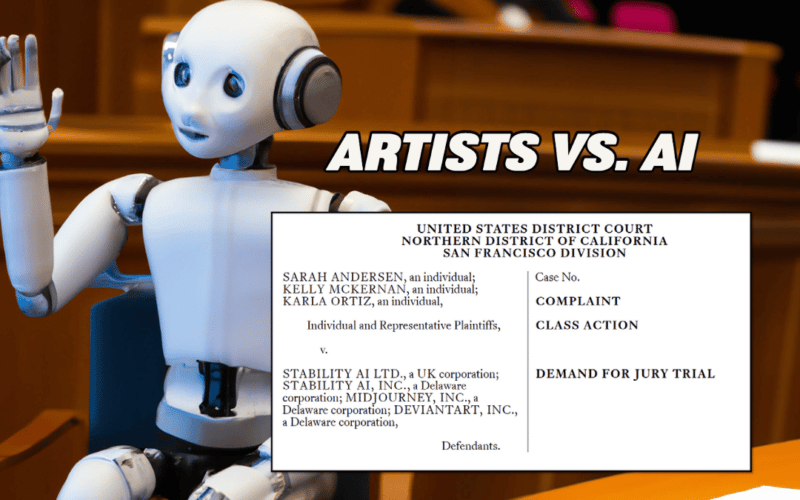

A group of artists has filed a first-of-its-kind copyright infringement lawsuit against the developers of popular AI art tools, but did they paint themselves into a corner?

Depending upon who you ask, AI-generated art is either poised to thrust a photorealistic dagger into the throats of millions of commercial artists or is merely a kitschy fad with no lasting aesthetic value. While the truth almost certainly lies somewhere in between, there’s no denying the legitimate concerns expressed by many artists about the manner in which current AI tools were trained and their potential to disrupt creative livelihoods.

Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd.

On January 13, three of those artists, Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan and Karla Ortiz—along with a proposed class of potentially millions more—brought the first copyright infringement lawsuit of its kind (complaint here) against the developers of several popular AI art generation tools. The defendants include Stability AI (developer of Stable Diffusion and DreamStudio), Midjourney (which packaged the open-source Stable Diffusion into its own Discord and web-based applications) and DeviantArt (which recently launched the DreamUp app, also based on Stable Diffusion’s platform). Open AI, which created the popular Dall-E 2 program, wasn’t named in the lawsuit, likely because the content of its training data hasn’t been made public.

Over the past week, the plaintiffs’ lawsuit has been the subject of thousands of articles which have largely parroted the complaint’s key talking point: that AI image generators are nothing more than “a 21st-century collage tool that remixes the copyright works of millions of artists whose work was used as training data.”

After the initial headlines have run their course, plaintiffs’ legal team will be left with the decidedly more difficult task of actually proving their case. Unfortunately, I think members of the artistic community (and putative class members) will be disheartened to learn that many of the facts and legal theories underlying plaintiffs’ allegations don’t square with the soundbites, and may even hurt artists more than they help.

The Complaint Doesn’t Accurately Describe How Defendants’ AI Tools Work

Diffusion Models Don’t Create Collages

As a factual matter, the complaint misrepresents how AI diffusion models like Stable Diffusion actually work. These tools aren’t like some sort of DJ Earworm megamix sampling bits and pieces from an image database and mashing them together. As I noted in an earlier post, the programs use data from training images and their associated text to identify the essential qualities of objects and to discover relationships between their fundamental elements. Once trained, the tools can create, not “seemingly new images,” as plaintiffs assert, but entirely new works from the ground up.

