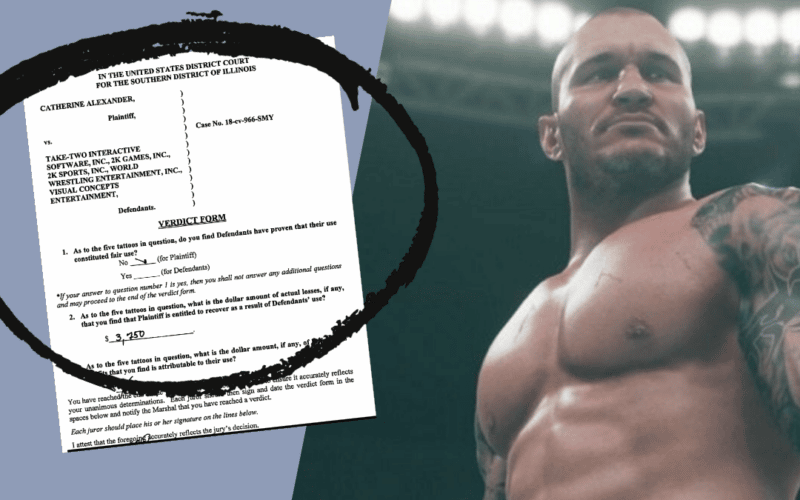

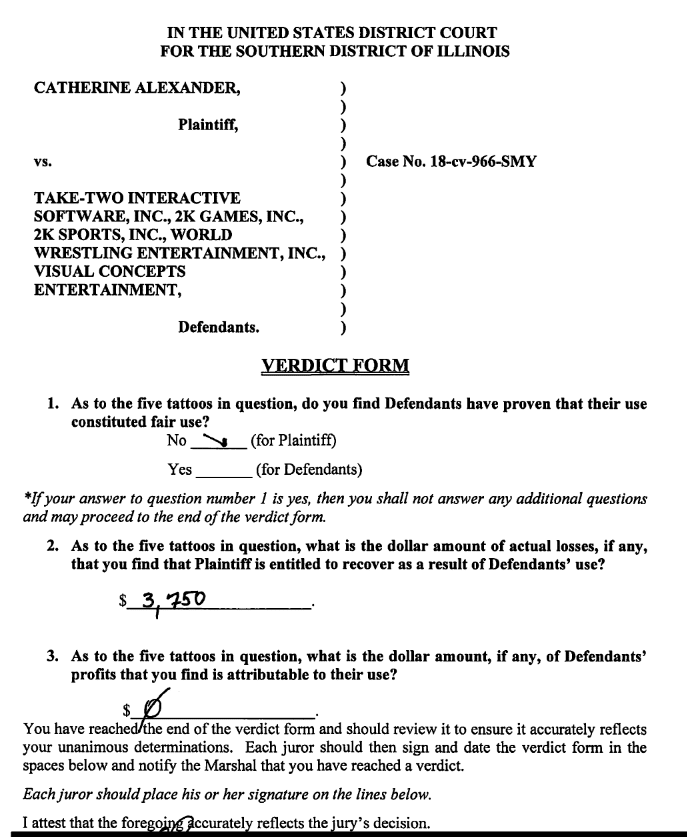

An Illinois federal jury awarded Catherine Alexander only $3,750 in damages for Take-Two Interactive and WWE’s use of tattoos she made for Randy Orton in their video games, but the implications of the ruling go much further.

At the conclusion of a five-day trial last week pitting tattoo artist Catherine Alexander against Take-Two Interactive and WWE, an eight-member jury on Friday found that defendants committed copyright infringement by incorporating Alexander’s tattoo art into a realistic depiction of wrestler Randy Orton for use in their “WWE 2K” series of video games.

