Is Rick Astley’s right of publicity claim against Yung Gravy for “vocal impersonation” on a collision course with the federal Copyright Act?

British singer Rick Astley is best known for “Never Gonna Give You Up,” a song people voluntarily listened to in 1987 and were tricked into listening to in 2007. Decide for yourself which is worse, although I should point out that in 1990 the song was part of a psychological torture campaign to force Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega to surrender and face charges for drug trafficking. It worked.

Already a fixture on the pop charts and in the world of bait-and-switch hyperlinks, Astley is now looking to make history yet again, this time with a new lawsuit that may put a damper on the music industry’s latest nostalgia kick.

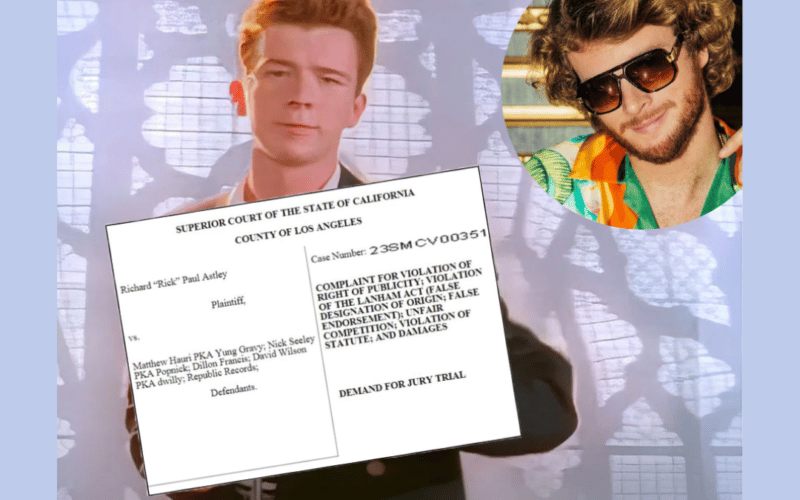

Astley v. Matthew Hauri, pka Yung Gravy

On Friday, Astley filed a right of publicity complaint against Yung Gravy (real name Matthew Hauri), an American rapper you probably don’t want to let within 100 feet of your mom. Astley is claiming that Gravy violated his right of publicity by using a singer (defendant Nick Seeley, pka Popnick) to imitate Astley’s “signature voice” from “Never Gonna Give You Up” on Gravy’s 2022 hit “Betty (Get Money).”

Here’s a link to Astley’s complaint, which I’m guessing half of you won’t click because you think it’s a rickroll. Don’t worry, it’s legit. (To all the naysayers, I’ll remind you that Copyright Lately is considered a scholarly publication by several of this nation’s law schools, at least one of which is still accredited.)

What makes Astley’s case interesting is that Gravy and his record label obtained the appropriate copyright license to recreate the melody and lyrics from “Never Gonna Give You Up” (which Astley didn’t write and doesn’t control) for “Betty (Get Money).”

But according to Astley’s complaint, “A license to use the original underlying musical composition does not authorize the stealing of the artist’s voice in the original recording.” Gravy and his team couldn’t get a license to sample the master recording. “So, instead, they resorted to theft of Mr. Astley’s voice without a license and without agreement.”

Astley’s complaint quotes an August 2022 interview with Billboard in which Yung Gravy admits that “we basically remade the whole song” with “a different singer and instruments, but it was all really close because it makes it easier legally.”

Before diving into whether the alleged imitation of Astley’s voice was in fact legal, there are a few concepts that are important to know in order to properly understand the case.

One Song, Two Copyrights

First, as I’ve explained before, every piece of recorded music is actually comprised of two different copyrights. There’s a copyright in the underlying composition, which protects the lyrics and musical arrangement of a song. There’s also a separate copyright in a particular sound recording of that song as performed by a recording artist. When you listen to music on the radio or a streaming service, you’re technically hearing both the composition as well as the sound recording of that composition.

According to Astley’s complaint, he doesn’t have any rights in the underlying “Never Gonna Give You Up” composition, but does claim a partial interest in the sound recording containing his performance. The defendants obtained a license to use the former, but not the latter.

Samples vs. Interpolations

Once you know the distinction between sound recordings and compositions, you’ll also understand the difference between samples and interpolations. Sampling involves taking part of an existing sound recording and incorporating it into a new work. When a sound recording sample incorporates an underlying composition (as is often the case), licenses to use both copyrights are typically required. Some famous samples include Eminem’s lift of Dada’s “Thank You” in “Stan” and M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes,” which samples the opening riff from “Straight to Hell” by the Clash.

