The release of a new film in the “Predator” franchise may hinge on an obscure but increasingly important aspect of copyright termination.

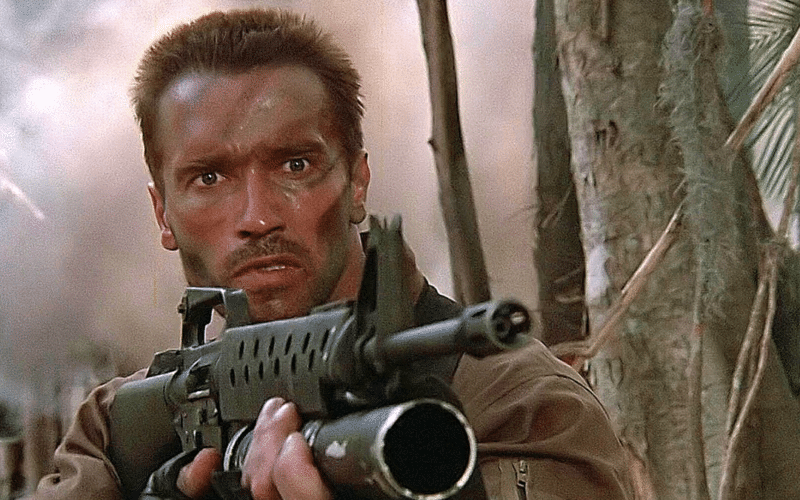

In November 2020, right around the time we were all gearing up for a festive pandemic-themed Thanksgiving, reports emerged that the “Predator” motion picture franchise made famous by the original 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger film would be returning for a fifth installment. 20th Century Studios, now part of the Walt Disney Company, has reportedly engaged “10 Cloverfield Lane” director Dan Trachtenberg to direct. And while no release date has been announced for the new film, don’t be surprised if the project is now fast-tracked as a result of a pair of dueling copyright termination lawsuits filed yesterday in two different federal courts.

Thomas v. Fox

The first case (read here) was filed in the Northern District of California on behalf of Jim and John Thomas, two brothers who wrote “Hunters,” the original screenplay on which “Predator” was based. According to the plaintiffs’ complaint, they optioned rights in their screenplay to Twentieth Century Fox in 1985, which Fox exercised in 1986. “Predator,” the derivative film based on the screenplay, was released in theaters in June 1987. The lawsuit seeks a declaration that the brothers have validly terminated their prior rights transfer pursuant to provisions of the Copyright Act which allow authors to recapture rights in their works after 35 years.

Fox v. Thomas

The second lawsuit (read here) was filed by Twentieth Century Fox against the Thomas brothers in the Central District of California, and essentially seeks an opposite declaration of rights—a finding that the notices of termination are not valid and that Fox may legally continue to produce “Predator” films for least a few more years going forward. According to the Fox complaint, the Thomas brothers are attempting to “prematurely terminate” Fox’s rights at a time that it is “investing substantial time, money and effort in developing another installment in its successful Predator franchise.” Fox says that the 35 year termination period needs to be calculated, not from the date of the 1986 rights transfer, but rather from the date “Predator” was first released in 1987.

Copyright Termination and the “Alternative Calculation Method”

So who’s right? The answer may depend on a relatively arcane aspect of copyright termination law, but one that’s poised to become increasingly important as more and more lucrative 1980’s and 90’s motion picture franchises become eligible for termination.

Under section 203(a) of the Copyright Act, copyright grants executed after January 1, 1978 may be “effected at any time during a period of five years beginning at the end of thirty-five years from the date of execution of the grant.” However, if the grant “covers the right of publication of the work,” slightly different rules apply. In this case, the five year period “begins at the end of thirty-five years from the date of publication of the work under the grant or at the end of forty years from the date of execution of the grant, whichever term ends earlier.”

This alternative calculation method was added at the behest of book publishers. They argued that, because publication contracts are often signed before a book is written, years might go by before a book is finally published. In such situations, calculating the termination period from the date of transfer could provide the publisher with significantly fewer than thirty five years to exploit the work subject to the copyright grant. As the House Report to the 1976 Copyright Act notes, the “alternative method of computation is intended to cover cases where years elapse between the signing of a publication contract and the eventual publication of the work.”

“Termination of the grant may be effected at any time during a period of five years beginning at the end of thirty-five years from the date of execution of the grant; or, if the grant covers the right of publication of the work, the period begins at the end of thirty-five years from the date of publication of the work under the grant or at the end of forty years from the date of execution of the grant, whichever term ends earlier.”