What Happened

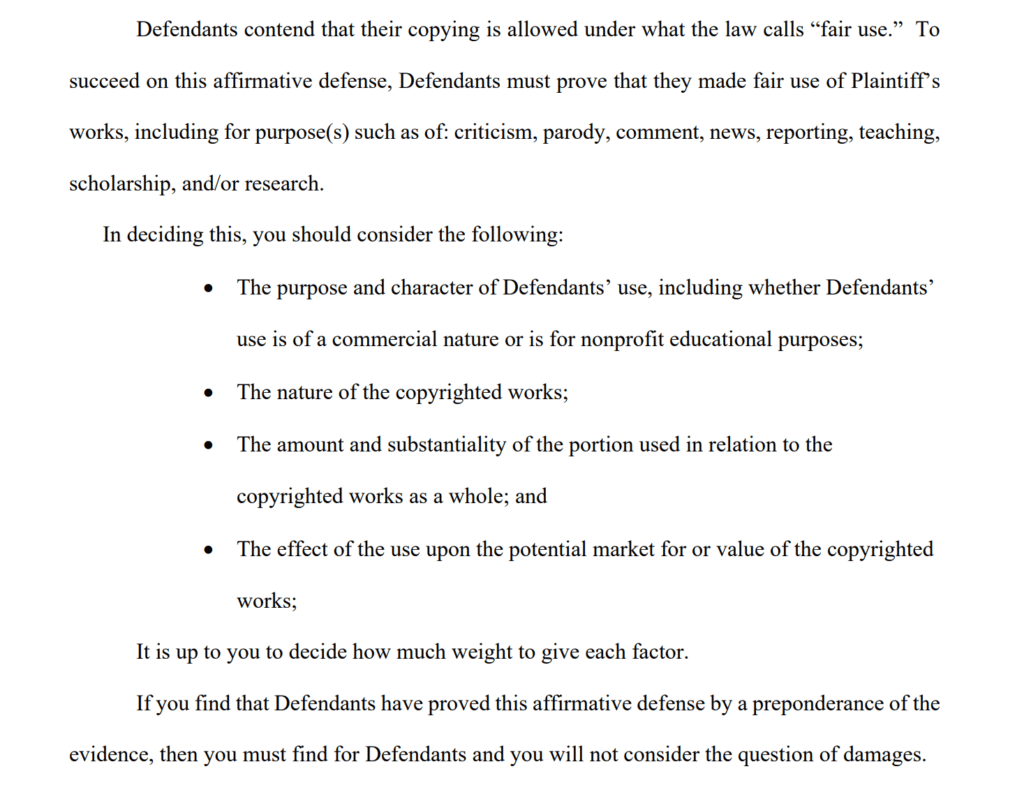

Despite a number of solid affirmative defenses—including implied license, de minimis use and waiver—the jury was only asked to determine whether defendants had proven that their conduct qualified as a fair use under the Copyright Act. Ironically, that’s the one defense that, per the Supreme Court’s recent pronouncement in Google v. Oracle, should have been decided by the trial judge.

The jury rejected the fair use defense and found that Alexander was entitled to $3,750 in actual damages. It also found that none of the profits defendants earned from the sale of their video games were attributable to the use of Alexander’s tattoos.

From a purely economic standpoint, Alexander’s case was the litigation equivalent of a tattoo fail. That $3,750 works out to a measly $71 for each month the case has been pending. Because Alexander didn’t register copyrights in her tattoo designs until shortly before filing her complaint in 2018 (long after the claimed infringement first occurred), she’s not entitled to seek recovery of her attorneys’ fees under the Copyright Act.

What’s at Stake

If the massive drain on time, money, and judicial resources spent on achieving the result in Alexander weren’t bad enough, the potential implications of the case—and the district court’s decision to hand it to a jury in the first place—are much worse.

Simply put, the ruling calls into question the ability of tattoo owners to control the right to make or license realistic depictions of their own likenesses. Permission for these kinds of uses would instead need to be obtained from the tattoo artist, who could demand payment or deny permission altogether.

At the same time, content creators may need to worry about making even incidental reproductions of a copyrighted tattoo design without permission, which could deter them from accurately depicting an individual’s identity in any number of expressive works protected by the First Amendment. If the mere reproduction, distribution or display of a tattooed individual’s likeness is infringing, subject only to a jury’s whims on fair use, it could cause major disruptions to tattoo industry norms and entertainment industry practices alike. More on all of this below. But first, here’s a quick recap of the trial verdict:

How We Got Here

As I wrote last week, the deck was stacked against the defendants before trial even started. In 2020, Southern District of Illinois judge Staci Yandle issued a key ruling when she denied defendants’ motion for summary judgment and granted Alexander’s motion for partial summary judgment.

