Agree or disagree? Let me know in the comments below or on the @copyrightlately social media accounts. In the meantime, you can read the full complaint below.

View Fullscreen

2 comments

Did Mary win her dismissal motion?

As of today (August 29), it’s still under submission with the court. Stay tuned!