A banana taped to a wall may qualify as art, but as a copyright infringement lawsuit it should have been left to rot.

A jury may need to decide whether one banana attached to a wall with a piece of duct tape infringes the copyright in another banana attached to a wall with a piece of duct tape—which pretty well sums up the state of the American judicial system in 2022.

The copyright lawsuit pits one conceptual artist, Los Angeles-based Joe Morford, against another, more well-known conceptual artist, Italian Maurizio Cattelan. Morford should have let his complaint remain conceptual, but he instead filed it in federal court. As regular readers of Copyright Lately already know, I’m a big fan of bananas and an even a bigger fan of duct tape. So I decided to do a deep dive into the court’s file and can confirm that the case is just as bananas as it sounds.

A Tale of Two Bananas

In some ways, it’s only fitting that Cattelan finds himself defending an absurd copyright infringement lawsuit. After all, it was Cattelan who was able to convince the art world not only that an ordinary grocery store banana and some household duct tape could constitute art, but that said art was worth up to $150,000.

Cattelan called his exhibit Comedian, which he displayed in late 2019 at Art Basel in Miami Beach. He sold three versions of the artwork for a total of nearly four hundred thousand dollars before enormous selfie-seeking monkeys crowds forced him to split early. One couple who spent $120,000 on Cattelan’s piece conceded that they were “acutely aware of the blatant absurdity of the fact that Comedian is an otherwise inexpensive and perishable piece of produce and a couple of inches of duct tape.” I didn’t catch the last part of the interview, but I’m assuming it was something to the effect of, “But our Scrooge McDuck-sized swimming pool can’t hold any more gold coins, so here we are.”

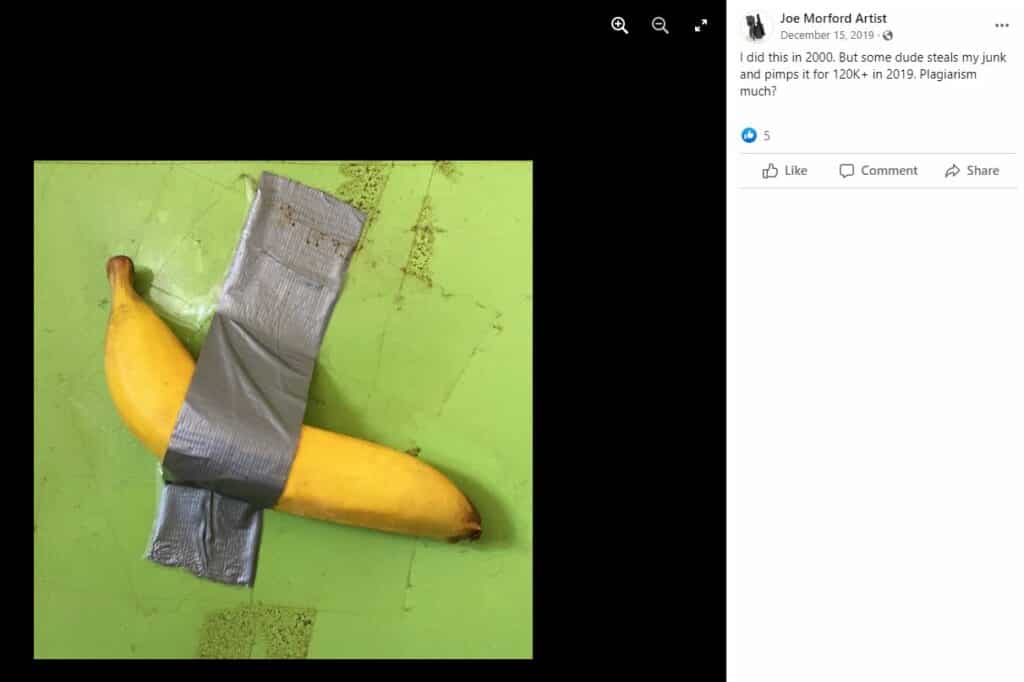

Other conceptual artists seeing Cattelan’s success no doubt asked themselves, “Why didn’t I do that?” But Morford said, “Hey, I did do that!” In a December 2019 social media post made shortly after the Art Basel exhibition, Morford proclaimed to his Facebook followers: “I did this in 2000. But some dude steals my junk and pimps it for 120k+ in 2019. Plagiarism much?”

