Using the DMCA to target hundreds of Wordle-likes, the publication claims exclusive rights in the game’s grid dimensions and color scheme.

Fresh on the heels of filing an infringement lawsuit against OpenAI, The New York Times Co. is flexing its copyright muscles once again, this time targeting the developers of hundreds of games inspired by Wordle, the popular word game the Times purchased in 2022. While some of these games are straight-up clones, others share little in common with Wordle beyond basic game mechanics, which, as I’ve discussed before, typically aren’t protected by copyright.

The Times’s DMCA Gambit

Rather than send targeted takedown notices directed at each offending clone, the Times dropped the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s equivalent of a chain reaction bomb against the developer of “Reactle,” an open-source Wordle clone that’s been forked and adapted nearly two thousand times to create various new games. The Times’s takedown notice to the popular code hosting platform Github (read here) claimed that because the Reactle repository includes “step by step instructions on how to create a clone of the Times’s copyrighted ‘Wordle’ game,” there is “no recourse but to remove the entire repository in order to stop the spread of willful copyright infringement.”

Among the casualties of this DMCA domino effect are a wide array of Wordle variants and spinoffs originally forked from Reactle. Some of the affected games are clones in different languages, while others adapt the Wordle game mechanics to subjects like Taylor Swift songs, hex color codes and poker hands. (Is a Wordless Wordle still a Wordle?) While the repository itself has been removed, you can view the archived page on the Wayback Machine to see a list and descriptions of some of the variants.

The Asserted Rights

So what exactly is the Times claiming to own? Per its DMCA takedown notice:

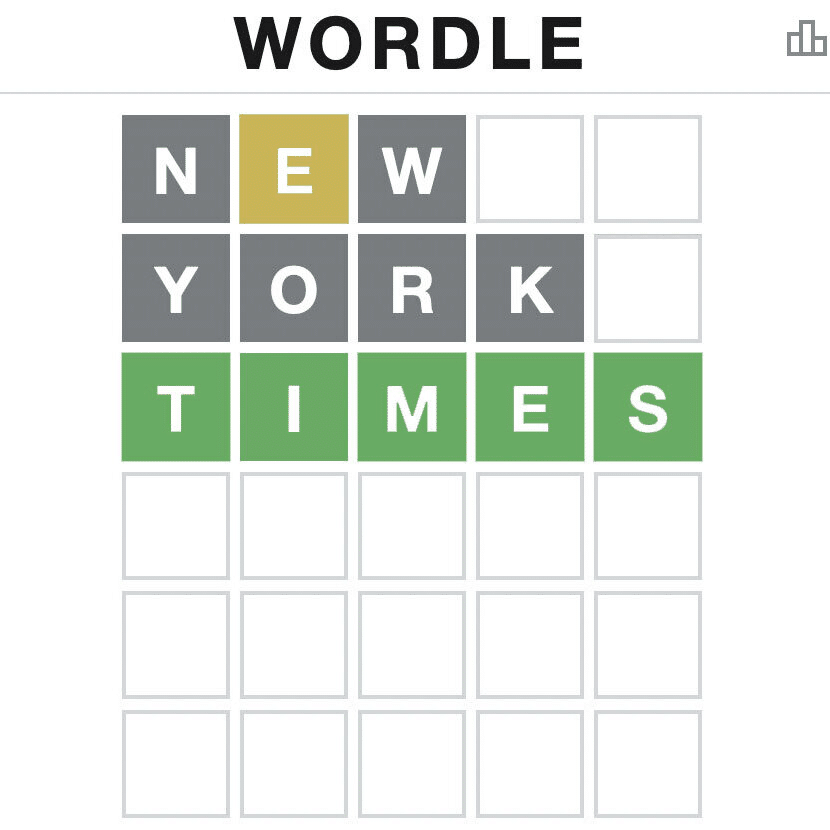

The Times’s Wordle copyright includes the unique elements of its immensely popular game, such as the 5×6 grid, green tiles to indicate correct guesses, yellow tiles to indicate the correct letter but the wrong place within the word, and the keyboard directly beneath the grid.

New York Times’s March 6, 2024 DMCA Notice

The surprising thing about this story isn’t just that The New York Times is aggressively policing its copyright against small-time noncommercial developers—it’s that the company is aggressively policing the copyright in a game that isn’t particularly original via a DMCA notice that arguably misstates the scope of its rights.