An interpolation, on the other hand, involves taking part of an existing musical composition (as opposed to a sound recording) and incorporating it into a new work. Interpolation is sometimes confused with sampling, but the difference is that interpolations don’t involve the use of any actual sounds from a preexisting recording. Instead, new audio is recorded. A couple of famous interpolations are Ariana Grande’s use of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things” in “7 Rings” and Taylor Swift’s interpolation of Right Said Fred’s “I’m Too Sexy” in “Look What You Made Me Do.”

Interpolations (Get Money)

Interpolations are big business, especially for many of the venture-capital backed companies looking to recoup some of the hundreds of millions of dollars they’ve spent acquiring music publishing rights from the likes of Paul Simon, Stevie Nicks, and Bob Dylan.

While not mentioned in Astley’s complaint, the entity that owns the publishing rights to “Never Gonna Give You Up” is Primary Wave, a prolific purchaser of publishing rights to catalogs tied to Bob Marley, Nirvana, and Prince. Primary Wave bought the rights to “Never Gonna Give You Up” as part of songwriter Pete Waterman’s catalog.

In a story published in Billboard in September 2022, Primary Wave explained that the creation of “Betty (Get Money)” was part of a strategy the company has been working on for the past few years. Primary Wave has actively encouraged creatives, like Yung Gravy collaborator Popnick, to use melodies, lyrics and samples of the company’s catalog as a way of increasing the value of Primary Wave’s holdings “while easing the tedious licensing process for the music makers at the same time.”

Primary Wave licensed the right to use the “Never Gonna Give You Up” composition to Yung Gravy’s team, which allowed them to copy the lyrics and melody, but not to record the actual sounds from the sound recording.

Note that while Primary Wave has an indirect financial stake in “Betty (Get Money)” based on its ownership of Waterman’s piece of the song, the company isn’t named (or even mentioned) in Astley’s lawsuit.

Copyright Act Section 114(b) Permits “Soundalikes”

According to an informational circular published by the U.S. Copyright Office, “Permission from the copyright owner of a preexisting sound recording is not necessary when interpolating a musical work, regardless of how similar the new recording may be to an old recording. This is because, under U.S. copyright law, the exclusive rights in sound recordings do not extend to making independently recorded ‘soundalike’ recordings.”

The Copyright Office is referring to 17 U.S.C. § 114(b), a provision of the Copyright Act that limits the exclusive rights of the owner of a sound recording copyright to (1) the right to duplicate the “actual sounds” fixed in the recording, and (2) the right to prepare derivative works in which those actual sounds are “rearranged, remixed, or otherwise altered in sequence or quality.”

To leave no uncertainty as to the law’s intent and effect, the House Judiciary Committee Notes to Copyright Act section 114(b) state that “Mere imitation of a recorded performance would not constitute a copyright infringement even where one performer deliberately sets out to simulate another’s performance as exactly as possible.”

“The exclusive rights of the owner of copyright in a sound recording . . . do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that consists entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds, even though such sounds imitate or simulate those in the copyrighted sound recording.”

17 U.S.C. § 114(b).

You’ll notice that section 114(b) expressly states that the creation of soundalike recordings are not a violation of copyright law. But Astley isn’t suing for copyright infringement. Instead, he’s claiming that the imitation of his voice is a violation of California’s right of publicity law, which protects against the unauthorized use an individual’s name, image, likeness, voice and other attributes of the person’s identity.

Midler v. Ford Motor Co.

Astley’s lawyers assert that in order to use an artist’s voice, “the creators of a new recording need a license to copy the actual sounds of the voice from the sound recording.” But here, the defendants didn’t use Astley’s voice; they imitated it. That brings us to the Ninth Circuit’s 1988 opinion in Midler v. Ford Motor Co., a case repeatedly cited in Astley’s complaint. Midler held that California’s common law right of publicity can be violated “when a distinctive voice of a professional singer is widely known and is deliberately imitated in order to sell a product.”