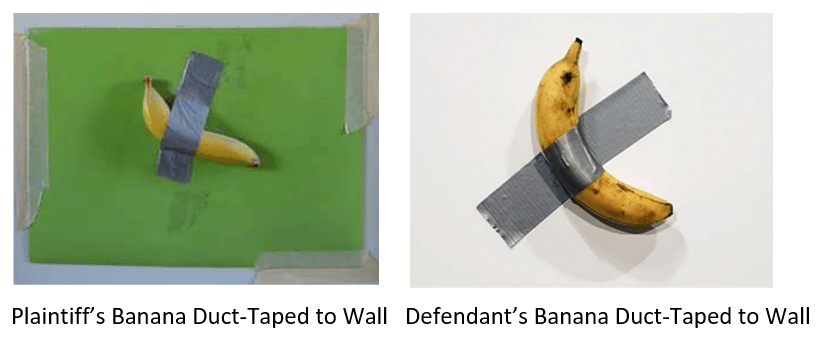

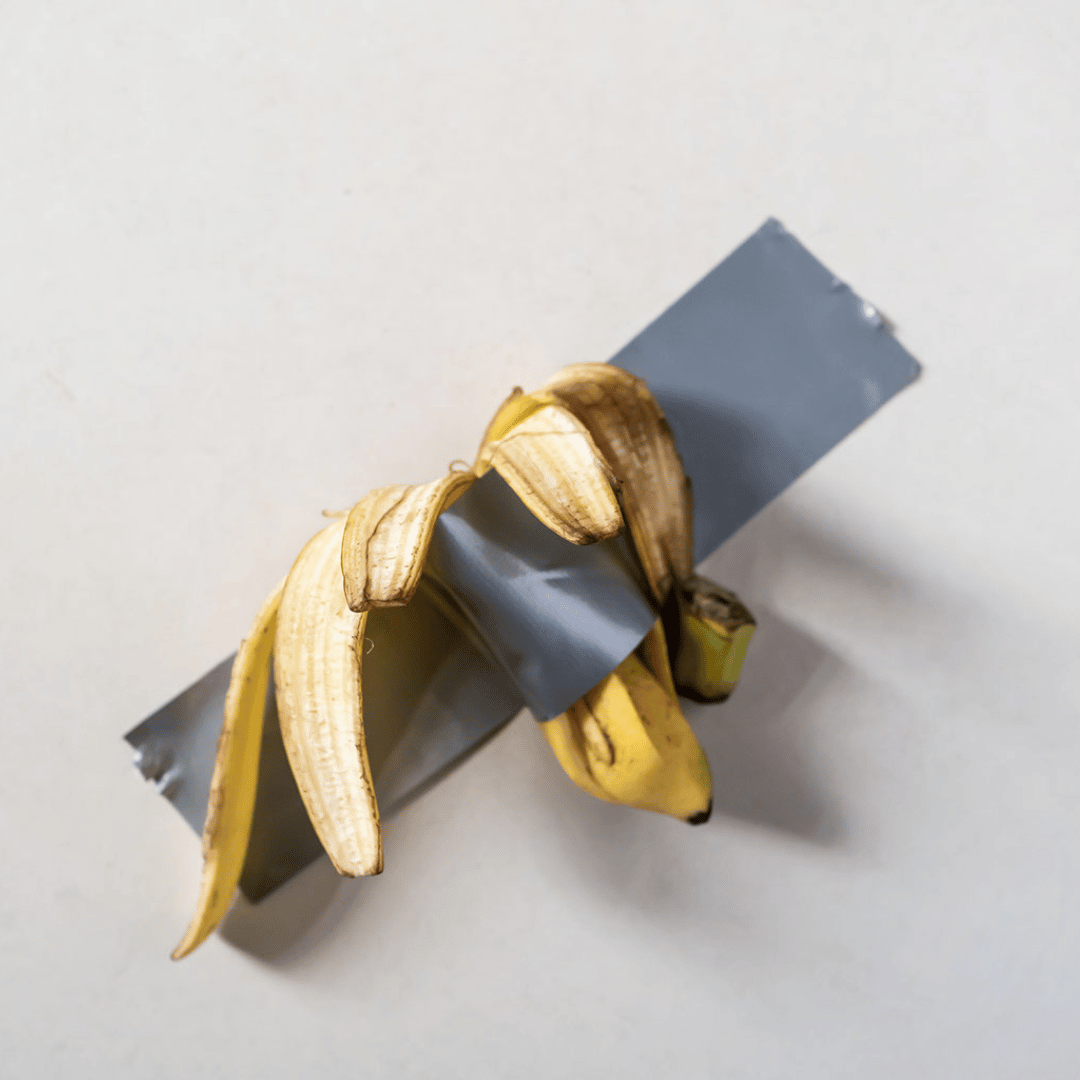

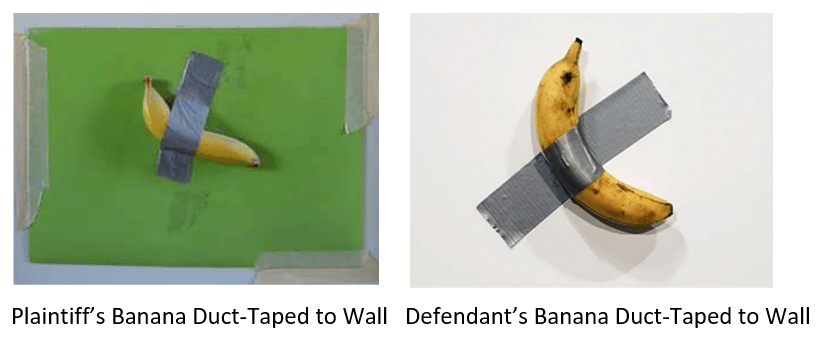

If you look closely at Morford’s image, it’s clear that the banana in his artwork is artificial. The banana isn’t attached to a wall, but to a green sheet of construction paper that appears to have been run over by a BMX bike after a trail ride. There’s also some clear tape used to hold the duct tape because, why not?

Morford v. Cattelan

Is it possible that two of the billions of fruit and tape-loving citizens of this planet could independently decide to place a piece of silver duct tape on a banana and then laugh at all of their sucker friends working office jobs? Of course not, so Morford proceeded to file a copyright infringement lawsuit against Cattelan in the Southern District of Florida, which encompasses Miami.

The Complaint

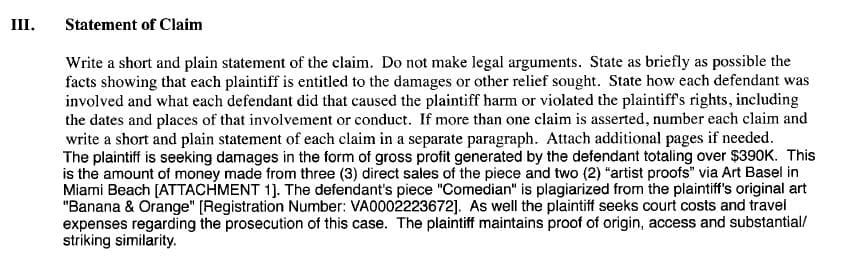

Morford is representing himself, so he used a form complaint to set forth his allegations against Cattelan. The claim is relatively short and sweet, much like the duct tape at the center of the controversy:

You’ll notice that Morford is suing over a piece of art called Banana & Orange, which he registered with the Copyright Office in 2020. Here’s a photo of his entire art piece that I found in a 2015 post on Morford’s Facebook page. Cattelan apparently didn’t see fit to infringe the orange, because, after all, who on earth would ever buy an orange duct-taped to a wall?

But enough about food, let’s talk about copyright infringement. Without any direct proof that Cattelan copied his work, Morford is required to plead and then establish: (1) that he owns a valid copyright in Banana & Orange; (2) that Cattelan had access to Morford’s work; and (3) that the two works are substantially similar in their protected expression.

Cattelan’s Motion to Dismiss

Cattelan’s lawyers brought a motion to dismiss the claim, at which point Morford apparently decided to read a copyright treatise from cover to cover and filed a 68-page opposition brief. (The court’s page limit was 20 pages, but no conceptual artist has ever made it big by following the rules.) Late last week, Judge Scola decided to let the fruit circus continue, denying Cattelan’s motion to dismiss (read here).

