Breaking down Miramax’s copyright infringement lawsuit against Quentin Tarantino, a dispute about NFTs that isn’t really about NFTs.

Depending upon which side of the fence you’re sitting on, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are either the greatest economic innovation of the twenty-first century or the biggest grift since Lyle Lanley sold Springfield a monorail.

But love them or hate them, people can’t seem to stop talking about them. That’s why it was no surprise that the internet exploded this week when news broke that Miramax, the studio behind “Pulp Fiction,” had filed a complaint (read here) against the film’s writer/director Quentin Tarantino over his planned sale of scanned pages from the original “Pulp Fiction” screenplay as NFTs. Miramax claims, among other things, that the preparation and sale of these derivative works constitutes copyright infringement because the contractual rights Tarantino reserved in his 1993 agreement with Miramax don’t cover NFTs.

The breathless media reports soon followed. In its article on the case, “The Verge” stated that the lawsuit represents “one of the first legal tests of what an NFT actually is—or at the very least, whether it’s comparable to any of the options Tarantino reserved.” But while Miramax v. Tarantino is being billed as the first major legal dispute involving copyrights and NFTs, it really isn’t a dispute about NFTs. Frankly, it’s barely a dispute about copyrights.

NFTs Are Not a New Form of Media

Some of the confusion surrounding the lawsuit stems from a basic misunderstanding of what NFTs actually represent. Fundamentally, an NFT is just a transactional record and a link to a digital asset (often an image of artwork or a document) stored somewhere on the web. The NFT isn’t the image. It typically doesn’t even store the image. It simply contains information on where you can find the image and serves as proof of authenticity. Don’t get me wrong—a permanent chain of title record to a one-of-a-kind asset certainly has the potential to be valuable, but it’s important to recognize that NFTs have surprisingly little to do with what’s actually being bought and sold.

NFTs Are Not Copyrightable

The confusion only seems to increase when you introduce copyright into the mix. Again, NFTs are just an ownership record and a link to content. If they don’t embed an underlying asset, they likely don’t even fall within the subject matter of copyright. To be sure, the linked-to content can be the subject of copyright protection (and may or may not be infringing), but the fact that a piece of art or memorabilia is being sold “as an NFT” is more or less meaningless from a copyright perspective. While the Copyright Act gives the copyright owner the exclusive right to reproduce and distribute a digital file containing a copyrighted work, there’s no such thing as the “exclusive right to mint an NFT” as far as copyright law is concerned.

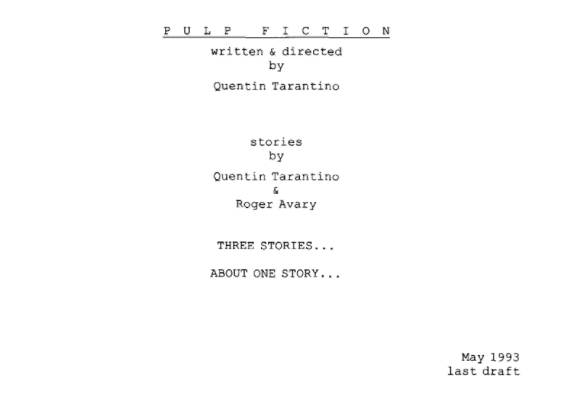

According to Miramax’s complaint, Tarantino’s counsel has represented that his planned collection consists of “7 NFTs, each containing a high-resolution digital scan of Quentin’s original handwritten screenplay pages for a single scene from his screenplay for Pulp Fiction.”

However, it’s unlikely that Tarantino’s NFTs will actually store any digital assets, let alone high-resolution screenplay scans. They would probably be too large. More likely, the NFTs are simply blockchain tokens that are associated with the digital files located somewhere “off-chain.” (One interesting angle to Tarantino’s sale is that the NFTs supposedly contain “secret” content that can only be unlocked and viewed by the owner.)

It’s also unlikely that the NFTs in and of themselves infringe anything owned by Miramax. The studio claims that the rights Tarantino reserved in his original agreement with Miramax don’t include NFTs. But that doesn’t seem particularly relevant, because the derivative works at issue are actually the screenplay scans, not the NFTs. If Tarantino assigned the exclusive right to sell images of his “Pulp Fiction” screenplay, he can’t sell them, whether as NFTs or otherwise. But if Tarantino did reserve those rights, it shouldn’t matter whether he’s selling them as NFTs or out of the back of a van.

NFTs are clearly the bright shiny object that’s driving the parties to court and attracting public interest in the lawsuit. But the less-shiny reality is that this is primarily a contract dispute—a fight about whether the publication rights Quentin Tarantino reserved in his agreement with Miramax include the right to sell digital screenplay scans. While Tarantino happens to be selling the scans as NFTs, the principal legal issue in the case will be whether he has the right to create and sell them at all. This will hinge on the meaning of Tarantino’s reserved “screenplay publication” rights.

While Miramax v. Tarantino is being billed as the first major legal dispute involving copyrights and NFTs, it really isn’t a dispute about NFTs. Frankly, it’s barely a dispute about copyrights.