Wordle: An Evolutionary Approach

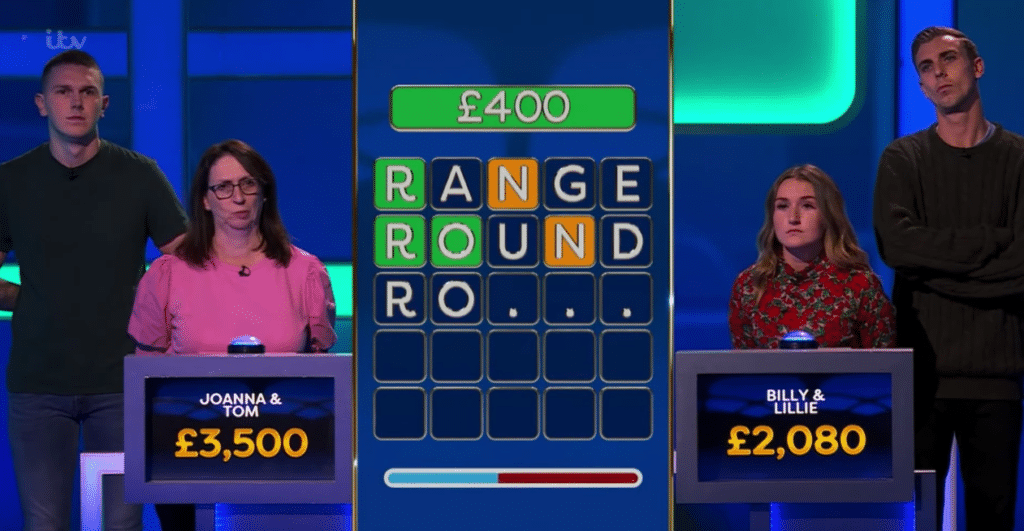

In a January 2022 article published as Wordle was going viral—before the Times purchased the game for a price “in the low seven figures”—the paper credited Wordle’s popularity to its simplicity: “To play the game, players guess a predetermined five-letter word in just six tries, similar to the process in ‘Lingo,’ a popular late ’80s game show. The yellow and green squares indicate that Wordle players guessed a correct letter or a combined correct letter and correct placement for that letter.”

The aforementioned Lingo first premiered in the U.S. in 1987 and has since been the subject of several reboots and dozens of international editions. The U.K. version even features the same color scheme as Wordle:

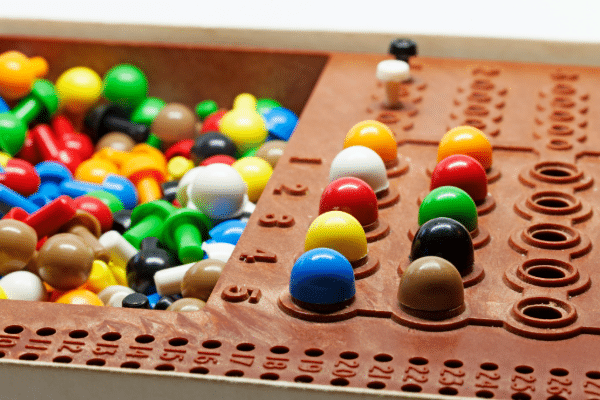

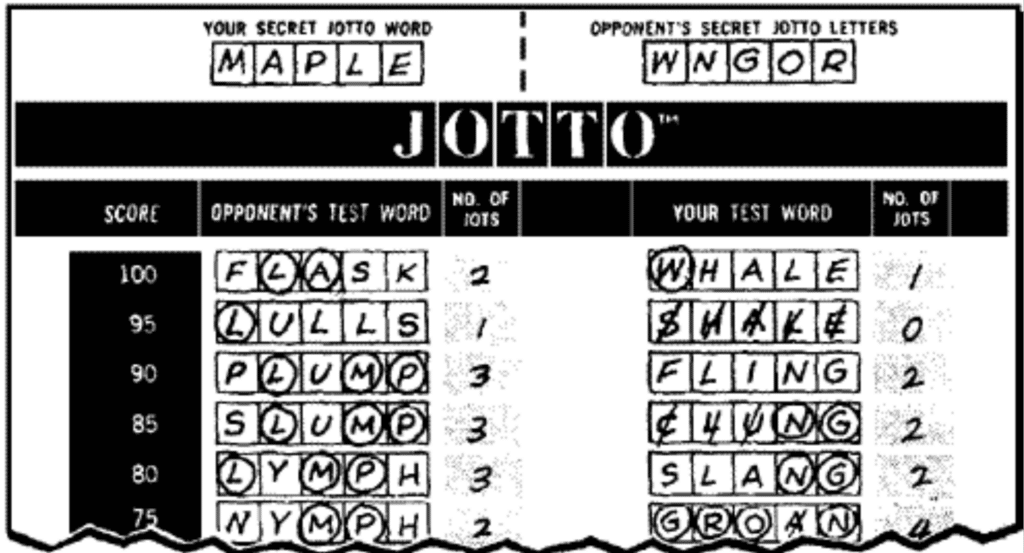

Of course, no game is created in a vacuum, and Lingo was itself influenced by earlier puzzle games like Mastermind, a codebreaking game that Wordle’s inventor, Josh Wardle, also credited as an early influence on his own creation.

Mastermind, in turn, is similar to even earlier paper and pencil word guessing games like Jotto and Bulls and Cows.

The Scope of Game Protection

As this little trip down memory lane shows, most games tend to evolve incrementally based on what’s come before. Lingo, Mastermind, Jotto, and Bulls and Cows all share similar gameplay rules and constraints. But these game mechanics are considered functional elements that fall outside the scope of copyright protection, because copyright doesn’t extend to systems, methods, or processes.