The ruling explores a number of fundamental copyright concepts that are important for anyone studying or practicing in this area to know. Unfortunately, the court got bunch of them wrong, at least when applying those concepts to the artworks at issue in the case.

Why the Court Got It Wrong

Copyrightability

The level of originality and creativity necessary to qualify for copyright protection isn’t particularly high. If you taped a synthetic banana and orange to two pieces of green poster board surrounded by masking tape, you might fail fourth grade art, but you’d be entitled to a copyright. What’s important is how far that copyright extends, but we’ll get to that later.

The court’s decision incorrectly states that Morford registered his copyright in Banana & Orange in 2000. That’s when Morford claims that he created his artwork, but he didn’t actually register the copyright until 2020, shortly before he filed his lawsuit. This is after the date of Cattelan’s alleged infringement. The delayed registration doesn’t prevent Morford from proceeding with his claim, but he won’t be able to obtain statutory damages or attorneys’ fees. This may not be a huge issue here, because Cattelan made plenty of profits which Morford can seek, but that’s not always the case, so it’s a good idea to register early. Especially before your fruit spoils.

Access

Armed with a valid copyright, Morford next needs to plead, and ultimately prove, that Cattelan had access to Banana & Orange before Cattelan created Comedian. Unfortunately for Morford, his access allegations are totally conclusory, but fortunately for Morford, the judge didn’t seem to care.

The law doesn’t require a plaintiff to have concrete evidence at the beginning of the case, but he does need to allege facts that are sufficient to state a claim that’s at least plausible. Morford provided a bit more detail in papers submitted after his complaint was filed (which is improper), but they don’t help much anyway. His access theory, stated as charitably for Morford as possible, is that Banana & Orange has been available on a publicly-accessible YouTube channel since 2008 and on a publicly-accessible Facebook page since 2015. Therefore, Cattelan had an opportunity to see the work before he created Comedian in 2019.

In addition to the 2015 Facebook post that I showed above (which was “liked” by five people), I also found a 2008 YouTube video featuring Morford’s work on a YouTube channel page for an account called “lobsterparlorart.” The channel has all of 11 subscribers, and the video featuring Banana & Orange is one of dozens of artworks displayed in the nine-minute video. You can check it out below at about one minute and eight seconds in, but the banana is displayed for less than a second, so don’t blink or you’ll miss it:

Below is a screenshot of Morford’s banana making its big reveal. At the time I watched, the video had received only 499 views in the past 14 years, three of which were from me as I was trying to find the banana:

Is it possible that Maurizio Cattelan, an artist living 10,000 miles away, was one of the few people that saw Morford’s work? Sure. But it doesn’t seem particularly plausible, and courts have routinely held that the fact that a copyrighted work is available on the internet is not, by itself, sufficient to demonstrate access. The plaintiff either needs to establish a chain of events linking his work to the defendant’s access, or else show that the plaintiff’s work has been “widely disseminated.” Morford can’t show either. Again, none of this seemed to bother the court, at least at the pleading stage, with the district judge appearing to give Morford a ton of latitude as a pro se plaintiff.

Substantial Similarity of Protected Expression

In opposing Cattelan’s motion to dismiss, Morford asserted that “[p]eople are free to duct-tape all the bananas they want to a wall; they are just not allowed to infringe my expression—claiming it as their own original artwork.” That’s all true, but Morford (and ultimately the court) both got tripped up on the boundary between protected expression and unprotected ideas.