17 U.S.C. § 203(a)(3)

But it’s not just books that are subject to “publication,” and the law doesn’t expressly limit the alternative calculation method to book publishing contracts. Motion pictures are considered to be “published” when one or more copies are distributed to the public or offered to motion picture distributors for public performance. Once a motion picture made from a screenplay is published, the underlying screenplay is deemed published to the extent it’s contained in the published film.

Proper Calculation is Critical

I’ll use the actual facts of the “Predator” case to show why the particular calculation method used can have important consequences for the timing and validity of a termination notice.

The Thomas brothers entered into their option agreement with Fox on January 22, 1985, with Fox exercising the option on April 16, 1986. For purposes of the termination statute, the latter date is when rights in the “Hunters” screenplay were actually transferred. If the normal calculation period applies, termination could take effect between April 16, 2021 (35 years from execution) and April 15, 2026 (the end of the five year termination window). Here, the Thomas brothers’ initial termination notice (served in 2016) set forth an effective date of April 17, 2021.

But what if the alternative calculation method applies? According to Fox’s complaint, the 1986 transfer of rights in the “Hunters” screenplay expressly covered the right of publication. In this case, the five year termination window would begin on the earlier of June 12, 2022 (35 years from the “publication” of “Predator”) and April 16, 2026 (40 years from execution of the grant).

After Fox raised an objection to the Thomas brothers’ initial termination notice on the grounds that the alternative calculation method applied, the writers served a second termination notice with an effective date of June 14, 2022—35 years from the film’s release date.

But there’s one more wrinkle to the case: section 203(a) requires that notice be given at least two years before the effective date of termination. The writers’ second termination notice wasn’t served until January 12, 2021—less than two years before the purported June 14, 2022 effective date.

Presumably recognizing that the second termination notice wouldn’t provide enough notice, the Thomas brothers simultaneously served a third notice. This one has an effective date of January 13, 2023—just over two years after service but still within the five year termination window. Fox doesn’t appear to be challenging the validity of this notice in its new complaint.

So When Will “Predator” Be Terminated?

To recap: if the initial termination notice is valid, Fox’s right to make new “Predator” motion pictures will be cut off imminently (as of April 17, 2021). If, on the other hand, only the final termination notice is valid, Fox’s rights won’t lapse until January 13, 2023. Whether this will be enough time to get the fifth installment of “Predator” out of development and into theaters remains to be seen.

Given the importance of properly calculating the termination date, it’s surprising that there haven’t been a lot of cases out there construing copyright termination’s “alternative calculation method.” A relatively recent Second Circuit case, Baldwin v. EMI Feist Catalog, touched on it a bit, finding that the alternative calculation method doesn’t apply where a work was previously published at the time of the grant. In an apparent nod to this ruling, Fox specifically alleges in its complaint that the “Hunters” screenplay had never been published prior to the release of the “Predator” film.

Nimmer’s copyright treatise seems to take the position that the alternative calculation method shouldn’t apply to motion pictures, as it was “intended to be triggered only by a grant of what is referred to in industry usage as ‘publication rights,’ which are limited to book and periodical publication.” But while that may have been the genesis of the alternative method, on the face of the statute it’s not limited to book publishing.

It’s also important to note that the alternative calculation method arguably doesn’t just apply to the grant of publication rights, but to any grant that “covers” publication. So to be safe, screenwriters are almost always better off calculating termination dates conservatively, using the release date of the film instead of the date of transfer. Keep in mind though that things can get a bit more tricky if there was a lengthy delay between the transfer and publication dates. In this case, “forty years from the date of execution of the grant” may be the critical date.

Copyright termination is one of my favorite topics, so let me know if you have questions or comments below. Or feel free to reach out on one of my social media accounts @copyrightlately. Now go get to the choppa!

The Thomas Complaint:

View FullscreenThe Fox Complaint:

View Fullscreen

4 comments

Fascinating! I don’t remember covering this in my copyright course in law school. Link to a good explainer on termination for the casual copyright observer who went on to do more boring stuff?

If you have access to it, I would probably read Bill Patry’s treatise chapter on copyright termination. There are also a number of articles on the internet on copyright termination basics, but I can’t vouch for their accuracy

I wrote a spec script in 1986 that was released as a film in 1988. So the effective date would 2023, right? It’s too late to file two years prior to that. But can I file now, with an effective date in 2024, thus giving them two years notice?

Ok, I’m going to preface this by saying this is NOT legal advice – but you should be in the window. Send me an email if you want to chat more.