Can you copyright a rhythm? The world’s biggest pop star says no, and the future of the entire reggaetón industry may hang in the balance.

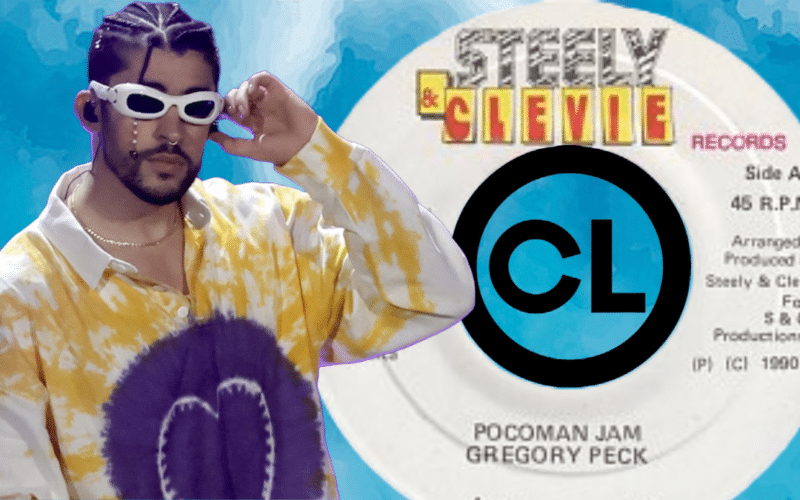

Bad Bunny is hoping he’s hare today, gone tomorrow from a massive copyright infringement lawsuit that reads more like a list of nominees for the Latin Grammy Awards than a legal caption.

Late today, the Puerto Rican rapper filed a motion (read here) asking to be dismissed from a consolidated complaint brought against more than 150 popular reggaetón artists, songwriters, and record companies by representatives of famed Jamaican dancehall producers Steely & Clevie. If misery loves company, Bad Bunny is certainly in good company, with genre superstars Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee, Karol G, Maluma, Pitbull, and Ozuna also part of the case. (Lest you think that it’s a totally exclusive club, Justin Bieber is even named as a defendant for his featured role on the “Despacito” Remix.)

UPDATE—May 30, 2024—Judge André Birotte Jr. largely denied the defendants’ bid for an early dismissal of this massive reggaetón lawsuit, finding that it would be “premature at this stage to find that the musical elements alleged are insufficiently original or indeed unprotectable.” So, for now at least, the case proceeds. Read the court’s order here.

The Dem Bow Rhythm

The lawsuit targets pretty much the entire reggaetón industry, claiming that nearly 1,700 songs infringe the copyright in a rhythm that has arguably become the backbone of reggaetón:

That rhythm (or, more aptly, “riddim” in the dancehall and reggae vernacular) is best known as “Dem Bow,” after the Shabba Ranks song of the same name. Dem Bow is itself based on a drum beat the plaintiffs claim was first recorded in 1990 in the Steely & Clevie-produced “Fish Market.” The Fish Market/Dem Bow riddim (also known as “Poco Man Jam” from an early track to incorporate it) was subsequently used by reggae producers as an ingredient to create many other riddims, the most well-known of which is the Pounder riddim, which adds some timbale drums beats not found in “Fish Market.”

As the music migrated from Jamaica to Panama to Puerto Rico, the Pounder riddim has been sampled, chopped up, remixed, or interpolated into countless reggaetón songs. One scholar estimated that up to 80% of all reggaetón music can be traced to this one drum beat, which—at least indirectly—can be traced to Steely & Clevie.

Steely & Clevie vs. Reggaetón

According to the plaintiffs, Bad Bunny is responsible for over 40 songs that use drum and bass patterns from Steely & Clevie’s “Fish Market,” including “MIA,” his collaboration with Drake; “La Santa” with Daddy Yankee; and “Safaera” with Jowell & Randy.

patterns throughout most of the work.”