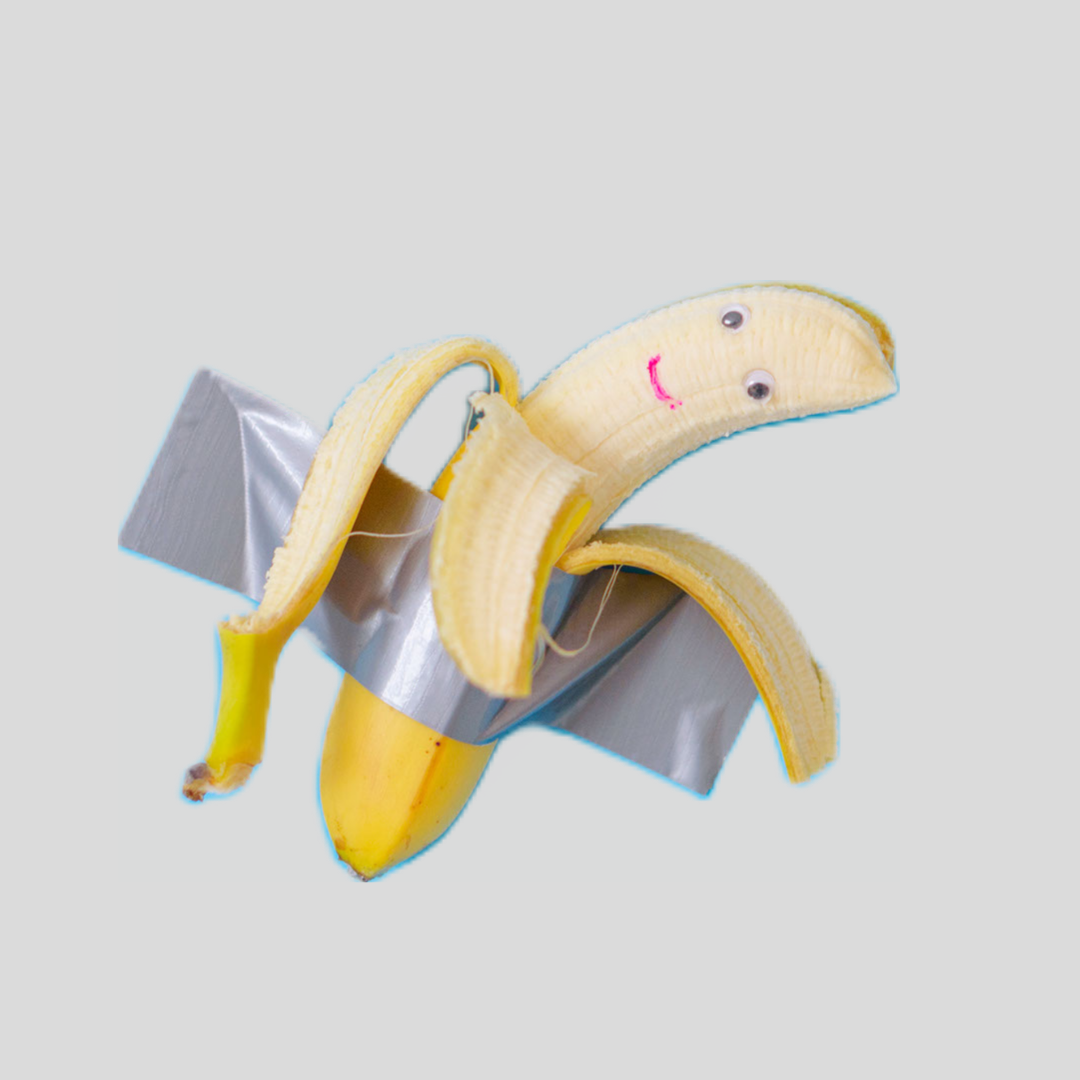

The court correctly held that “no one can claim a copyright in ideas, so Morford cannot claim a copyright in the idea of affixing a banana to a vertical plane using duct tape.” It also goes without saying that there are a lot of different ways a banana can be attached to duct tape: the banana could be rotten instead of ripe, half-eaten instead of whole, affixed with three pieces of tape instead of one, etc. Here are just a few examples:

But here’s the thing: just as a banana duct-taped to a wall is an idea, so too is the idea of an unpeeled yellow banana pointed towards the right with a single piece of duct tape across its center. It’s just described at a more specific level of abstraction. At some point you might be able to describe the abstract concept with so much concrete specificity that you’d cross over into the realm of expression. The line can be difficult to draw in some cases, but here, we aren’t even close.