Tarantino’s Reserved Rights

In the key contractual provision at issue, Tarantino granted Miramax all rights in the film “Pulp Fiction” and its elements, excluding certain defined “Reserved Rights” retained by Tarantino. These reserved rights include “soundtrack album, music publishing, live performance, print publication (including without limitation screenplay publication, ‘making of’ books, comic books and novelization, in audio and electronic formats as well, as applicable), interactive media, theatrical and television sequel and remake rights, and television series and spinoff rights.”

Based on his reserved screenplay publication rights, there’s no question that Tarantino is permitted to sell copies of the “Pulp Fiction” screenplay. You can buy one right now on Amazon. (A used copy will set you back $1.09; for reasons unknown, a new copy is going for $113.03. In the words of Vincent Vega, I don’t know if it’s worth $113.03, but it’s pretty good.)

The question is whether selling “1 of 1” digital scans of pages from the screenplay falls within Tarantino’s publication rights or, conversely, constitutes the sale of something else, such as merchandise, that he assigned to Miramax.

Is the Sale of a Single Item a “Publication”?

Determining whether Tarantino is acting within his contractual rights requires figuring out what the parties meant by the term “publication.” One potential way (though not the only way) to do this is by looking to the Copyright Act for guidance. This is, after all, supposed to be a copyright case.

Copyright law defines “publication” as the distribution of copies of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership or by rental, lease, or lending. Offering to distribute copies to a group of people for purposes of further distribution or public display also constitutes publication.

Of course, the draw for potential buyers is that Tarantino only plans to sell a single copy of each of the seven NFTs in his collection. Is the sale of a single work of original art considered to be a publication? Very curiously, the Copyright Office offers two diametrically opposed views on the subject. In its Circular 40, the Office explains that “A work of art that exists in only one copy, such as a painting or statue, is not regarded as published when the single existing copy is sold or offered for sale in the traditional way, such as through an art dealer, gallery, or auction house.”

However, in its Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, section 1905.1, the Copyright Office appears to take precisely the opposite position, stating that “If a work exists only in one copy – such as a painting embodied solely in a canvas – the work may be considered published if that copy is distributed to the public with the authorization of the copyright owner.” The Office even provides, as an example of publication, “Selling the original copy of a painting at an auction.” (It goes without saying that if anyone reading this works at the Copyright Office, I’d love to know what’s up. )

The contradiction in Copyright Office guidance is puzzling, and the only case I’m aware of that even touches on this issue goes back to 1904. In dicta, the court in Werckmeister v. American Lithographic Co. appears to suggest a distinction between the offer for sale of a single copy of a book (which would constitute a publication) and the exhibition for sale of a unique work of art (which would not). Putting aside that the Werckmeister opinion is based on an outdated version of the Copyright Act, it still doesn’t answer the question of whether Tarantino’s digital scans are more analogous to pages from a book or a collectible work of art.

Publication vs. Merchandise?

Even if we could draw a definitive conclusion from the Copyright Act, the interpretation of what constitutes “print publication” or “screenplay publication” doesn’t necessary hinge on the copyright law definition of the term “publication.” It’s really all a matter of what the parties intended, a question which is likely influenced by industry custom and practice at the time of contracting. (Of course, in 1993, people were barely buying and selling Beanie Babies, let alone digital screenplay scans.)

In its complaint, Miramax takes the position that the proposed sale of original script pages as an NFT is a “one-time transaction, which does not constitute publication.” This doesn’t strike me as a particularly compelling argument. Most sales are one time transactions, unless you happen to be one of those people who returns half-eaten birthday cakes to Costco. A stronger argument for Miramax would be that Tarantino’s entre into the collectibles market effectively constitutes merchandising, a right he previously granted to the studio. On the flip side, Tarantino’s best argument is that the sale of digital screenplay scans (along with promised commentary divulging the “secrets” of “Pulp Fiction”) is functionally no different than the sale of his screenplay in book form or an electronic “making of” book, both of which are product categories specifically reserved to Tarantino.

While the sale of NFTs is clearly what’s grabbing the headlines, it doesn’t appear particularly relevant to how the contract will be interpreted by a court.

Miramax v. Tarantino: The Bottom Line

While the contract interpretation issues are interesting in their own right, they really don’t seem to hinge on the fact that NFTs are involved. If Tarantino were to sell digital screenplay scans through a traditional auction, that type of sale would presumably generate the same legal issues—albeit not nearly the same level of interest.

The real importance of NFTs to this story has more to do with the staking of economic positions than legal ones. While Miramax’s complaint criticizes Tarantino for being “eager to cash in on the NFT boom,” this is because the studio doesn’t want him interfering with its own plans to cash in on the NFT boom. Like most legal disputes, it’s about the money. But regardless of how the case turns out, I don’t think it’s going to hinge on anything fundamentally unique about NFTs. NFTs just happen to be the shiny object du jour. The outcome probably won’t even have much significance beyond the contractual language between these two particular parties. Sorry to rain on your parade, but if my answers frighten you then you should cease asking scary questions.

Below is a copy of Miramax’s complaint against Tarantino (along with a full copy of his contract). As always, I’d love to know what you think. Let me know in the comments section underneath or on social media @copyrightlately—and have a Happy Thanksgiving!

View Fullscreen

1 comment

Thank you for this, but you shouldn’t let people insert shit like “Tarantino is arguably the GOAT”, in your article. 😉