On January 1, 2025, the U.S. public domain officially welcomes the comic debuts of Popeye and Buck Rogers, alongside classic works by Faulkner, Hemingway, and landmark sound films from the year talkies took over. Here’s what it all means.

December is here, ushering in festive gatherings and holiday cheer—and for copyright enthusiasts, the countdown to one of the year’s most anticipated milestones: Public Domain Day. On January 1, 2025, a new crop of creative works from 1929 (along with sound recordings from 1924), will enter the public domain in the United States, unlocking countless possibilities for imaginative reinterpretation across genres.

Translation: prepare for a flood of low-budget slasher flicks.

Case in point is last month’s announcement of three new Popeye-inspired horror films, including Popeye the Slayer Man, set in an abandoned spinach cannery, and Shiver Me Timbers, featuring a meteor that “transforms Popeye into an unstoppable killing machine.” This trend follows the recent liberation of Steamboat Willie, which inspired horror reimaginings like Mouseboat Massacre and The Mouse Trap—the latter seeing Mickey’s earliest incarnation stalking teenagers at an arcade. And let’s not forget 2023’s Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, in which Milne’s honey-loving bear (sans red shirt) and his usually timid sidekick Piglet become feral killers after Christopher Robin abandons them for college.

This might be a good time to point out that U.S. copyright law does not, in fact, require adaptations of newly freed works to transform cherished childhood memories into homicidal maniacs. The public domain offers endless opportunities to breathe new life into timeless works—chainsaws optional.

A Farewell to Copyright

Literary Giants and Musical Masterpieces

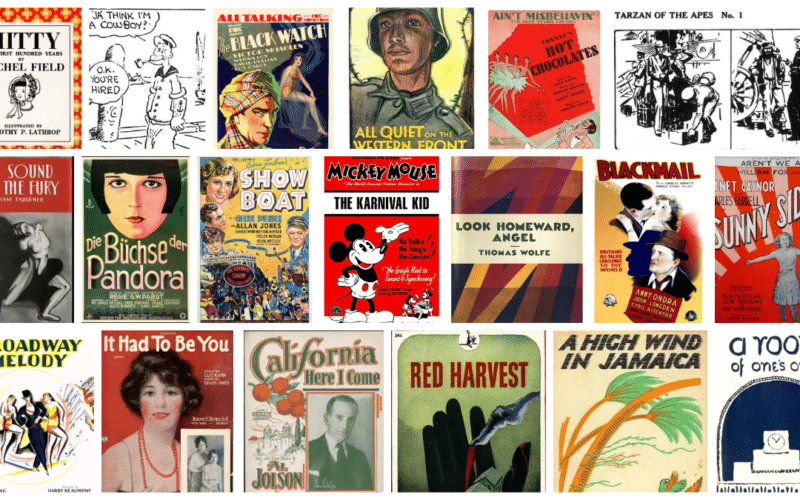

In addition to the sea-hardened Popeye the Sailor, the Public Domain Class of 2025 includes literary classics like Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, and Virginia Woolf’s essay A Room of One’s Own. The U.S. translation of Erich Maria Remarque’s seminal 1928 anti-war novel All Quiet on the Western Front will also enter the public domain on January 1, 2025—you may recall that protection in the original German version lapsed last year. The novel continues to be protected in Germany and other countries with copyright terms lasting 70 years after the author’s death, which includes much of the world.

Among the iconic musical works entering the U.S. public domain in 2025 are Fats Waller’s beloved composition “Ain’t Misbehavin‘” and the uplifting anthem “Happy Days Are Here Again,” famously used in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign. They’ll be joined by Cole Porter’s enduring jazz standard “What Is This Thing Called Love?” and “Tiptoe Through the Tulips,” which topped the U.S. charts in 1929 after appearing in the second musical talkie, Gold Diggers of Broadway. Decades later, Tiny Tim made it his signature song, turning it into a novelty hit in the 1960s. Sound recordings from 1924, including the first recordings of “Rhapsody in Blue” and “It Had to Be You,” are also set to expire, as I explain further below in the article.

From Silent to Sound

U.S. copyright protection is also set to expire for the Marx Brothers’ first film, The Cocoanuts, along with The Broadway Melody, which MGM touted as the first “All-Talking, All-Singing, All-Dancing” feature film. The latter topped the 1929 box office and won the Academy Award for Best Picture, though it hasn’t aged gracefully—Rotten Tomatoes ranks it as the worst of all 96 Best Picture winners.

History has been far kinder to Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl, two of the last great films of the European silent era, released as the film world transitioned to sound. Directed by G.W. Pabst and starring the iconic Louise Brooks, they’re celebrated for their daring exploration of gender, sexuality, and societal hypocrisy, exemplifying the avant-garde spirit of German Weimar cinema between the world wars.

A Public Domain Comeback

Interestingly, Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl are each about to make their second trip into the public domain. Initially distributed in the United States without the copyright notice required under the 1909 Copyright Act, the films were effectively thrust into the U.S. public domain. Their copyrights were later resurrected by the 1996 Uruguay Rounds Agreements Act (URAA), which restored protection for foreign works that remained under copyright in their source countries but had fallen into the U.S. public domain due to noncompliance with formalities like notice, registration, or renewal. The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) of 1998 further delayed their return to the public domain for another 20 years. Now, nearly three decades later, the films are set to reenter the U.S. public domain, this time for good.