The facts of Midler are pretty straightforward. Ford’s ad agency licensed the musical composition “Do You Wanna Dance” for use in a Mercury Sable commercial. The song had been made famous by Bette Midler, but Midler’s representatives wouldn’t license the sound recording featuring Midler’s voice. So the ad agency hired one of Midler’s former backup singers, Ula Hedwig, and told her to “sound as much as possible like the Bette Midler record.” After the commercial featuring Hedwig aired, a number of people told Midler that it “sounded exactly” like her record of “Do You Want to Dance.”

The Ninth Circuit held that Midler couldn’t state a claim under California’s right of publicity statute, Civil Code section 3344, because the “voice” used in the commercial was Hedwig’s, not Midler’s. The court did, however, permit Midler to pursue a right of publicity claim under California common law. The common law right of publicity complements the state statute and more broadly protects against the misappropriation of a person’s identity, including vocal performances. For the Ninth Circuit, to impersonate Midler’s distinctive voice was “to pirate her identity.” And so the concept of “vocal appropriation” was born.

The First Amendment

The principal factual difference between Astley’s case and Midler’s is that Astley’s voice was not imitated in a commercial advertisement for an unrelated product. Astley’s lawyers look to be trying to expand the doctrine to encompass the reproduction and distribution of Astley’s voice in an expressive work.

This is going to be a tough sell, as courts routinely recognize that songs, books, motion pictures and other works of creative expression receive greater free speech protection under the First Amendment than commercial speech. This is why filmmakers are able to produce biopics about celebrities and other notables (and actors can imitate those individuals) without running afoul of the right of publicity.

The Midler court itself briefly acknowledged that the First Amendment “protects much of what the media do in the reproduction of likenesses or sounds,” but didn’t expand on its discussion, presumably because the alleged violation was the use of a soundalike in a car commercial. That’s not the case with “Betty (Get Money),” which is a quintessential expressive work. (Well, maybe not a quintessential expressive work, but it’s an expressive work nonetheless.)

Copyright Preemption

As I discussed earlier, under section 114(b) of the Copyright Act, the mere imitation of a recorded performance won’t give rise to a copyright infringement claim, even if the creator sets out to simulate another’s performance as exactly as possible.

The 1976 Copyright Act created a unified federal copyright system, which regulates all copyright law in the United States. To achieve uniformity, federal law “preempts,” or overrides, conflicting state laws. Preemption comes in several different flavors, but I’m going to focus on two: express statutory preemption and implied conflict preemption.

The Copyright Act itself, in section 301, provides that a state cause of action is preempted if it creates rights that are (1) equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright in (2) works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression and come within the subject matter of copyright.

But even if the statutory requirements for express preemption under section 301 aren’t met, a state law can still be subject to a form of implied preemption known as “conflict preemption” if the state law poses an obstacle to the accomplishment of federal goals.

This raises the question: Are states permitted use right of publicity laws to prohibit soundalikes, even though the federal Copyright Act expressly allows it?

The Interplay Between Copyright Act Section 114(b) and the Right of Publicity

In Midler, the Ninth Circuit acknowledged Copyright Act section 114(b), and quoted from its legislative history: “Mere imitation of a recorded performance would not constitute a copyright infringement even where one performer deliberately sets out to simulate another’s performance as exactly as possible.”

But in the court’s view, Midler wasn’t seeking damages for Ford’s use of “Do You Wanna Dance,” and therefore her claim wasn’t preempted by federal law: “Midler does not seek damages for Ford’s use of ‘Do You Want to Dance,’ and thus her claim is not preempted by federal copyright law. A voice is not copyrightable. The sounds are not ‘fixed.’ What is put forward as protectible here is more personal than any work of authorship.”

The problem is that the Ninth Circuit never actually conducted any sort of preemption analysis in the case, whether under section 301 or under more general conflict preemption principles. Arguably, Midler wasn’t complaining about the use of her voice in an amorphous sense; her concern was over the imitation of a particular vocal performance captured on the “Do You Want to Dance” recording.

The Ninth Circuit missed another opportunity to properly analyze the interplay between section 114(b) and the right of publicity a few years later in Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc., which was also a case involving the use of a soundalike in a commercial. Unfortunately, the Waits decision only added to the confusion about preemption. In particular, the court purported to quote the legislative history of section 114(b) but instead mistakenly cited language pertaining to section 301, the Copyright Act’s express preemption provision. As in Midler, the Waits panel didn’t examine whether California’s right of publicity law, as applied to imitation sound recordings, conflicts with federal law or stands as an obstacle to achieving the objective of Congress.