In addition to Bad Bunny, most of the other defendants named in the lawsuit also filed motions to dismiss today. Those motions largely target claimed technical deficiencies in Steely & Clevie’s complaint—the plaintiffs’ lack of standing, a lack of clarity regarding the particular elements of “Fish Market” allegedly infringed, and various procedural defects. By contrast, Bad Bunny is taking Steely & Clevie’s allegations at face value for purposes of his motion to dismiss, but argues that they don’t matter because, he says, the original Dem Bow riddim is a “basic building block of music” that isn’t protectable under U.S. copyright law.

Bad Bunny is also looking to use Steely & Clevie’s claims to have created a “genre-defining” beat against the plaintiffs, arguing that the very fact that they’ve sued so many artists over so many songs is a tacit admission that the Dem Bow rhythm is unprotectable scènes à faire—in other words, “commonplace elements that are firmly rooted in the genre’s tradition.”

Can You Copyright A Rhythm?

This brings us to the billion-dollar issue: Is rhythm copyrightable? It’s actually a somewhat esoteric question. At what point does the sky stop being partly cloudy and start becoming partly sunny? Who gets the middle armrest on a plane? Can sheep live underwater? (Yes, for about 30 seconds.) “Rhythm” in and of itself is just a pattern of notes or beats, and these sounds can be arranged, emphasized, and spaced out in different ways. Some of these patterns can be complex, but most are incredibly simple, and courts have rightfully held that common rhythmic patterns aren’t protectable any more than short phrases in a literary work. However, if enough short phrases are linked together—or rhythmic elements are combined with other musical elements like melody, harmony, and arrangement—they may become sufficiently numerous enough or original enough to qualify for copyright protection.

Just last month, Southern District of New York Judge Louis Stanton threw out Structured Asset Sales’ copyright lawsuit against Ed Sheeran after a jury cleared Sheeran of similar allegations over his hit “Thinking Out Loud.” The judge found that the chord progression and harmonic rhythm in the allegedly-infringed “Let’s Get It On” are so commonplace, both in isolation and in combination, that “to protect their combination would give ‘Let’s Get It On’ an impermissible monopoly over a basic musical building block.”

Other courts have also held that common musical elements like song structure patterns and basic harmonic progressions are either too unoriginal to be copyrighted or are so commonplace that they’re unprotectable scènes à faire. In one particularly fulsome analysis of copyright and rhythm, a Louisiana district court in Batiste v. Najm concluded that “the basic harmonic and rhythmic building blocks of music, especially popular music, have long been treated by courts as well-worn, unoriginal elements that are not entitled to copyright protection.”

To be sure, a combination of more unique and numerous elements will at some point “cross over” into the realm of protectability, but the basic building blocks of music need to be freely available for everyone to use. Otherwise, the first person who came up with, for example, the now common four-on-the-floor pattern could corner the market. Or consider the famous Bo Diddly beat. This rhythmic pattern was influenced by traditional sub-Saharan African music and then itself served as the influence for countless rock and pop songs, from The Who’s “Magic Bus,” to U2’s “Desire,” to George Michael’s “Faith,” and hundreds more.

Reggaetón beats are actually pretty simple. And that’s perfectly fine—it’s probably part of why the genre is appealing. The four-to-the-floor kick pattern with an offbeat snare and some added percussion provides a canvas for the vocal-rap-instrumental combo that makes Latin music so popular. This video gives a good two-minute explanation of what I’m talking about:

Yep. That’s about all there is to it. While Central District of California Judge André Birotte Jr. may be hesitant to throw out Steely & Clevie’s complaint at the pleading stage, I think the plaintiffs are ultimately going to have a tough time with their case and that the so-called “Dem Bow Tax” won’t come to pass.

As always, I’d love to know your thoughts. You can leave comments below or at @copyrightlately on social media. Meanwhile, here’s a copy of Bad Bunny’s motion to dismiss, which is currently set for a September 22, 2023 court hearing.