The court could have found, based on the undisputed facts, that defendants’ use of the tattoos as part of a realistic depiction of Orton’s likeness was: (1) subject to an implied license based on the parties’ conduct and tattoo industry custom; (2) so trivial, fleeting or incidental as to be de minimis; or (3) a fair use, on the theory that the original purpose of the tattoos was body art, while defendants’ purpose was to accurately and realistically depict Orton’s likeness in their games. A ruling for defendants on any one of these theories would have ended the case. The district court in the very similar Solid Oak Sketches v. 2K Games found for the defendants on all three affirmative defenses. By contrast, Judge Yandle rejected all of them (without even mentioning Solid Oak Sketches in her summary judgment order).

In addition, in granting Alexander’s motion for partial summary judgment, the court found that Alexander held valid copyrights in the tattoo designs at issue and that defendants copied those works. In another order issued shortly before trial, the court ruled that defendants would be “liable for copyright infringement unless they can establish an affirmative defense to their usage.”

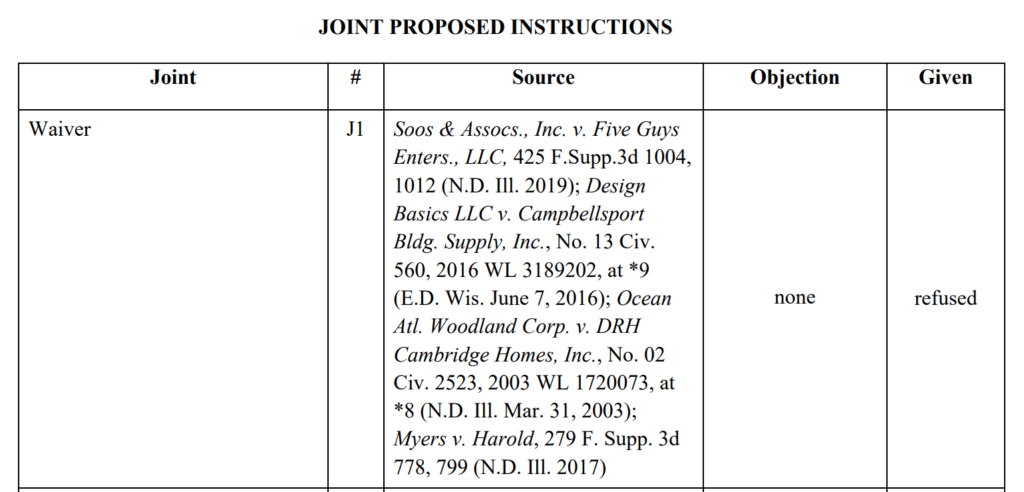

But then, the court began removing those defenses from the jury’s consideration. The first one to go was the de minimis defense, which the court rejected before trial. Next, following the conclusion of evidence, the court refused to give the jury any instruction on implied license—even though both parties requested one. The judge likewise refused to give defendants’ proposed jury instruction on waiver, even though plaintiff hadn’t objected to it.

This left only the fair use defense remaining for the jury. The court gave only a single, bare-bones instruction that essentially just parrots the statutory language from section 107 of the Copyright Act, making it less than helpful:

Fair use is a mixed question of law and fact, which means that the jury is only supposed to resolve disputed factual issues underlying the defense, while the ultimate decision on fair use is supposed to be made by the court. Consistent with this law, the final pretrial order entered by the court on September 19 stated (correctly) that fair use was an issue of law for the judge to decide:

So basically, the only defense that was presented to the jury should have been decided by the judge, and the defenses that should have been presented to the jury weren’t. This confluence of events may help explain why the jury came back with its verdict in favor of Alexander.

Where We’re Heading

In refusing to dismiss the Alexander case and instead handing it to a jury to decide, the court has effectively ruled that anyone with a tattoo is not in control of the uses to which his or her likeness is put. Under the decision, unless you expressly negotiate the terms of an assignment or license with your tattoo artist up front, there’s nothing to stop the artist from objecting later to a use she doesn’t approve.

The fundamental problem with the court’s ruling and the resulting jury verdict is that it puts copyright law in a very uneasy tension with two other constitutional rights, the right to bodily autonomy and the First Amendment.

Bodily Autonomy

Law professor Aaron Perzanowski, the nation’s foremost legal scholar on tattoos, has written extensively about tattoo industry norms and customs. Historically, the relationship between tattoo artists and their clients has been symbiotic and free from legal conflict. Artists typically don’t register copyrights in their tattoos, and they almost never file lawsuits when their works are reproduced as they appear on clients’ bodies. In a 2013 law review article entitled “Tattoos and IP Norms,” Perzanowski wrote that “Both during and after the design process, tattooers consistently demonstrate a respect for client autonomy . . . once an image is created on the client’s skin, tattooers uniformly acknowledge that control over that image, with some limited exceptions, shifts to the client.”