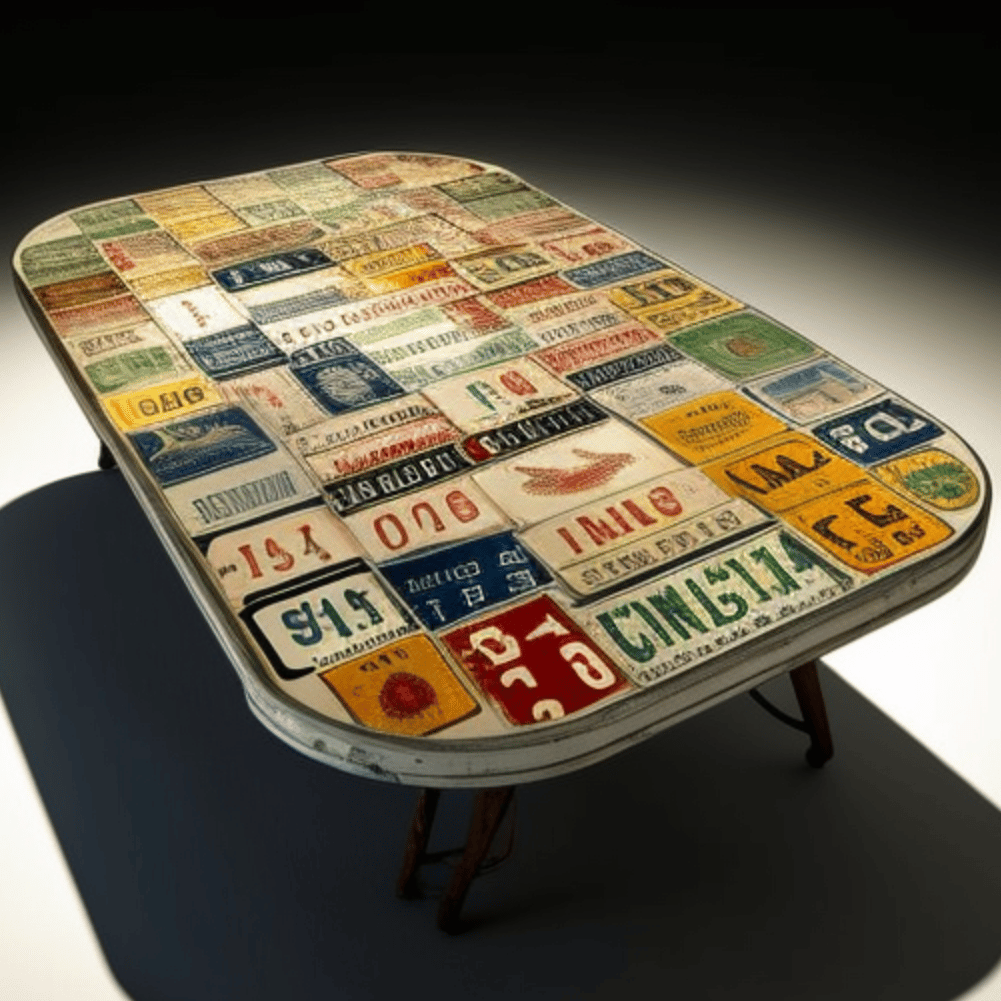

To use a simple example, let’s say the AI program analyzes data from millions of text-image pairs containing the word “tables.” The tool will learn that a table is a piece of furniture with one or more legs and a flat top. It will learn that tables most commonly have four legs, but not always; that tables found in a dining room are used for seated persons to eat meals, while tables found next to a bed are used to hold objects like alarm clocks; that tables don’t need to be made from any particular material or have a particular color, etc.

The tool can then apply its knowledge of tables to the knowledge it has acquired about aesthetic choices, styles and perspectives, all en route to creating a new image that’s never existed before. There’s no “cutting and pasting” involved. (If you’re interested in doing a deeper dive into how all of this works, I recommend following Andres Guadamuz’s blog on the topic.)

With a proper understanding of the technology, we can see that the complaint’s repeated description of Stable Diffusion as a “21st-Century collage tool,” while perhaps catchy, simply isn’t accurate.