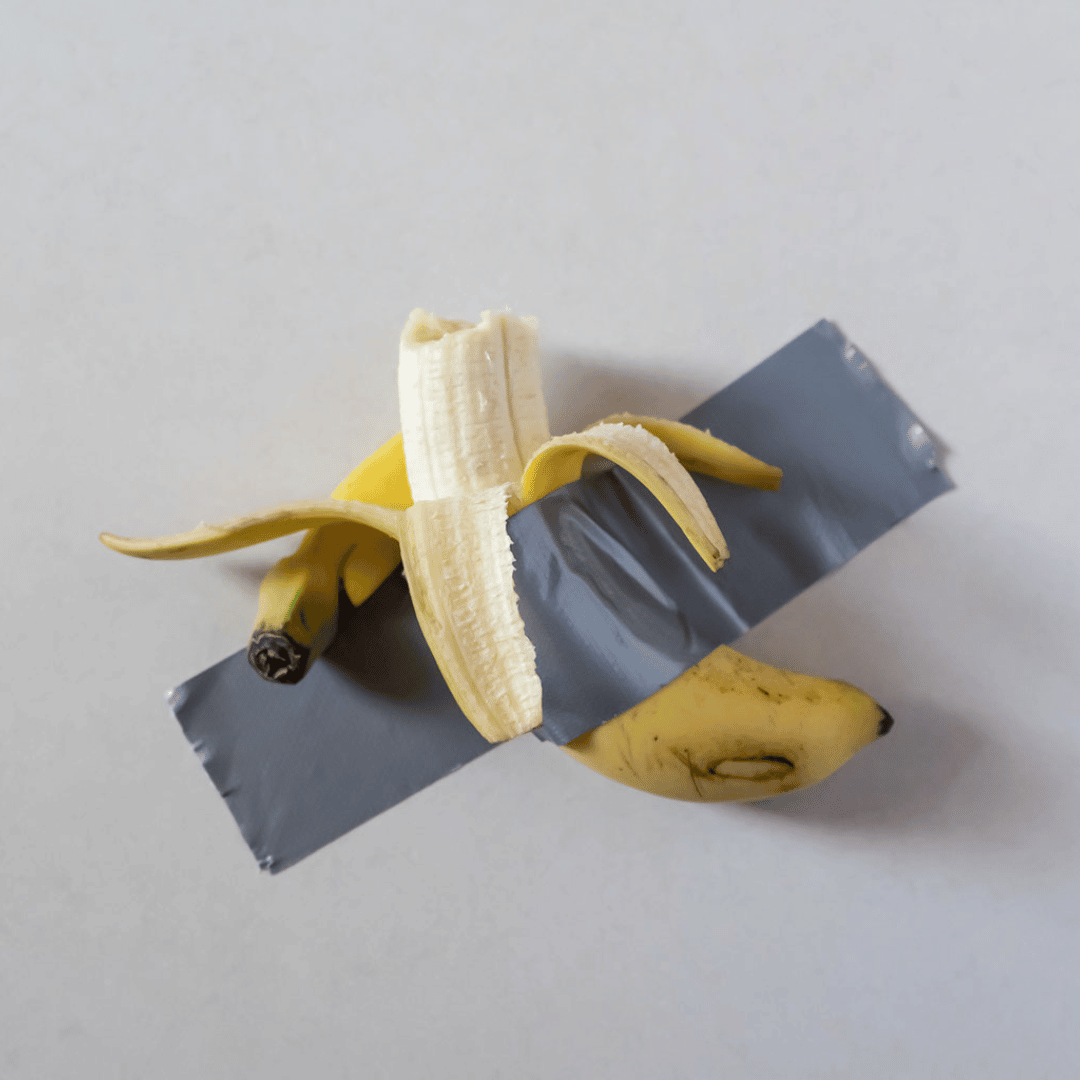

The only similarity between Morford’s art and Cattelan’s art is that one piece of silver duct tape stretches across the center of an unpeeled yellow banana that is angled downward from left to right. At that level of abstraction, allowing Morford to assert an infringement claim against a work containing entirely different aesthetic choices would essentially give him protection in an idea.

Think of it this way: if Morford could have a monopoly on his so-called “combination” of elements, there’s also no reason that he (or someone else) couldn’t also have a monopoly on art in which the banana points to the left, or in which the banana is peeled, or in which two pieces of duct tape are used to attach the banana to a wall. All it would take is a few dozen configurations that someone could prepare in 30 minutes or less to corner the entire “banana attached to wall” art enthusiast market.