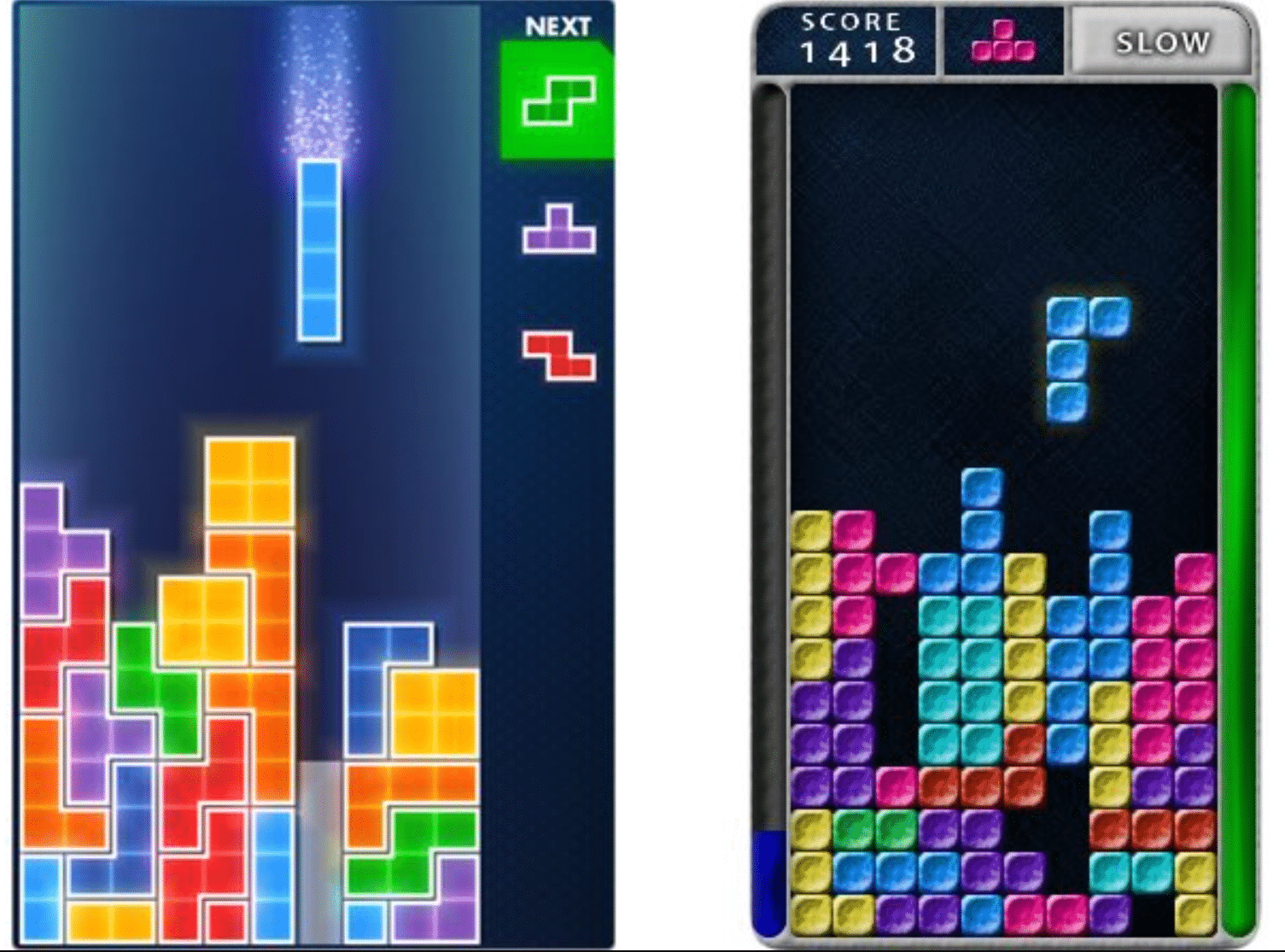

Other aspects of games, such as those related to graphic or similarly aesthetic elements as opposed to rules or systems, can be protected. For example, in a notable case involving Tetris, the court distinguished between that game’s unprotectable elements (the concept of vertically falling blocks that players need to rotate to form lines) with elements it found to be “expressive” (including the color and shape of the pieces and the display of “garbage lines”).

While the Times asserts that Wordle’s grid layout and color scheme likewise constitute original and expressive elements of its game, its claim is more tenuous both in light of Wordle’s similarities to earlier games like Lingo as well as the functional role these features serve within the particular game.

Expressive or Functional?

Grid Dimensions

In the Tetris case, the court counted the “dimensions of the playing field” among that game’s protectable elements because no rule of Tetris required that the playfield comprise a 20×30 grid. But Wordle’s grid dimensions are arguably a direct function of the game’s mechanics, with horizontal boxes dictated by the word’s length and vertical boxes dictated by the number of permitted guesses. Changing word lengths or guesses would dramatically alter the game’s difficulty, making Wordle’s grid dimensions more about functionality than creative expression.

As video game law expert Dan Nabel points out, another court opining on the protectability of playing field dimensions in a case involving an accused clone of the game Triple Town found that the use of a 6×6 grid was likely not an expressive choice: “A grid that is too small would make the game trivial; a grid that is too large would make it pointless.” The same could be said for Wordle’s 5×6 grid.

Color Scheme

The green and yellow color scheme is arguably more aesthetic than functional, but it’s not particularly original. Green is universally recognized as a signal for correct or positive outcomes, and yellow for a more intermediate status (Just check out your nearest traffic signal or battery health indicator.) As I noted above, Lingo uses that precise color scheme. Meanwhile, many of the “clones” targeted by the Times’s DMCA notice don’t.

