The ink’s not even dry on Warner Chappell Music v. Nealy, yet the Court is already poised to make its new decision on copyright damages obsolete.

Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its much-anticipated opinion in Warner Chappell Music, Inc. v. Nealy, ruling that, so long as a claim is timely filed, a copyright plaintiff is “entitled to damages, no matter when the infringement occurred.”

Creative Cheers and Legal Uncertainties

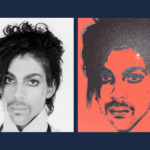

The Court’s decision was immediately celebrated by artists, photographers, and other members of the creative community. That’s because it does away with a nationwide split among appellate courts, including a 2020 ruling by the influential Second Circuit Court of Appeals that limited copyright infringement damages to three years before the filing of a lawsuit, even if the plaintiff had been unaware of earlier infringements.

For the plaintiff, music producer Sherman Nealy, the Court’s ruling means the right to pursue damages dating back to 2008, ten years before he filed suit. Nealy was in prison when his musical works were allegedly infringed—a pretty decent excuse as far as excuses go—and says he didn’t discover the infringements earlier.

Writing for the majority, Justice Kagan assumed, without deciding, that the so-called “discovery rule” applies, under which copyright claims accrue when “the plaintiff discovers, or with due diligence should have discovered” an infringing act. It’s a premise that was shared by both parties in the case as well as every circuit court of appeals that has addressed the issue.

But it’s a potentially precarious assumption.

The Copyright Act’s statute of limitations provision is deceptively simple: “No civil action shall be maintained under the provisions of this title unless it is commenced within three years after the claim accrued.” Generally, a cause of action accrues and the statute begins to run when a defendant commits an act that injures a plaintiff. While the Supreme Court has recognized that a statute of limitations may be equitably tolled in cases of fraud, concealment, latent disease and medical malpractice—again, pretty good excuses as far as excuses go—the Court has typically refused to apply a general discovery accrual rule when a statute is silent on the issue.

The Nealy Dissent

Dissenting from the Court’s Nealy opinion, Justices Gorsuch, Thomas and Alito criticized the majority for sidestepping the elephant in the room, and left no question as to how they would have decided the issue had it been squarely presented:

“Rather than address that question, the Court takes care to emphasize that its resolution must await a future case. The trouble is, the Act almost certainly does not tolerate a discovery rule. And that fact promises soon enough to make anything we might say today about the rule’s operational details a dead letter.”

Justice Gorsuch, dissenting from the Supreme Court’s opinion in Warner Chappell Music v. Nealy

The three dissenters may not be alone. In a 2001 opinion involving the Fair Credit Reporting Act, former Justice Ginsburg cautioned that while lower federal courts generally apply a discovery rule when a statute is silent on the issue, “we have not adopted that position as our own.” In 2014’s Petrella decision, a majority led once again by Justice Ginsburg observed, without passing on the issue, that the limitations period typically begins to run at the point when the plaintiff can file suit and obtain relief: “A copyright claim thus arises or accrues ‘when an infringing act occurs.'”

And in 2019, eight members of the Court—including Justices Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan and Kavanaugh—held that there is no blanket discovery rule that applies to all cases arising under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. More broadly, Justice Thomas, writing for the majority, echoed an earlier quip by former Justice Scalia that an expansive approach to the discovery rule is a “bad wine of recent vintage.”

In his dissent in Nealy, Justice Gorsuch remarked that, rather than “expound on the details of a rule of law that [the parties] may assume but very likely does not exist,” he would have waited for another case squarely presenting the question whether the Copyright Act authorizes the discovery rule.

Hearst v. Martinelli: What’s Next

It may not be a long wait. The Court is currently scheduled to review a petition filed by Hearst Newspapers that does precisely that, asking the Court to decide “[w]hether the ‘discovery rule’ applies to the Copyright Act’s statute of limitations for civil claims.”

The ongoing debate over the discovery rule highlights the tension between ensuring fairness to plaintiffs who might be unaware that their rights have been infringed and providing certainty to defendants who could be subject to long-dormant claims. The Supreme Court’s reluctance to broadly apply the discovery rule underscores a preference for a more predictable legal framework, although this can sometimes lead to harsh outcomes for plaintiffs who discover infringements too late.

If that’s the approach the Court chooses to take with Hearst, the creative community’s celebration over Nealy may be as fleeting as the decision itself.

As always, I’d love to hear what you think. Drop me a note below or @copyrightlately on social media.

View Fullscreen

1 comment

There is such a strong “if Congress wanted that it would have put it in the Copyright Act” strand that has run through so many justices. I think you have at least five who will say no such discovery rule.