This is why most courts who routinely hear these types of cases have recognized that in situations in which only a narrow range of expression is possible, copyright protection is “thin.” This is often the case for objects appearing in nature, where the range of creative choices available in selecting and arranging elements may be limited. When a resulting work contains few protectable features, it should only be protected against virtually identical copying.

Even if a court were to afford Morford’s art so-called “broad” protection, a comparison of the two works here shows that Cattelan made a number of distinct choices in his selection and arrangement of elements in Comedian when compared to Banana & Orange. These include the diptych nature of Morford’s work compared to Cattelan’s, Cattelan’s use of a white wall instead of a green background bordered by masking tape, as well as the different angles at which both the banana and duct tape are affixed.

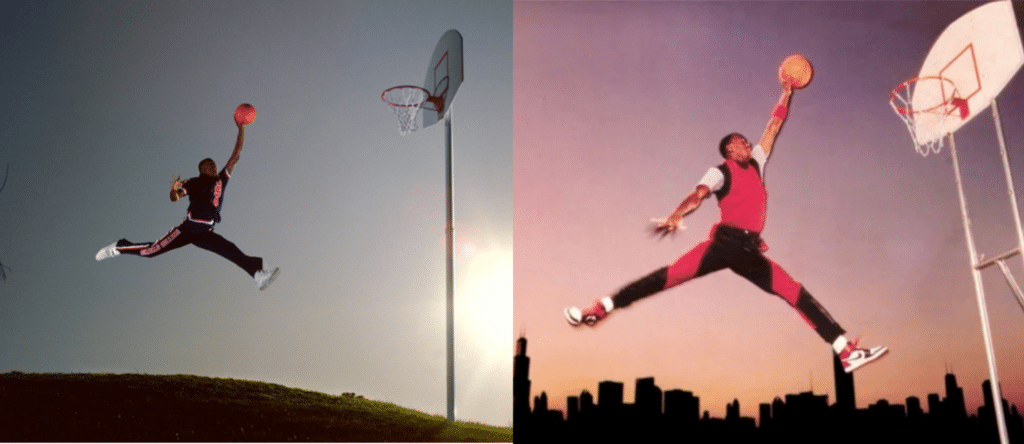

All of these elements combine to yield two works that—once their underlying ideas are excluded—aren’t “substantially similar” at all. While the two works certainly embody a similar idea, they express it in different ways, much like the two photographs of basketball superstar Michael Jordan at issue in Rentmeester v. Nike:

Both of the photos feature Jordan in his iconic “Jumpman” dunk pose, but Jordan’s pose is slightly different in each shot, as is the angle, background, and lighting. The Ninth Circuit agreed that the case was properly dismissed at the pleading stage based on these differences.

Conversely, the district judge in Morford held, at least for purposes of a motion to dismiss filed early in the litigation, that the plaintiff adequately alleged that Cattelan’s Comedian was substantially similar to the protected elements in Banana & Orange. But there was no reason that the court, having the two works before it for comparison, couldn’t and shouldn’t have decided that Morford doesn’t have a case. No amount of discovery or further motion practice could change the fact that the two works just aren’t substantially similar as a matter of law.

The Bottom Line

As I noted above, I suspect that one of the reasons the court allowed Morford’s claim to proceed was because he’s representing himself pro se. But if that’s true, the judge isn’t doing Morford any favors by stringing him along, and he certainly isn’t helping Cattelan, who is represented by highly-paid lawyers charging him by the hour. If the case is ultimately sent to a jury, all bets are off, until the inevitable a-peel. (Sorry.) At the end of the day, Morford could be ordered to reimburse Cattelan’s attorney’s fees.

Even worse, a finding that Morford has a viable claim against Cattelan would give him ammunition to proceed with similar actions against what are literally thousands of Cattelan “copycat” images that can be found on virtually every corner of the internet. Women’s Wear Daily even devoted an article to the internet memes that began to pop up after Cattelan’s sale of Comedian. None of these people were looking to copy Joe Morford, yet here we are. And as long as we’re here, we might as well add this one to the pile, courtesy of yours truly:

So, do you agree that Morford’s case was kept past its shelf life, or do you think it’s still ripe? As always, let me know in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the Court’s order that isn’t covered with a piece of tape or a piece of fruit:

View Fullscreen