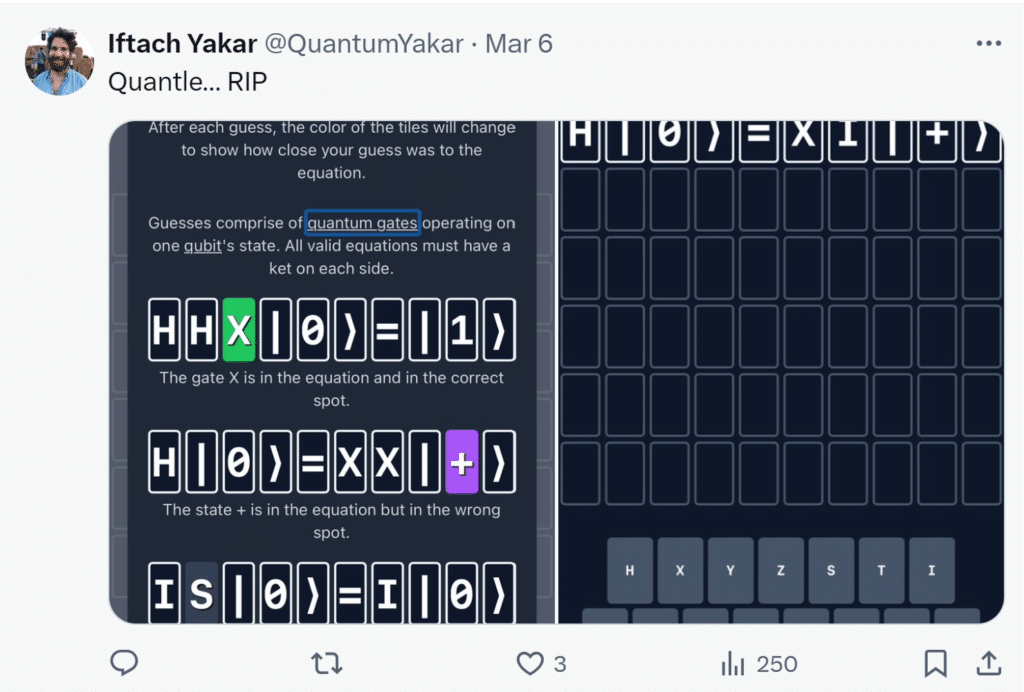

For example, one of the nuked games was Quantle, a Wordle variant in which the correct answers are quantum equations. Note that this one uses a 10×6 grid, a green/purple color scheme, and a non-QWERTY keyboard layout. In other words, it shares none of the so-called “unique elements” in which the Times claims copyright protection. It was still taken down.

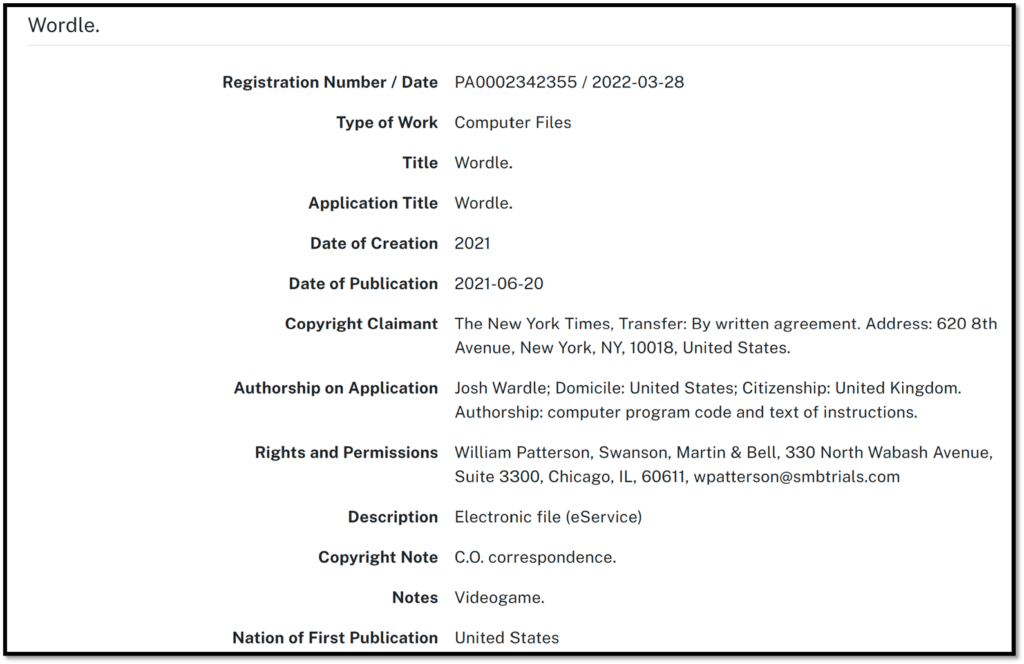

Wordle’s Copyright Registration

Even if we assume that the Wordle elements in which the Times claims protection are, in fact, unique and protectable, the company’s DMCA notice still appears to misstate the scope of its rights. As seen below, Wordle’s U.S. copyright registration limits the claimed authorship in the game to “computer program code and text of instructions.” This omission is important, because, per Copyright Office policy, the information provided in a copyright application defines the claim being registered. Without a registered copyright covering the visual elements cited in the Times’s DMCA notice, the legal basis for the company’s claims looks even more tenuous.