Among those limited exceptions are situations in which a tattoo design is used as a work disconnected from the body on which it appears. For example, if a client were to license the reproduction of a tattoo design by itself (e.g., the sale of temporary tattoos featuring the design), that could exceed the scope of the tattoo artist’s implied license.

But commercial uses of the client’s likeness that happen to incidentally reproduce the tattoo are fair game per industry custom and practice. One artist that Perzanowski interviewed for his article commented that “[Claiming control over the client’s use of the tattoo is] ridiculous. That goes against everything that tattooing is. A tattoo is like an affirmation that it is your body . . . that you own your own self, because you’ll put whatever you want on your own body. For somebody else to say, ‘Oh no, I own part of that. That’s my arm.’ ‘No, it’s not your fucking arm, it’s my fucking arm. Screw you.'”

Perzanowski tweeted the following after the jury’s verdict in Alexander:

Fair Use as Free Speech

The U.S. Supreme Court has already declared video games to be “expressive works” entitled to the same First Amendment protection given to motion pictures and literature. So while some may take solace in the fact that this particular ruling was about the recreation of a tattoo in a video game, if the court’s ruling were to stand, it could effectively prevent anyone with a tattoo from appearing on film or even in a photo posted on social media without a jury weighing in on fair use.

While it’s true that Take-Two’s video games don’t feature a precise photographic likeness of Orton, they were designed to realistically capture his identity. In a pretrial declaration, one of the WWE 2K developers described the process used to achieve this realism:

The defendants’ arguments would have been even stronger in a case involving the claimed infringement of a photographic likeness of Orton, but it’s really just a matter of degree. Orton’s likeness, tattoo and all, could have just as easily been depicted in a graphic novel, comic book or other expressive work. Photographic likeness or not, the important thing is that the use of the tattoo is necessary to accurately reflect Orton’s real-life appearance. Insofar as a tattoo, once inked, becomes part of a person’s identity, it should be subject to the same laws governing any other uses of identity, which include protections under the First Amendment.

If this type of derivative work isn’t protected under an implied license, or as a de minimis or fair use, it would fundamentally disrupt settled expectations of the tattoo and entertainment industries. Tattoo clients—especially celebrities—would need to insist on obtaining a copyright assignment or express written license from tattoo artists whenever they get inked. Without these rights, the producers of motion pictures, television shows, and even news programs would be required to get permission for the use of any design that’s visible on the body of anyone appearing on screen.

The same is true of photographs. For example, here’s a picture I took of Dua Lipa which captures the tattoo on the underside of her right arm:

The incidental reproduction of the tattoo as part of the photograph should be upheld without having to prove fair use to a jury.

The Bottom Line

Obviously, a $3,750 damages award wasn’t what Alexander was hoping for. Her attorney Anthony Simon told Law360 that “The case wasn’t about damages. It was about vindicating the rights of little tattoo artists who have inked famous people all over the country.” At the same time, Alexander’s lawyer reportedly suggested that the jurors award Alexander $2 for each copy of WWE 2K sold, which would come out to about $20 million. They declined to do that here, but there’s no saying what a future jury will do. Simon himself predicted that the verdict could “open the floodgate” for future tattoo litigation.

Case in point: There’s already another video game tattoo lawsuit pending against Take-Two in the Northern District of Ohio. That case involves tattoos featured on the likenesses of NBA players, and the court has (like Judge Yandle here) denied the defendants’ motion for summary judgment.

When I first wrote about Alexander after the court denied summary judgment to defendants, I wrote “Do I think a jury will understand what’s at stake here? I think so. I certainly hope so. But as the gatekeeper of the court, the trial judge should have never put us in a position of having to find out.”

To be honest, I don’t know if the jury understood what was at stake. What I do know is that the role of the district court is to indeed serve as the gatekeeper on issues of law. The court simply didn’t do that here, and this is what we’re left with. That said, I don’t expect the trial court’s summary judgment decision or the jury’s verdict to be the last word on this subject. Here’s hoping the Seventh Circuit gets it right on appeal.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. You can use the comment section below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here are the thoughts of a few folks who have already weighed in publicly on Twitter: