The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) is asking the Second Circuit to reconsider its recent fair use ruling over Warhol’s “Prince Series,” arguing that the decision “threatens to render unlawful many of the most historically significant artistic works of the last half-century.”

UPDATE—August 24, 2021—The Second Circuit granted AWF’s petition for rehearing, only to reaffirm its original finding of no fair use. The panel “emphatically reject[ed]” AWF’s argument that the Supreme Court’s subsequent Google v. Oracle case changes the result in Goldsmith. The court noted that Google was a case about “copyrights in computer code” which “may well make its conclusions less applicable to contexts such as ours.” At the same time, the court stated that “both opinions recognize that determinations of fair use are highly contextual and fact specific, and are not easily reduced to rigid rules.” Check out the Second Circuit’s amended ruling here.

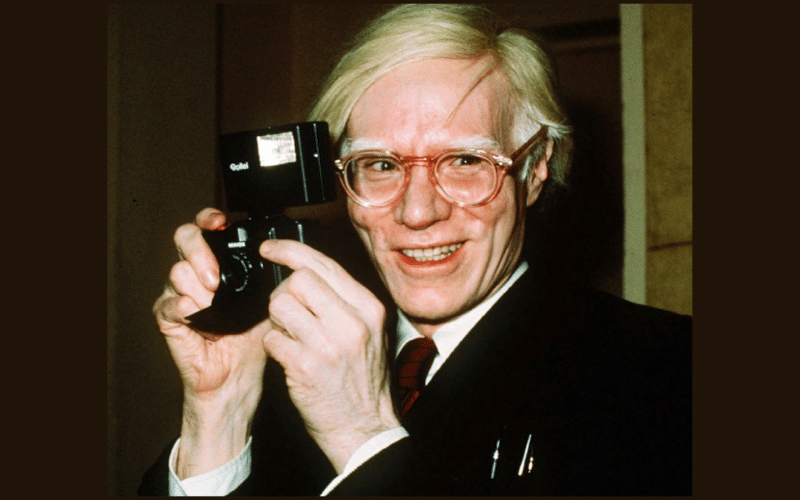

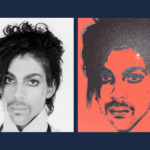

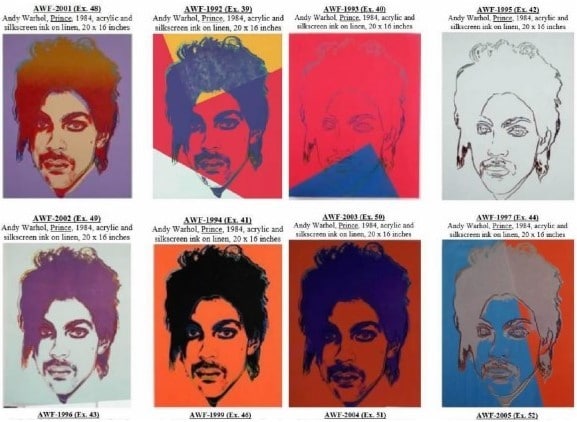

As I discussed last month here on Copyright Lately, in March the Second Circuit held that Andy Warhol’s use of photos of the pop icon Prince wasn’t “transformative” and therefore didn’t qualify as fair use under the Copyright Act. Among other things, the court suggested the fact that a new work “recognizably deriv[es]” from and retains the “essential elements” of its source material—as the Prince Series clearly did—cuts against a fair use finding.

Just over a week after the Second Circuit’s ruling in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its long-awaited decision in Google v. Oracle, which gave a fair use green light to Google’s verbatim copying of certain Java API’s.

In its new petition filed today, AWF argues that the Second Circuit’s Warhol decision conflicts with Google and other established precedent by establishing a “first-of-its-kind categorical rule” on transformative use that effectively forecloses the fair use defense from any creative work that that “recognizably derive[s] from, and retain[s] the essential elements of,” a pre-existing one—”even where the new work has a different meaning or message from the original.”

AWH asserts that such a rigid definition of transformation can’t be squared with the facts or holding of Google, in which the defendant “copied” the plaintiff’s software code “precisely,” and did so for “the same reason” that the plaintiff wrote it. Even though such line-for-line copying was obviously “recognizable” in the new work, it was nevertheless transformative.

In addition to arguing that the Warhol decision conflicts with Google, AWH contends that the Second Circuit’s decision creates an “open conflict” with other circuit courts—most notably the Ninth Circuit. Citing Green Day v. Seltzer, AWH asserts that the Ninth Circuit took a more permissive view of transformative use in cases where a work provides a “plainly distinct” message on a subject, even where the original drawing that was copied was prominent and readily recognizable in the new work.

To the extent works like the Prince Series do not make fair use of their source material, AWF argues, “[c]ountless seminal works of contemporary art would be imperiled to suffer the same fate.” Museums couldn’t lawfully display the works, owners couldn’t lawful resell them, and “artists like Warhol lose all copyright protection.”

As I noted in my discussion of the Goldsmith opinion, there’s no doubt that the case injects added confusion into the fair use inquiry, especially because it’s difficult to square with the Second Circuit’s prior decision in Cariou v. Prince. That said, panel rehearing and en banc review is exceeding rare in the Second Circuit, and based on the statistics alone, AWF’s attempt to undo the court’s decision faces an uphill battle.

A copy of AWF’s petition for panel rehearing and rehearing en banc is below.

View Fullscreen