At a Loss for Wordles

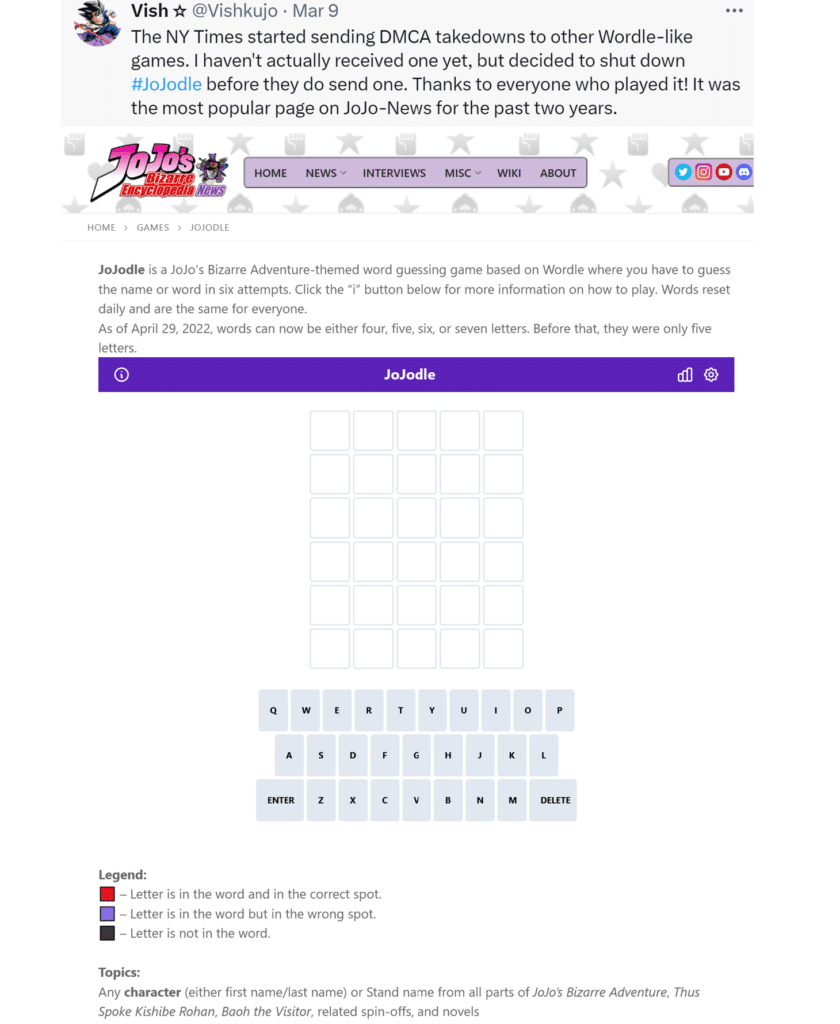

In recent days, numerous developers targeted by the Times’s DMCA notice have taken to social media to report that their own Reactle-built games have been shut down. That news has been met with backlash, with many pointing out that the Times only offers an English-language version of Wordle, while the cloned versions allow the game to be played using words in Korean, Bosnian, Yorùbá, and other minority languages. One not-for-profit version was dedicated to promoting a dying Scottish dialect. The Times shut it down anyway.

In a prepared statement, the Times said the company has no issue with people creating similar word games that do not infringe its Wordle “trademarks or copyrighted gameplay.” But the DMCA—which gives copyright owners a fast track to force platforms to remove allegedly infringing material—doesn’t apply to trademarks. And “copyrighted gameplay” isn’t really a thing. As I noted above, copyright doesn’t protect game mechanics or rules, just their particular expression. As far as I know, Reactle didn’t copy the source code for Wordle, which is the only aspect of Wordle’s authorship covered by the game’s copyright registration.

Many creators who disagree with the Times’s actions say they simply don’t have the resources to challenge the organization’s decision. Although filing a DMCA counter-notice provides a relatively easy way to dispute a takedown notice, it risks inviting a lawsuit. As a result, most, if not all, of those with targeted games aren’t fighting back. Some developers who haven’t yet received a DMCA notice for their Wordle-inspired games are even proactively removing them rather than risk potential legal action.

The Last Letter

The Times’s nuclear fission approach to the DMCA may successfully eradicate identical clones of Wordle, but not without also killing off guessing games devoted to Morse code, Mahjong hands and language preservation. It’s not a particularly good look for the Times, especially in light of the shaky foundation on which its claims of exclusive ownership rest and the iterative origins of its own game. An unsolicited Wordle of advice: In copyright law, as in life, just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

Of course, that’s just what I think. Inbounds or overreach? Let me know what you think in the comments below or via five-letter words @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the New York Times Co.’s DMCA notice:

View Fullscreen

1 comment

Great post – one issue though! I believe the registration for the computer software does include a claim to the display screens:

“As a general rule, a computer program and the screen displays generated by that program are considered the same work, because the program code contains fixed expression that produces the screen displays. If the copyright in the source code and the screen displays are owned by the same claimant, the program and any related screen displays may be registered with the same application. … If the applicant states “computer program” in the Author Created/New Material Included fields or in spaces 2 and 6(b), the registration will cover the copyrightable expression in the program code and any copyrightable screen displays that may be generated by that code, even if the applicant did not mention the screen displays and even if the deposit copy(ies) do not contain any screen displays.”

Compendium 721.10(A)