Stable Diffusion Doesn’t Store Copies of Training Images

The complaint also mischaracterizes Stable Diffusion by asserting that images used to train the model are “stored at and incorporated” into the tool as “compressed copies.” The current Stable Diffusion model uses about 5 gigabytes of data. None of it includes copies of images. It would be physically impossible to copy the 5 billion images used to train the dataset into a 5GB file in a way that would allow the tool to spit out representations of those images, no matter how small you tried to compress them.

The complaint gives the example of a text prompt for the phrase “a dog wearing a baseball cap while eating ice cream,” and claims that the system “struggles” with generating an image based on this prompt because although there are many photos of dogs, baseball caps and ice cream among the training images, there are “unlikely to be images that combine all three.” A latent diffusion system can’t illustrate this combination of objects, plaintiffs assert, “because it can never exceed the limitations of its Training Images.”

This might be true if Stable Diffusion actually had to locate a particular image in the way a search engine does, but because that’s not how the tool works, it took me about fifteen seconds to type this prompt into Midjourney and get a serviceable result:

Reproduction Rights vs. Derivative Rights

With a better understanding of how the technology in fact works, we can turn to the complaint’s legal theories.

Inputs

When it comes to potentially infringing actions committed by the developers of AI tools, the most likely candidate is the initial scraping (i.e., reproduction) of images in order to train the model. Whether this conduct constitutes actionable infringement or is instead a protected fair use will hinge in large part on the court’s assessment of whether the images were copied and used for a transformative purpose (akin to Google’s Book Search tool or the Turnitin plagiarism detection software), weighed against the commercial nature of these tools and their ability to negatively impact the licensing market for the underlying works.

As I noted in my prior article on AI art, AI tools aren’t copying images so much to access their creative expression as to identify patterns in the images and captions. In addition, the original images scanned into those databases, unlike Google’s display of book snippets, are never shown to end users. This arguably makes the use of copyrighted works by Stable Diffusion even more transformative than Google Book Search.

Surprisingly, plaintiffs’ complaint doesn’t focus much on whether making intermediate stage copies during the training process violates their exclusive reproduction rights under the Copyright Act. Given that the training images aren’t stored in the software itself, the initial scraping is really the only reproduction that’s taken place.

Outputs

Nor does the complaint allege that any output images are infringing reproductions of any of the plaintiffs’ works. Indeed, plaintiffs concede that none of the images provided in response to a particular text prompt “is likely to be a close match for any specific image in the training data.”

Instead, the lawsuit is premised upon a much more sweeping and bold assertion—namely that every image that’s output by these AI tools is necessarily an unlawful and infringing “derivative work” based on the billions of copyrighted images used to train the models.

This allegation is factually flawed and legally suspect; it’s also overreaching in a way that could actually undermine the work of many artists who are members of the proposed class. But before we get there, we need to ask a fundamental question: What’s a derivative work?

Let’s Talk About Derivative Works

Subject to fair use and other defenses, a copyright owner has the exclusive right to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.

You might assume that the concept of a “derivative work” under copyright law would be simple to define. You’d be wrong. Sure, there’s a definition included in the 1976 Copyright Act itself, but barrels of ink have been spilled by copyright lawyers, scholars and judges trying to make sense of what it actually means.

The Copyright Act Definition is Broad, But . . .

Let’s start with the Copyright Act’s definition:

A “derivative work” is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.

17 U.S.C. § 101

Notice that a derivative work is defined as one that’s “based upon” one or more preexisting works. This is likely the concept that plaintiffs’ complaint is latching onto when it asserts that the output produced by AI art tools is “necessarily” derivative of the dataset of preexisting copyrighted works.

Derivative Works Must Incorporate a Portion of the Underlying Work

While the definition of “derivative work” is admittedly broad, it doesn’t mean that any new work that’s loosely “derived” from another work qualifies as a derivative work—let alone an infringing work. As I noted in a few Twitter and Mastodon threads last week (follow me here and here), whether or not a particular image generated by an AI art tool is a “derivative work” is ultimately irrelevant to the question of infringement.

