In 2006, the California Court of Appeal in Kirby v. Sega held that a video game’s depiction of pop singer Deee-Lite in a fanciful outer space setting is a “transformative use” protected by the First Amendment. On Wednesday of this week, the California Court of Appeal in No Doubt v. Activision held that a video game’s depiction of pop singer Gwen Stefani in a fanciful outer space setting singing songs she would never perform is not transformative, and therefore not protected by the First Amendment. And if the seeming inconsistency between those two rulings confuses the heck out of you, welcome to the club.

The tension between the right of publicity and the First Amendment is thicker than the“extenders” and “non-meat substances” in Taco Bell’s “seasoned beef.” I know this firsthand. A dozen years ago, my colleagues and I represented Dustin Hoffman in a lawsuit against Los Angeles Magazine, which took a picture of Hoffman as he appeared in Tootsie, superimposed his head on the body of a male model wearing the latest dress and high heels, and used him as an involuntary model in one of its fashion issues. We won the case at trial, and Hoffman was awarded $3 million dollars in damages (including $1.5 million in punitive damages). Unfortunately for us and our client, the Ninth Circuit later reversed, finding that the magazine’s conduct was protected by the First Amendment.

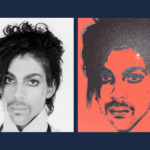

In the intervening years, the state of right of publicity law has only become more confusing, primarily as a result of California’s I-know-it-when-I-see-it concept of “transformative use.” This doctrine is meant to balance a publisher’s First Amendment interests against a celebrity’s interest in preventing the unauthorized use of his name and likeness for commercial purposes. An admirable enough goal, right? And the California Supreme Court purports to have reduced that goal to a fairly straightforward-sounding “test”: “when artistic expression takes the form of a literal depiction or imitation of a celebrity for commercial gain” without adding additional significant expression, the use is not “transformative” and is an infringement; but if the celebrity image is merely one of the “raw materials from which an original work is synthesized,” the work is transformative and is protected by the First Amendment.

I practice in this area of law, and I like to think of myself as reasonably bright, but I have yet to fully understand this so-called “test.” And judging by the way the cases have come down on this issue, courts are just as perplexed as I am:

Andy Warhol silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe: transformative.

Gary Saderup lithograph of the Three Stooges, as applied to t-shirts: not transformative.

Stylized painting of Tiger Woods (in triplicate) in front of the Augusta National Clubhouse: transformative.

Picture of Paris Hilton dressed as a waitress on a Hallmark card: not transformative.

That cleared it up for you, I’m sure.

So as you can see, the lines in this area of the law aren’t always so clearly drawn. Which brings us back to No Doubt and Activision.

We blogged about the No Doubt case last year, as part of a roundup of high-profile right of publicity actions involving video games. For those of you unfamiliar with the facts, Activision entered into a contract with No Doubt, which allowed the video game company to use the names and likenesses of the group in its Band Hero video game. As part of the agreement, Activision agreed to license no more than three No Doubt songs for the game. After the game was released, the band learned that Band Hero contained an “unlocking” feature that allows players to use No Doubt’s avatars to perform any of the songs included in the game, including songs that No Doubt claims it never would have performed. Female lead singer Gwen Stefani could even be made to sing a male voice. Unbeknownst to the band, Activision had hired actors to impersonate No Doubt in order to create the unauthorized performances. When Activision refused to remove the unlocking feature, No Doubt filed suit. Activision attempted to get the lawsuit thrown out, arguing that its use of the band was transformative and therefore protected by the First Amendment.

As broad and sacrosanct as the First Amendment may be, its protections may be waived by contract. No Doubt argued that Activision did just that by entering into a license that limits Activision’s right to use No Doubt’s likenesses in connection with songs approved by the band. The concurring opinion in the No Doubt case would have decided the case in favor of the band on these grounds, finding that Activision’s exploitation of No Doubt’s rights of publicity was subject to the terms of the agreement.

The majority opinion, on the other hand, sidestepped the contract issue and decided the case on First Amendment grounds. The court found that because Activision was using literal reproductions of the members of No Doubt performing rock songs — the same activity that made them famous — the fact that the avatars could be placed in fanciful settings “does not transform the avatars into anything other than exact depictions of No Doubt’s members doing exactly what they do as celebrities.” The court also found that Activision’s use of life-like depictions of No Doubt was motivated by its commercial interest in using the band’s fame to market Band Hero, and that the graphics and other background content were therefore secondary.

Compare this with what the Court said in rejecting Deee-Lite’s right of publicity claim in theKirby case: “[N]otwithstanding certain similarities, Ulala [the character allegedly based on Deee-Lite] is more than a mere likeness or literal depiction . . . Moreover, the setting for the game that features Ulala . . . is unlike any public depiction of [Deee-Lite].” In other words, while the Kirby case involved a video game character who was (allegedly) based on a celebrity, theNo Doubt case involves the explicit depiction of the celebrities themselves. And although Band Hero drops No Doubt into some fanciful and unusual settings, it fundamentally depicts them doing the same thing they usually do (i.e., playing music), as opposed to, say, playing the role of 25th century space-age reporters (as was the case for Dee-Lite/Ulala).

Of course, if the state judges who wrote the No Doubt decision need some reassurance, they can look no further than the federal courthouse on the other side of town. The day before theNo Doubt decision came down, the Ninth Circuit heard arguments in Keller v. Electronic Arts, a class action lawsuit brought by former Arizona State and Nebraska quarterback Sam Keller against Electronic Arts, claiming that EA had violated the right of publicity, of, well, every Division I collegiate football player in America by using their jersey numbers and other vital statistics in EA’s best-selling NCAA Football series. Like the judges in No Doubt, the district court judge in Keller found that EA’s NCAA Football game — which is marketed based on its realism — was not truly transformative, thereby defeating EA’s claim for absolute First Amendment protection. We’re waiting to see whether the Ninth Circuit will disagree and find that the players’ statistics were merely “raw materials” on which EA added significant additional expression.

I don’t take issue with the result in the No Doubt case, but I do find the California Court of Appeal’s attempt to reconcile all of its right of publicity opinions in this area to be rather disingenuous. While balancing the First Amendment rights of publishers against the publicity rights of celebrities is a worthy — and challenging — goal, ideally, the law should provide adequate guidance to individuals and companies who want to know how to comply with it. These new decisions only serve to further confuse an already exceedingly nuanced, complex, and frankly unpredictable area of the law (and, as our regular readers know, this is not the first time California courts have done such a thing in the last year).

Or maybe I’m just still bitter about the Dustin Hoffman thing.