A new complaint involving competing pooping puppy puzzles shows why drawing the line between ideas and expression can be difficult business.

2023 is shaping up to be a year of crappy IP lawsuits. In January, BMG sued over a glitter-pooping unicorn doll that sings “My Poops” to the tune of the Black Eyed Peas pop-rap hit “My Humps.” Then in June, the Supreme Court decided a trademark dispute sparked by a poop-themed dog toy that resembles a Jack Daniel’s liquor bottle. But number 1 when it comes to number 2 is a new copyright infringement lawsuit filed this week over a jigsaw puzzle called “101 Pooping Puppies.”

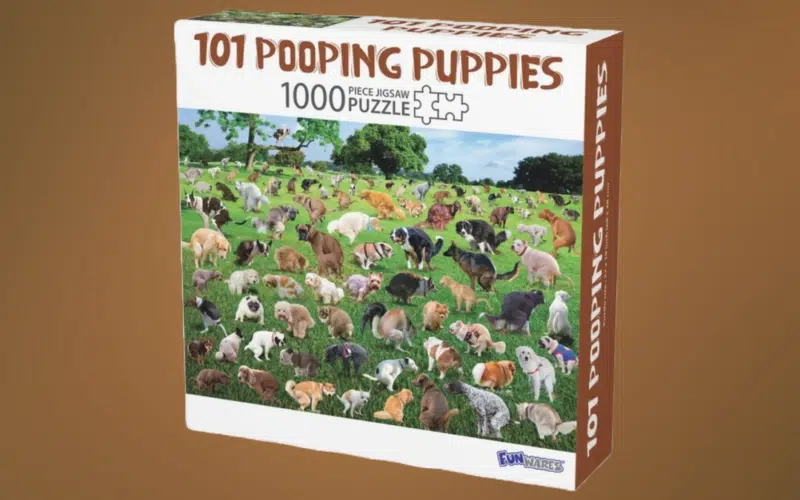

The plaintiff is UT Brands, which does business under the name Funwares. According to the complaint (read here), “101 Pooping Puppies” is currently the top-selling jigsaw puzzle on Amazon, which seems incredible to me. If I wanted to stare at dog poop for three hours, I’d watch an Oakland A’s game. But these puzzles are apparently popular gag gifts, and UT Brands’ success soon spurred competitors to enter the pooping puppies puzzle market.

One of these competitors is defendant Daniel O’Donnell, who runs a company called Better Me Games. O’Donnell sells his own Pooping Puppies puzzle that the plaintiff alleges is “substantially similar, both objectively and intrinsically” to its original. UT Brands also claims that the defendant uses “search optimization tactics to ensure that Defendant’s Infringing Product appears in searches near UT Brands’ Copyrighted Product.”

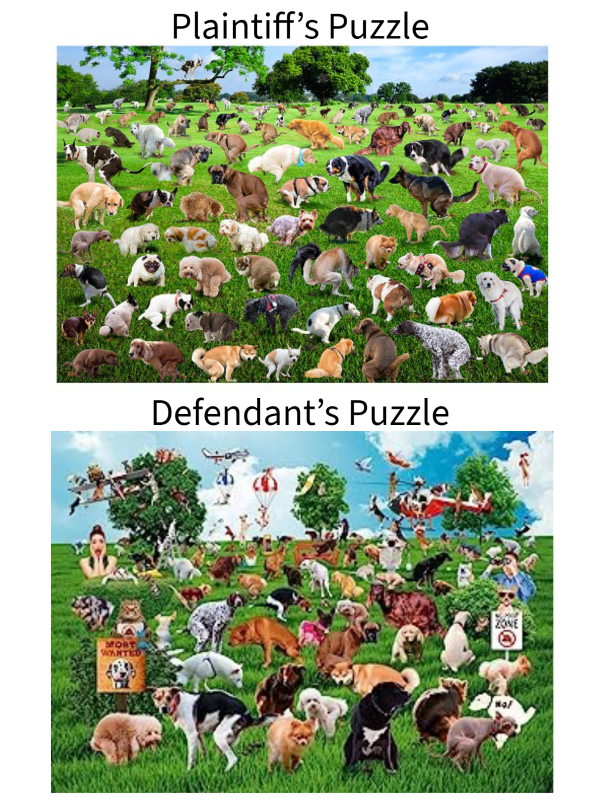

The complaint doesn’t include much in the way of detail, but here’s a closer look at the products so you can compare them for yourself:

At first glance, the two images share a lot in common, not only with respect to their content but in their perspective and composition as well. Both use high horizon lines that draw the viewer’s focus to a large grassy field in the foreground, and they feature a similar arrangement of puppies within the frame. However, a closer inspection reveals that all of the puppy photographs are different, and the inclusion of puppies in airplanes and parachutes along with the use of signs and other humorous elements give the defendant’s image a more whimsical feel than the plaintiff’s.

So who wins? It’s likely going to come down to where the judge decides to draw the line between ideas and expression.

The Idea-Expression Dichotomy

While the subject matter is silly, the pooping puppies case provides a pretty good example of the idea-expression dichotomy. Unfortunately, this widely-taught legal principle isn’t actually very helpful in predicting how copyright cases will be decided in the real world.