Happy Public Domain Day 2025

Since its revival in 2019, Public Domain Day has introduced a steady stream of works into the U.S. public domain every year on January 1. In 2025, this will include all works first published in 1929. Note that works remain protected until the end of the calendar year. That’s why the earliest Popeye comic strips won’t enter the public domain until January 1, 2025, even though the character officially celebrated his 95th birthday on January 17, 2024.

I’ve listed dozens of other notable works entering the public domain at the end of this article. However, as always, Public Domain Day 2025 arrives with a number of significant works that deserve a closer look—as well as plenty of legal caveats, asterisks, and traps for the unwary. Read on for all the details.

The Sound Revolution: Talkies Take Over

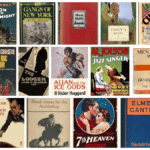

In my 2023 post on public domain works, I covered The Jazz Singer (1927), the first film with synchronized sound, and in my 2024 roundup, I highlighted Lights of New York (1928), the first “100% talkie.” But 1929 was the year synchronized sound truly took over, with talkies rapidly eclipsing silent films as the dominant force in cinema—despite concerns from some critics and filmmakers that sound would undermine the artistry of silent storytelling.

Alfred Hitchcock embraced the change with Blackmail, his first sound film, released in 1929 and now entering the public domain in 2025. Initially conceived as a silent film, Blackmail was converted mid-production to include synchronized sound. To address lead actress Anny Ondra’s heavy Czech accent, Hitchcock had English actress Joan Barry dub her lines live offscreen as Ondra lip-synced on camera. Like Harold Lloyd’s Welcome Danger, Blackmail was released in both sound and silent versions, as many theaters weren’t yet equipped to use the new technology. Studios also wanted to hedge their bets in the event sound films didn’t catch on with the public. They needn’t have worried. Audiences were enthralled, and box-office hits like On with the Show!, the first full-length color talkie, cemented sound’s dominance over cinema.

By late 1929, over 4,000 theaters had been wired for sound, and Hollywood’s biggest directors embraced the technology, with Cecil B. DeMille (Dynamite) and John Ford (The Black Watch) directing their first sound films. Director King Vidor released the musical Hallelujah, one of the first Hollywood films to feature an all-Black cast. In animation, Disney kept pace with groundbreaking shorts like The Karnival Kid, in which Mickey Mouse spoke his first words, The Opry House, in which Mickey’s gloves made their first feature appearance, and The Skeleton Dance, the inaugural Silly Symphony cartoon. These landmark works, alongside many others from this transformative year, will enter the public domain in 2025.

Comic Legends Enter the Public Domain

Popeye the Sailor: From Supporting Role to Superstar

This year’s public domain class also welcomes several iconic comic characters who made their debuts in 1929, starting with Popeye. The gruff sailor first appeared on January 17, 1929, as a minor character in E.C. Segar’s Thimble Theatre comic strip. The strip initially focused on Olive Oyl and her boyfriend, Ham Gravy, but Popeye’s scrappy, no-nonsense attitude quickly made him a fan favorite. He eventually replaced Ham as Olive’s love interest and became the centerpiece of the strip.

The Battle to Free Buck Rogers

Joining Popeye in the 2025 public domain are the earliest comic strips featuring sci-fi hero Buck Rogers. First introduced as “Anthony Rogers” in Philip Francis Nowlan’s 1928 novella Armageddon 2419 A.D. (already in the public domain), the character was renamed Buck and reimagined as a more action-driven hero for his January 1929 comic strip debut, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century A.D.

Buck Rogers’ path to the public domain has been anything but smooth. Years of legal disputes between the heirs of author Philip Francis Nowlan, newspaper publisher John F. Dille and film producers who claimed the character had already entered the public domain left Buck Rogers’ chain of title clouded in uncertainty. These conflicts deterred studios from adapting the property. Legal battles over control of the Buck Rogers trademark further complicated efforts to commercialize the hero for contemporary audiences. Come January 1, 2025, however, the earliest comic strips featuring the trailblazing space adventurer will officially and indisputably belong to the public. Buck and Popeye will also be joined by the first daily comic strip featuring Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes, part of a series that lasted for over forty years.

Tintin and a Global Patchwork of Copyright Terms

Another notable addition to the 2025 public domain is Hergé’s Tintin, the intrepid boy reporter who first appeared in serialized comic strips in the Belgian newspaper Le Petit Vingtième with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The series ran weekly from January 1929 to May 1930, but only the installments published in 1929 will be entering the U.S. public domain in 2025—and only the original French language versions. Tintin remains protected in France and other countries with copyright terms lasting 70 years after the author’s death, which includes much of the world. (The United States now uses a life + 70 copyright regime, but only for works created on or after January 1, 1978.)

IMPORTANT Public domain is country specific. Just because a work is in the public domain in the United States doesn’t mean it isn’t protected by copyright elsewhere—and vice versa. