Answer songs face the music: the ‘Flowers’ lawsuit threatens a long tradition of musical conversation and creative expression.

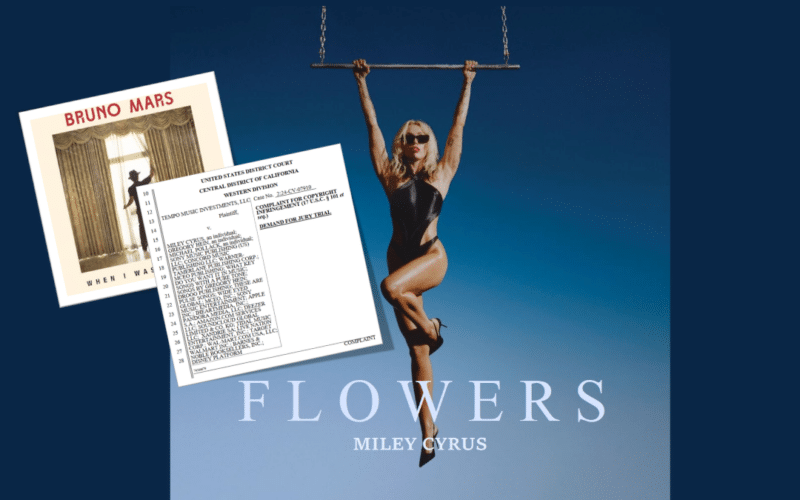

For as long as music has existed, musicians have been writing songs reacting to other artists’ songs. The fancy “I was an English lit major at Yale” word for this is intertextuality. If that sounds vaguely risqué—like two texts hooking up for a passionate night of cross-referencing—you’re not far off. Call it a response song, an answer song, a diss track, clapback, or homage. But don’t call it copyright infringement—at least not in the case of Miley Cyrus’s 2023 smash hit “Flowers,” which is a thinly-veiled rejoinder to the 2013 Bruno Mars song “When I Was Your Man.”

That hasn’t stopped Tempo Music Investments from planting a lawsuit anyway. Earlier this week, Tempo filed a much-publicized complaint (read here) against Cyrus and nearly 30 others, including co-writers, record companies, streaming platforms, and retailers, claiming that “Flowers” copies substantial portions of “When I Was Your Man.” The lawsuit points to alleged similarities in the lyrics, pitch design, and chord progressions between the two songs. While Mars isn’t named as a plaintiff, Tempo Music—a private equity-backed fund that in 2020 bought a portion of the rights to “When I Was Your Man” from one of its co-writers—wants damages and an injunction to block further distribution of “Flowers.”

Let’s break down the alleged similarities, starting with the lyrics.

The Lyrical Response: A Conversation, Not a Copy

The lyrics of “Flowers” provide a counterpoint to those in “When I Was Your Man,” creating a stark contrast between the two works. Mars reflects on lost love, expressing regret with lines like, “I should’ve bought you flowers,” and “held your hand,” wishing he had done more to keep his partner happy. In “Flowers,” Cyrus flips the script, singing, “I can buy myself flowers” and “I can hold my own hand,” signaling self-empowerment and independence in place of the regret and longing in Mars’s song. This call-and-response dynamic between the lyrics turns Mars’s message on its head, with Cyrus reclaiming agency after a withered relationship:

This lyrical back-and-forth makes “Flowers” the quintessential answer song. An answer song is written as a direct reaction to another artist’s work. It might reply to the lyrics, engage with the themes, or even extend the original story. Sometimes answer songs are playful, sometimes they’re serious, but they typically offer a fresh perspective, opposing viewpoint or a challenge to the message of the first song.

A Brief History of the Musical Comeback

Answer songs have a long tradition that can be traced back to the earliest forms of literature. The modern answer song took off with the rise in recorded music, especially in early R&B and country, where songs frequently served as replies to tracks performed by artists of the opposite sex.

While early answer songs weren’t particularly combative, that typically isn’t the case for modern hip-hop, in which artists often take jabs at each other through diss tracks. In 1984, the iconic “Roxanne Wars” erupted, kicked off by UTFO’s track “Roxanne, Roxanne” and Roxanne Shanté’s fiery response, “Roxanne’s Revenge.” This clash marked the beginning of the rap battle era, becoming one of hip-hop’s earliest rivalries and laying the groundwork for the battle rap culture that would follow. All told, the Roxanne Wars involved over 50 tracks from 35 different artists.

Sometimes answer songs are used to reimagine a character or story line from a prior song. Take David Bowie’s 1969 hit “Space Oddity,” which told the story of astronaut Major Tom, adrift in space, and “floating in a most peculiar way.” Bowie picked up the story again in 1980’s “Ashes to Ashes” with Major Tom channeling Bowie’s own struggles with addiction (“Strung out in heaven’s high / Hitting an all-time low”). In 1983, German new wave artist Peter Schilling offered his own take with “Major Tom (Coming Home),” imagining Major Tom drifting into outer space as radio contact breaks off with his ground control team (“‘Give my wife my love,’ then nothing more”).

Another famous example of a response song is Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” which not only responds to Neil Young’s criticisms of the South in “Southern Man” and “Alabama,” but calls out Young by name: “Well, I heard Mr. Young sing about her / Well, I heard ol’ Neil put her down / Well I hope Neil Young will remember / A Southern man don’t need him around anyhow.”

These examples—and literally thousands more—demonstrate how art so often not only builds on existing works but uses those works to create shared points of reference. When “Flowers” is viewed through this lens, its lyrics about buying one’s own flowers and holding one’s own hand serve as a clear counterpoint to “When I Was Your Man.” Far from copying to “avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh,” Cyrus and her co-writers engage with the original song to offer commentary, contrast, and reinterpretation—pillars of the transformative purpose that’s often so central to a copyright fair use analysis.

What About the Music?

While the lyrical similarities seem to have driven its lawsuit, Tempo Music also claims that the music is substantially similar as well. Among these allegations, the plaintiff points out that “the opening vocal line from the chorus of ‘Flowers’ begins and ends on the same chords as the opening vocal line in the verse of ‘When I Was Your Man’.” It isn’t particularly compelling.

Even more puzzling is the claim that a five-note portion of “Flowers” mimics “the basic melodic and harmonic design of E-D-C-E-F” at the end of a portion of the Mars song. I’m not even sure what that means; it sounds like an admission that the note sequence, while not identical, just “feels” similar. But because the case was filed in the Central District of California, the law of the Ninth Circuit applies. As that court held in a recent case involving Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” (where both parties’ songs contained similar arrangements of basic musical features including a pitch progression), “[a]llowing a copyright over this material would essentially amount to allowing an improper monopoly over two-note pitch sequences or even the minor scale itself, especially in light of the limited number of expressive choices available when it comes to an eight-note repeated musical figure.”

In the Cyrus case, it’s a four-note pitch sequence, but as musicologist Brian McBrearty noted in a lively exchange on X/Twitter this week with me and several music copyright experts (shout out to Joseph Fishman, Edward Lee and my buddy Kevin Casini), the timing and rhythm in both songs differ significantly, making any similarity in pitch less meaningful. And a four- or five-note pitch sequence isn’t inherently protectable in the first place. It’s also important to remember that music often follows recognizable patterns, as illustrated by the circle of fifths.

As the video below demonstrates, the circle of fifths shows the harmonic relationship between chords, making certain progressions sound natural to the ear. This helps explain why these patterns are so commonly used in countless songs across genres.

The Bottom Line

This probably doesn’t need to be said, but I’m good at that, so I’ll say it anyway: no art is created in a vacuum. Writers, filmmakers, and musicians all reference existing works in their own creations. This allows them to build connections with their audience or highlight a larger point by drawing parallels to familiar art. Whether it’s the internet meme, the innumerable pop culture callbacks in shows like The Simpsons or Family Guy, or intertextuality in literature, art builds upon art. More than that, it’s the reason art exists in the first place—to create shared experiences and draw connections to our collective cultural consciousness. That’s the reason copyright law recognizes fair use—and why Cyrus’s next response should be in the form of a motion to dismiss.

Finally, it’s worth noting that none of the original writers of “When I Was Your Man” are involved in this lawsuit. The only plaintiff is an investment fund that bought a share of the rights to the Mars song long after it was written. And, as Tempo Music itself admits, “Flowers” actually boosted streams of “When I Was Your Man” by nearly 20%. In the end, everyone wins—except for this lawsuit, which should be left to wither.

At least, that’s what I think. As always, let me know what you think in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the complaint to read while you’re busy holding your own hand.

View Fullscreen

1 comment

Aaron, excellent post! Great musicological analysis.