The legislative history of the 1976 Copyright Act explains that to violate an artist’s derivative works right, a new work must incorporate a portion of the underlying work. It gives the example of a musical composition inspired by a novel, which would not normally constitute infringement. In the Ninth Circuit—the jurisdiction in which the class action lawsuit against Stability AI and the other defendants has been filed—the court in Litchfield v. Spielberg held that a work is not an infringing derivative work unless it’s “substantially similar” to a preexisting work. Only then has the former “incorporated” the latter.

Interestingly, while plaintiffs allege that each image output by Stable Diffusion is “necessarily a derivative work” of all the training images, they concede that “none of the Stable Diffusion output images provided in response to a particular Text Prompt is likely to be a close match for any specific image in the training data.” This acknowledgement seems to throw a giant wrench into plaintiffs’ derivative work claim which, as I noted earlier, is really the crux of their lawsuit.

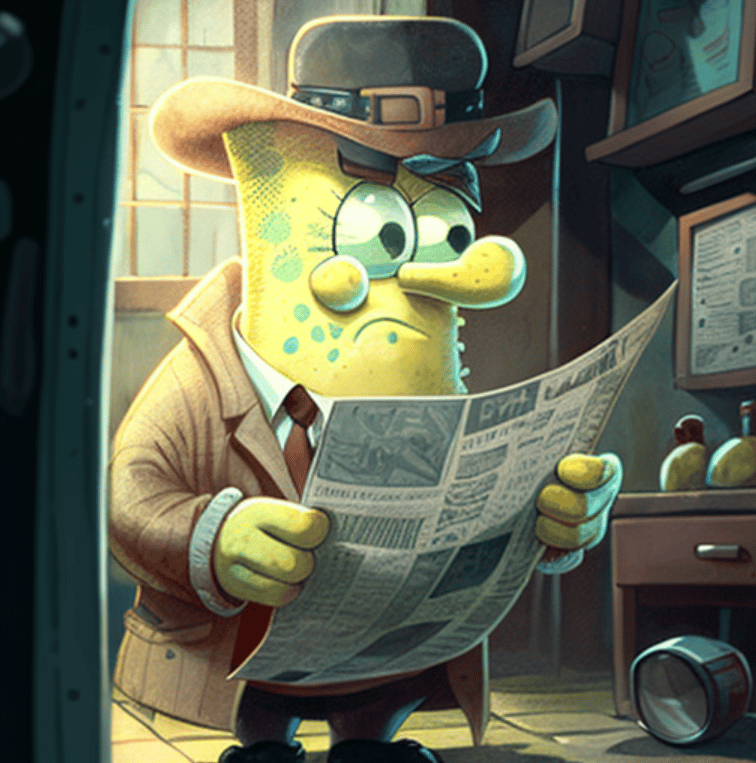

Stable Diffusion can certainly be coaxed into generating a work that’s derivative of elements found in another work—some of which may be separately copyrightable. In particular, images of popular characters like Mickey Mouse, Homer Simpson and SpongeBob SquarePants that are all over the internet can be easily generated in unique settings. In essence, the tool can learn the essential elements of SpongeBob in the same way it learns the essential attributes of a table.

This also explains why fragments of artists’ signatures or pieces of Getty Images’ watermark may show up in output images. There are ways to temper the effect of “overtraining” models on ubiquitous images, but it’s important to remember that even if a generated output image is original, it may still be infringing if it substantially incorporates protectable elements from another work.

It should be clear by now that determining whether particular output images are infringing requires an image-by-image comparison, and a class action lawsuit really isn’t the best vehicle for that sort of thing.

The Danger in Overreaching

There’s another, more fundamental problem with plaintiffs’ argument. If every output image generated by AI tools is necessarily an infringing derivative work merely because it reflects what the tool has learned from examining existing artworks, what might that say about works generated by the plaintiffs themselves? Works of innumerable potential class members could reflect, in the same attenuated manner, preexisting artworks that the artists studied as they learned their skill.

