In a first-of-its-kind lawsuit, Columbia Pictures claims that a writer’s use of a loan-out company prevents him from terminating the studio’s rights in the film Bad Boys.

It’s finally happened. A major motion picture studio has filed a lawsuit challenging the termination of a copyright assignment made by a writer’s loan-out company. Given the near-universal use of loan-outs among Hollywood screenwriters, I’m frankly amazed that it’s taken so long. But here we are, and to quote our current president, “This is a Big F—ing Deal.”

UPDATE—June 14, 2024—Another copyright termination lawsuit bites the dust, as Columbia Pictures has dismissed its case against the writers of the story on which the Bad Boys film franchise was based, following a settlement between the parties.

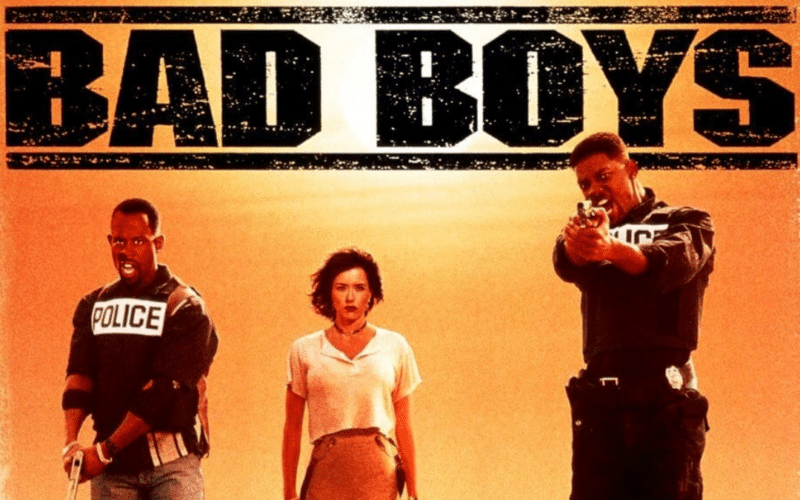

The complaint (read here) was filed on Friday by Sony’s Columbia Pictures against George Gallo and Robert Israel, who co-wrote a story called “Bulletproof Hearts” on which the first film in the comedy franchise Bad Boys was based. In a 1985 assignment, Gallo represented that he wrote the story as an employee-for-hire of his loan-out company, Sweet Revenge Productions, which is also named as a defendant. The studio is asking the court to declare that a copyright termination notice served by Gallo and Israel in 2020 is invalid because transfers of works made for hire aren’t subject to termination under section 203(a) of the Copyright Act.

Gallo apparently disputes the work-for-hire characterization, which may put him in the unenviable position of having to explain to a judge that he didn’t really write his story as an employee of Sweet Revenge and that the company was merely used to take advantage of favorable tax treatment and other benefits afforded to loan-out corporations. Hundreds of other writers fortunate enough to have penned material still valuable after 35 years may find themselves in a similar quandary when they try to exercise copyright termination rights.

Legal Fiction Meets Cold Reality

As I’ve written before, loan-out companies are a legal fiction, albeit one that’s perfectly valid and incredibly common in the entertainment industry. Creative artists are “employed” by companies they wholly own, with their services then “loaned out” to studios, streamers, and other hiring parties. This structure provides artists with a number of benefits, most of them involving favorable tax treatment, along with access to qualified pension, profit-sharing, and employer medical reimbursement plans.

But these benefits don’t come for free. In order to ensure that the loan-out arrangement isn’t just a big tax evasion scheme, the IRS and courts have insisted that the artist render services as an employee of the loan-out corporation, which needs to maintain the right to direct or control the artist in some meaningful sense.

To keep their clients on the good side of taxing authorities, entertainment lawyers typically draft loan-out agreements so as to leave no question that the artist is, in fact, employed by the loan-out. These contracts often expressly provide that the results and proceeds of an artist’s services are “works made for hire” on behalf of the corporation, which means that the loan-out is deemed the legal “author” of the artist’s work from inception. If the artist-employee later tries to distance himself from this contractual language, there’s a risk that the loan-out will be seen as a sham, possibly subjecting the artist to a host of adverse tax consequences and penalties.

Columbia Pictures’ Complaint

This brings us to the new lawsuit, although the story really begins back in the summer of 1985. That’s when Gallo and Israel wrote their story “Bulletproof Hearts.” Later that year, Gallo’s loan-out, Sweet Revenge, along with Israel, sold the story to Paramount Pictures.