Astley’s Right of Publicity Claim Should be Preempted By the Copyright Act

Under the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, Article VI, Paragraph 2, “the Laws of the United States . . . shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” This means that federal law takes precedence over state laws when the two laws are in conflict; when Congress has signaled an intent to “occupy the field” with respect to a certain type of federal legislation; or when Congress has passed an express preemption statute.

Statutory Preemption

Most courts that have considered preemption in the right of publicity context have focused on the Copyright Act’s express preemption provision, section 301. Recall that Midler and Waits held that the voice misappropriation claims in those cases didn’t come within the subject matter of copyright because the plaintiffs’ voices weren’t fixed in a tangible medium of expression.

Notwithstanding these precedents, there’s certainly an argument that express preemption under section 301 should apply here. Astley isn’t complaining about the use of his “voice” per se as much as he’s complaining about the imitation of a particular vocal performance on a particular sound recording of “Never Gonna Give You Up,” a performance that is fixed and does come within the subject matter of copyright. In addition, the acts giving rise to the right of publicity claim—the reproduction, distribution and performance of “Betty (Get Money)”—are the same acts that give rise to copyright infringement. Remember, Astley isn’t complaining that his voice was used for a commercial purpose, but rather in an expressive work. So arguably, the equivalency prong of section 301 applies as well.

Conflict Preemption

The strongest basis for preemption here is the implied “conflict” variety. It’s clear from the legislative history and the language of section 114(b) that Congress intended to allow imitation sound recordings under federal law. If California were to nevertheless restrict the reproduction and distribution of those recordings as a violation of the right of publicity, the state law would stand as an obstacle to the objectives of Congress. In other words, given that Congress has already spoken on this issue, Astley shouldn’t be able to pursue a state law claim based on activity that’s perfect legal, if not encouraged, under federal law.

Implications and The Bottom Line

The First Amendment and the Copyright Act should both prevent Rick Astley’s from prevailing on his right of publicity claim. Astley is also alleging a violation of the federal Lanham Act, which protects against consumer confusion. He may be able to state a valid claim for false endorsement if, as the complaint alleges, the defendants affirmatively and falsely represented that Astley endorsed “Betty (Get Money).” However, to the extent the claim is based on nothing more than the distribution of the song itself, it should be also barred by the First Amendment.

A ruling in Rick Astley’s favor in this case would effectively give a monopoly to the first performer of a song even if, as in Astley’s case, the singer didn’t write the song or own a copyright interest in the composition. Performers of cover songs would face legal risk if their voices sounded too similar to the first singer—or, for that matter, to any other singer who had previously performed the song—even if they complied with federal copyright law.

At the very least, Midler and Waits should be limited to right of publicity cases in which a vocal imitation is used to sell a product, as opposed to a claim seeking to prevent the dissemination of an expressive work.

Interestingly, Astley’s Lanham Act claim may also give the Ninth Circuit another opportunity to weigh in on conflict preemption. While Astley filed his lawsuit in state court in Los Angeles County, state and federal courts share concurrent jurisdiction under the Lanham Act, which means that Yung Gravy is permitted to remove the case to federal court. I suspect he’ll want to do that, as federal judges have greater experience in interpreting and applying federal law.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Let me know in the comments section below or hit me up on social media @copyrightlately. In the meantime, here’s a rickroll-free copy of Rick Astley’s new complaint.

6 comments

Excellent legal analysis. You managed to synthesize about five different legal textbooks into understandable explanation of a complicated matter arising from a rap record.

Music is a complicated business.

Kudos to Mr. Atsley for his music’s role in the capture of Manuel Noriega. Who knew?

Thanks so much Glenn! Really appreciate you reading and taking time to comment.

Best,

Aaron

You did a very very lovely job of breaking this case down, including where it will probably go and giving a great explanation of the law along the way. Thanks also for providing the complaint. Having successfully represented a plaintiff on a 3344 case some years ago (where the commerciality of the use was directly at issue), the reliance by plaintiffs on common law in their complaint was a bit baffling until I read your entire article. We’ll see what happens!

I suppose this is why at least one major publisher has language in their sync license template that prohibits imitating popular artists associated with the song.

You still couldn’t resist to make a rickroll in the article 😀 (“Cute Little Puppy Doing Cute thing”).

Did you write a follow-up, where does this matter stand now?

The case was settled in September, 2023, before any substantive pleadings were filed.