If adopted by the court, plaintiffs’ broad assertion would have dire implications for the very artists the lawsuit is trying to protect. Any time artists produce creative works, they draw upon what they’ve seen and experienced throughout their lives. In this sense, all human creative work is derivative. Many artists specifically work to build upon or remix styles, techniques and even expressions first created by other artists.

A Matter of Style

For this reason, the complaint’s related suggestion that a tool capable of creating art in the “style” of another artist is unlawful is also dangerous. Style is certainly an element that can and should be considered within an overall substantial similarity analysis, but prohibiting works that are merely “inspired by”—or even copy—preexisting art techniques would artificially stifle human creative development.

The courts that have considered this issue have held that style is an ingredient of expression, but that standing alone, it isn’t protectable. So even if one artist were the first to think up the style of anime, for example, “he could only have a protectible copyright interest in his specific expression of that idea; he could not lay claim to all anime that ever was or will be produced.”

In another example, a court found that the defendants’ movie poster unlawfully copied the plaintiffs’ New Yorker cartoon. That’s because the two works not only used the same “sketchy, whimsical” style, but did so using the same subject matter, the same theme and even identical concrete details in a substantially similar way. That’s improper. On the other hand, one artist is perfectly free to use the same subject and style as another artist “so long as the second artist does not substantially copy [the first artist’s] specific expression of his idea.”

The Right of Publicity Claim

Note that plaintiffs have also asserted a separate right of publicity claim under California law based on Stable Diffusion’s ability to generate outputs in a particular artist’s “style” when the artist’s name is invoked in a prompt. The reason the tools can recognize certain artists’ names and styles is the same reason they recognize objects of furniture—this is factual information that’s often included in the captions or alt text associated with training images.

It’s an interesting theory, but I don’t think it ultimately works unless there’s some evidence that the defendants used the plaintiffs’ names in a manner that’s directly connected to the promotion of the tools or in some other overtly commercial way. If it’s really just a backdoor attempt to control the artistic works used in the training sets, the claim is likely preempted by the Copyright Act.

Vicarious Liability

It’s also important to remember that any potentially infringing derivative images output by Stable Diffusion are created in response to prompts input by the individuals using the programs, not by the defendants themselves. While the plaintiffs have asserted a claim for vicarious infringement based on users’ conduct, it doesn’t strike me as particularly strong.

To be vicariously liable for another person’s copyright infringement, a defendant must have the right and ability to supervise the direct infringer. Stability AI and the other defendants can’t control the prompts that are input by users.

Public-facing tools like Midjourney should be eligible to invoke the DMCA’s “safe harbor” provisions with respect to user-generated content in public Discord servers. (Midjourney has set up a notice and takedown system for this purpose.) But software installations of Stable Diffusion on users’ local machines are a lot like the peer-to-peer software at issue in MGM v. Grokster (which rejected a vicarious liability claim). In that case, the Supreme Court held that “none of the communication between defendants and users provides a point of access for filtering or searching for infringing files, since infringing material and index information do not pass through defendants’ computers.”

Also, as I explained a while back in an article about YouTube stream-ripping software, just because a particular tool may be used for an infringing purpose doesn’t automatically mean that the manufacturer faces secondary liability for distributing the tool. The manufacturer would need to take additional action that contributed to or induced infringement by users. Notably, in 1984’s “Betamax” opinion, Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, the U.S. Supreme Court expressly held that so long as a technology is capable of “substantial noninfringing uses,” the manufacturer couldn’t be held liable “simply because the equipment is used by some individuals to make unauthorized reproductions of [plaintiffs’] works.”

If vicarious liability is to be imposed on Sony in this case, it must rest on the fact that it has sold equipment with constructive knowledge of the fact that its customers may use that equipment to make unauthorized copies of copyrighted material. There is no precedent in the law of copyright for the imposition of vicarious liability on such a theory.

Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 419 (1984).

The Limits of Law

The true concern driving plaintiffs’ lawsuit is summarized in the complaint’s introduction, which asserts that “Plaintiffs and the Class seek to end this blatant and enormous infringement of their rights before their professions are eliminated by a computer program powered entirely by their hard work.”

This concern is understandable, but it’s not one that plaintiffs’ lawsuit is equipped to solve. The plaintiffs’ lawyers have stated that “Even assuming nominal damages of $1 per image, the value of this misappropriation would be roughly $5 billion.” Sure, that’s a big number in the aggregate, but it would collectively net the three named plaintiffs less than $250 based on the 242 works they claim were used as training images. (Note that McKernan and Ortiz don’t appear to own any registered copyrights, which is required for them to be proper plaintiffs in the first place.) More importantly, no damages award would put the AI-generated genie back in the bottle.

I also have to believe that an “ethically sourced” AI tool, trained only with images obtained via an opt-in or licensing model, could be programmed to produce output that would rival that of the models at issue in the lawsuit. Such a tool might avoid the legal or ethical baggage of Stable Diffusion, but would do nothing to stop the proliferation of AI-generated art.

While the law isn’t likely to provide much comfort to the plaintiffs, history may. Consider that way back in 1859, French art critic Charles Baudelaire grumbled that if a then-new technological development were “allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally.”

Baudelaire was talking about photography, but he may as well have been venting about AI-generated art. The truth is that many new creative innovations—from the advent of Photoshop, to the widespread adoption of digital photography, to the introduction of 3D computer-generated animation—have been met with resistance. Ultimately, each of these technologies was embraced as a tool, not of displacement or corruption, but supplementation, allowing artists to unlock entirely new forms and styles of creative expression.

I’ll be keeping a close eye on legal developments in Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd. and will post updates here on Copyright Lately. In the meantime, I’d love to know what you think about the new lawsuit. Drop me a comment below or @copyrightlately on social media.

8 comments

I wonder if these lawsuits will bring up the question of ownership of a prompt or image. Should AI generated images be automatically public domain or unable to be protected by copyright.

You might like to read up on https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ai-art-intellectual-property-lawsuit-stephen-thaler-2242031

At least in the U.S., whether something is copyrightable depends on the “traditional human authorship” of the work. It’s probably going to have to be set by precedent, but I think it goes one of two ways: the human who operated the system demonstrates that their input was what lead to the specific output, or any product of A.I. regardless of how much human input was involved is ineligible.

Personally, I think it’d be very entertaining if major entertainment studios include A.I. generated content in big budget works and then sue people for copyright infringement for pirating their movie or game – will the part(s) produced using A.I. generation be ineligible for protection? Will textures, models, music or even software be “ok to pirate” since it was A.I. generated?

How do you determine an AI-generated image? And what happens when someone edits that image? How much editing is required before you’re allowed to take ownership of an image?

I would imagine a law like that would be completely unworkable and unenforceable.

Very pertinent question.

It would seem that the lawyers are abusing the not-tech-savvy who are, in turn, hoping the judges aren’t tech savvy. The fact that there are people named as plaintiffs who don’t even have registered copyrights makes this entire thing even more ludicrous. If, by some miracle, it gets upheld by the court, it surely won’t be on appeal.

I don’t disagree that there may be a case to be argued about copyright (not that I think it should win), but they need to at least do their research and come up with a valid complaint before making it.

Tech is advancing. The law needs to catch up. This case won’t do anything to make it do that. These are just scared artists grabbing are straws they don’t understand.

This is such a great take and read on the topic.

Compelling counter. And yet, it feels like there is still something “not quite right” with AI models relying on human art to produce artificial art without any form of compensation for human artists whose work is used for training purposes.

Pathetic defense of AI from Moss and Matt. Are you still humans or just machines fueled by money?