The Transfers

In the parties’ agreement (read here), Gallo and Sweet Revenge expressly represented and warranted that Gallo “created and/or wrote the Story as an employee-for-hire” of Sweet Revenge and that the story “constitutes a work-made-for-hire pursuant to the United States Copyright Laws.” Gallo signed the agreement on behalf of Sweet Revenge as its President, as well as an addendum in which he agreed to be bound in his personal capacity.

In the early 1990s, Paramount transferred its rights to “Bulletproof Hearts” to Disney’s Hollywood Pictures. (Fun fact not mentioned in the complaint: producer Jerry Bruckheimer’s original plan was for the story to serve as a buddy vehicle for Saturday Night Live alums Dana Carvey and Jon Lovitz. Carvey and Lovitz ended up making Trapped in Paradise instead, which Gallo also wrote and directed. That film grossed just $6 million at the box office, effectively killing Dana Carvey’s film career as a leading man.)

By 1995, the “Bulletproof Hearts” rights had landed at Sony’s Columbia Pictures, which finally released Bad Boys in April 1995—10 years after the underlying story was first sold to Paramount. The film proved to be a star turn for Will Smith and Martin Lawrence and was followed by two sequels. In January 2020, The Hollywood Reporter reported that a fourth installment of the Bad Boys franchise was in development.

The Termination Notices

Following the announcement of a Bad Boys reboot, Gallo and Israel served Columbia with two copyright termination notices in June 2020, 35 years after their initial copyright transfer. The first notice (read here) purports to terminate the assignment of the copyright in the story “Bulletproof Hearts” to Paramount effective June 27, 2022.

The second termination notice (read here) is a head-scratcher. It purports to terminate a September 23, 1985, grant by George Gallo of his rights in the story “Bulletproof Hearts” to his loan-out company Sweet Revenge. That September 23 date just so happens to be one day before the effective date of Sweet Revenge’s September 24 agreement with Paramount—an agreement that makes no mention of any prior grant from Gallo to Sweet Revenge. Importantly, a Gallo-Sweet Revenge assignment would be unnecessary if Sweet Revenge’s representation that Gallo wrote the story as an employee-for-hire were in fact true. Sweet Revenge would already own the story by operation of law.

According to Columbia’s complaint, the studio requested a copy of the mysterious assignment from Gallo to Sweet Revenge, but was ignored for over two years. Columbia finally got a copy in late 2022, but unfortunately doesn’t include it with its initial court filing. Among other things, it’s unclear whether the assignment was actually made in 1985 or was instead executed after the fact. (My money’s on the latter.)

My Take

The September 23, 1985, assignment from Gallo to Sweet Revenge is strange for a number of reasons. Most obviously, it’s fundamentally inconsistent with the work-for-hire representations that Gallo and Sweet Revenge made when they sold the story to Paramount just a day later. It’s also at odds with the way loan-out companies typically function. Writers are treated as employees of their loan-outs, which means that works created within the course and scope of their employment are automatically works for hire under the 1976 Copyright Act. No assignment to the loan-out would be necessary unless the story were somehow written outside the scope of the writer’s employment. While this might be true in the case of a story written by an actor or director who isn’t typically in the business of writing, such an arrangement would probably be viewed with skepticism by taxing authorities if the artist’s career normally involves the creation of screenplays.

A screenwriter might be able to argue that the employer-employee relationship set forth in a loan-out arrangement, while sufficient to satisfy the tax code, doesn’t satisfy the multi-factor agency test used by the U.S. Supreme Court to determine whether a work has been created within the scope of an employment relationship. It’s also possible that a particularly forward-thinking writer would try to fashion his 1980s loan-out arrangement to preserve future statutory termination rights.

But it’s hard to see how Gallo will be able to credibly argue that he wrote “Bulletproof Hearts” outside the scope of his loan-out relationship with Sweet Revenge when he specifically represented and warranted that the story was created as a work made for hire on behalf of his loan-out the very next day. Not surprisingly, Columbia’s complaint also includes a claim for breach of contract in the event Gallo’s termination notice is deemed effective.

What About Bob?

Where does all of this leave Robert Israel, the other co-author of “Bulletproof Hearts?” Israel’s assignment doesn’t appear to be hampered by the loan-out issue, but his attempt to recapture an interest in the story may still suffer by virtue of his association with Gallo. That’s because, under Copyright Act section 203(a), a grant by two or more authors of a joint work can only be effected by a majority of the authors who executed the grant.