As a refresher, copyright protects the expression of an idea, but not the idea itself. That’s to help ensure a proper balance between innovation and competition. In practice, the distinction between “ideas” and “expression” can be incredibly difficult to draw. As Judge Learned Hand once wrote, “Obviously, no principle can be stated as to when an imitator has gone beyond copying the ‘idea,’ and has borrowed its ‘expression.’ Decisions must therefore inevitably be ad hoc.”

It’s not merely that drawing a distinction between ideas and expression is fact-specific; it’s often outcome-driven as well. In other words, if the result in a particular case is that a work is infringing, similarities are deemed to be in protectable expression. If the result is no infringement, similarities are dismissed as mere ideas. At the very least, the difference between ideas and expression is one of degree, and reasonable minds can (but shouldn’t always!) differ.

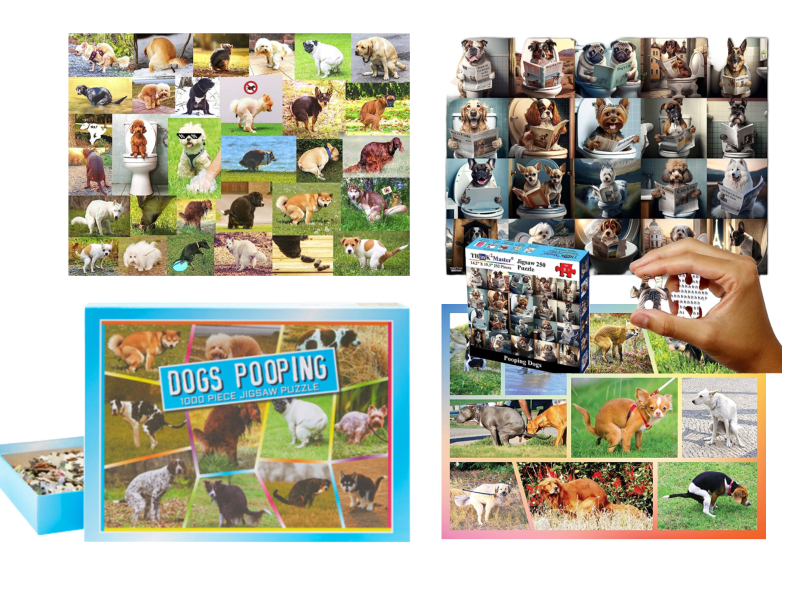

Going back to the pooping puppies, if the “idea” is defined in very broad terms—a puzzle depicting dogs pooping—there are lots of different ways to express this idea. Here are several more examples from a surprisingly crowded field:

Notice that all of the puzzles above feature a collection of individual dog images. But what if the “idea” is defined more narrowly—a picture of dogs all pooping on the same grassy field? At this level of abstraction, the range of creative choices is more restricted. For example, the field will necessarily need to be depicted from a perspective that can accommodate all of the individual dogs.

The field on the left won’t work at all. There’s not enough room for all the dogs, let alone all the poop. The horizon line needs to be higher so that there’s more grass and less sky. Toilet Etiquette 101 dictates that the dogs need to be spread out as well. If we exclude these similarities in perspective and composition as unprotectable, what’s left may not be all that substantial.

A Matter of Perspective

As another example, consider Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures. This case involved an infringement claim brought by artist Saul Steinberg, who drew the image for The New Yorker magazine cover on the left. Steinberg claimed his piece, called View of the World from 9th Avenue, was infringed by the movie poster for the Robin Williams film Moscow on the Hudson.

Southern District of New York Judge Louis Stanton granted summary judgment for the plaintiff, which is pretty unusual. Among other things, he described the common perspective in the two pieces as “a bird’s eye view across the edge of Manhattan and a river bordering New York City to the world beyond.” The judge noted that both artists “chose a vantage point that looks directly down a wide two-way cross street that intersects two avenues before reaching a river,” and found this to be protectable expression. That determination was driven in large part by the judge’s observation that, in real life, most New York City cross streets are one-way.

This surely is evidence of copying (what some courts refer to as “probative similarity”) but it doesn’t seem particularly relevant to a determination of whether the copying was of protectable expression. The same is true for the spiky block print used for names of the streets, which was a hallmark of Steinberg’s art but isn’t protectable under copyright law. While there are enough actual expressive similarities between the works to justify the court’s decision, the idea/expression determination is really just a conclusion as opposed to an explanation.

The Bottom Line

It may sound jaded, but the outcome of the pooping puppies case will depend on which side does a better job of navigating the idea-expression spectrum and, ultimately, on the particular aesthetic value judgments of whoever’s deciding the case. On balance, I think the plaintiff has better odds of prevailing, but so long as the defendant gets a decent lawyer, it shouldn’t be a totally poop-free walk in the dog park.

So what do you think? Are you bowled over, or should the pooping puppies lawsuit be flushed down the toilet? Let me know in the comments below or @copyrightately on social media. That now includes Threads, because of course we all need yet another social media account.

4 comments

Did you notice that there seems to be copyright infringement of the photo on the bottom right of the crowded field puzzles and the beagle in the middle of the defendant’s puzzle? Weird.

Hmm. I couldn’t find that, but I may not be the best judge. Some of these dogs look like foxes to me.

Aaron, where can i see the outcome of this lawsuit?

I’ll post an update on this page if there’s a ruling – the case was just filed, so it may be awhile.