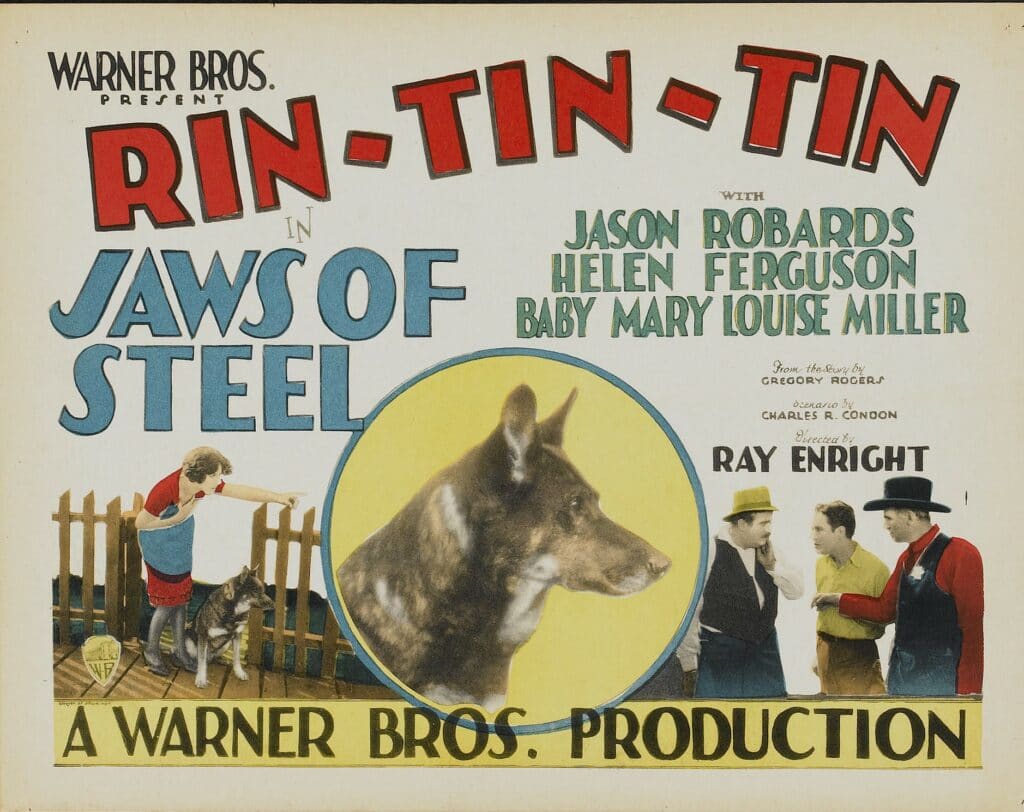

The studio argues that a complaint seeking an accounting of profits from its planned Rin Rin Tin film doesn’t arise under the Copyright Act.

Here’s a quick update on a case I first wrote about back in November involving Rin Tin Tin. He’s the canine film and television star made famous in the 1920’s, which makes him nearly 700 if you’re counting in dog years. In 2019, Warner Bros. announced plans to develop a new Rin Tin Tin motion picture, prompting plaintiff Scott Duthie to file a complaint against Warner and the producers of the project. Duthie’s lawsuit alleges that he owns a 50% copyright interest in the Rin Tin Tin character, but that Warner won’t acknowledge his rights or account for his share of the profits.

The chain-of-title set forth in Duthie’s complaint is relatively complicated, but it culminates in the allegation that plaintiff’s claimed co-owners—defendants Rin, Inc., Jeff Miller and Sasha Jenson—licensed rights to Warner without Duthie’s participation.

As I predicted, Warner’s first motion, filed yesterday, argues that the federal court doesn’t have subject matter jurisdiction to hear the case. As Warner points out, just because a lawsuit may involve a copyrighted work, this doesn’t mean that it necessarily arises under the Copyright Act.

Accounting Claims Between Copyright Co-Owners Don’t Arise Under Copyright Law

A case only “arises under” the Copyright Act if: (1) the complaint asks for a remedy expressly granted by the Copyright Act; (2) the complaint requires an interpretation of the Copyright Act; or (3) federal principles should control the claims.

Here, Duthie isn’t asserting that Warner has infringed any copyright interest he may have in Rin Tin Tin. Instead, he’s asking for an accounting of profits from the exploitation of the character.

According to Warner’s motion, Duthie is barking up the wrong tree by filing the case under the Copyright Act. It’s true that co-owners are required to account to each other for any profits earned from licensing or otherwise exploiting a copyright. However, as Warner correctly notes, this duty to account arises out of common law equitable principles, not copyright law.

Deciding the merits of Duthie’s claims is ultimately going to require a court to interpret a slew of contracts, assignments, judgments and other chain-of-title matters going back nearly a hundred years. But those claims won’t require the court to interpret the Copyright Act or any other federal principles. In other words, while Rin Tin Tin’s chain of title and ownership history may be a mess, it’s a mess that needs to be resolved under state law.

Accounting Rights Can Only Be Enforced Against a Co-Owner, Not a Licensee

Warner goes on to argue that even if the court did have jurisdiction, the plaintiff’s real dispute is with his other purported co-owners, not with Warner. While a copyright co-owner has a right to an accounting from his fellow co-owners, that right doesn’t extend to the co-owners’ licensee. Because Duthie doesn’t allege that Warner is a co-owner of the copyrights or that it has infringed those copyrights, the studio says it has no duty to account.

This is all pretty straightforward Copyright 101—707 if you’re counting in dog years. Unless the plaintiff can plead diversity or some other basis for federal jurisdiction, I expect the case against Warner to be tossed like a chewed-up frisbee.

A copy of the motion to dismiss is below:

UPDATE—On May 25, 2021, Duthie filed a voluntary dismissal of Warner, prior to even submitting an opposition to its motion. Could this be the rare example of a motion to dismiss the plaintiff actually thought was well taken? For now, the lawsuit proceeds against the remaining defendants, Rin, Inc., Jeff Miller and Sasha Jenson.

View Fullscreen