If the co-authors of “Bulletproof Hearts” are actually Israel and Sweet Revenge (as opposed to Israel and Gallo as individuals), then only Israel would possess a termination right. But Israel alone wouldn’t constitute a majority of the authors who executed the grant, which may mean he’s out of luck unless the court were to somehow interpret section 203(a)’s majority provision as only applying to natural persons. (I’m unaware of any prior cases dealing with this issue.)

A Dearth of Precedents

Ultimately, a district court judge is going to have to tackle some particularly thorny copyright termination issues when deciding this case, only a few of which I’ve highlighted in this article. And unfortunately, the court won’t have much precedent to rely on. I’m only aware of two other cases that have even touched upon the loan-out issues presented here.

Waite v. UMG Recordings, Inc.

The first is one I’ve written about before, Waite v. UMG Recordings, Inc. In that case, Southern District of New York Judge Kaplan held that musician John Waite couldn’t terminate copyright transfers made by his loan-out companies. But in Waite, there was no attempt to terminate an underlying prior grant to Waite’s loan-out, nor did the court reach the issue of whether Waite and his loan-out companies actually had an employer-employee relationship. Notably, in briefly responding to Waite’s argument that his loan-out company was only a “tax-planning device,” the court cautioned that “people cannot use a corporate structure for some purposes—e.g. taking advantage of tax benefits—and then disavow it for others.”

Clancy v. Jack Ryan Enterprises

The second, Clancy v. Jack Ryan Enterprises, involved a massive dispute between the widow of author Tom Clancy and two business entities that Clancy co-owned with his first wife and their four children. Judge Hollander from the District of Maryland found a genuine dispute of material fact as to whether Clancy was an employee or an independent contractor of his businesses under the Supreme Court’s Reid test, notwithstanding Clancy’s representation in certain book publishing agreements that the books were works for hire. Notably, Clancy’s widow was forced to argue that his entities were mere “shells” and not “true businesses”—positions probably made easier by the fact that Clancy was deceased.

The Bottom Line

It will be interesting to see if Gallo is willing to potentially sacrifice the favorable tax treatment afforded by his loan-out corporation (and possibly subject himself to IRS penalties) in an attempt to preserve his putative copyright termination rights. But having his cake and eating it too may not be a viable option—he’s either an employee of his loan-out or he isn’t, and the elements that a loan-out needs to satisfy in order to withstand IRS scrutiny happen to be the very factors that weigh in favor of an employment relationship for copyright purposes.

Whatever the outcome, this one’s going to be fascinating to watch. As always, if you have opinions on the case, I’d love to hear them. You can use the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of Columbia Pictures’ complaint, hot off the presses.

6 comments

Ho boy this is going to get fun. I can only imagine how delighted the studios and record companies were to see the ascendance of loan-out companies.

Excellent analysis, Aaron. I have questions.

1.

When the court told John Waite he can’t use the corporate form for one purpose and disavow it for another, I’m not sure that’s right. It’s inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s CCNV v. Reid opinion, which considers federal tax status just one of the many factors in determining whether someone is a work for hire under copyright law. They’re not one and the same.

2. Consider the reverse. When the studios argued Victor Miller wrote his script as an employee within the scope of his employment, were they concerned about the tax consequences?

Hi Mark,

You’re right that tax status is just one of the CCNV factors, but empirically, tax treatment and the provision of employee benefits turn out to be the most important factors. The bigger issue is that when you look at typical employment agreements between artists and their loan outs, they’re filled with language that checks almost all of the CCNV boxes, not to mention express WFH language. And unless I’m misunderstanding your question, the studios don’t face the same quandary in arguing that an artist’s corporate form should be disregarded, because they aren’t the ones who’d be on the hook with the IRS.

Perhaps it’s true they do everything to make sure they’re an employee.

On my second question, I meant when they’re no loan out company, but the party fighting claiming termination is claiming the terminator was an employee.

Your comment about loan out employment agreements is not entirely accurate. Many agreements allow the employee to create a work outside of the WFH context and hold individual title. This allows the individual to get a step up in basis upon death..

That fact may not save Gallo, based on his own statements, but that’s a different matter.

Hi Greg – you’re correct that loan-out agreements may be structured so that a writer’s work product is created outside the scope of employment. This may allow the writer to preserve termination rights (although this hasn’t yet been tested in the courts). The bigger potential concern is with the IRS – if the writer is ostensibly employed to write, and yet everything he writes is outside the scope of employment, what benefit is the “employer” actually getting?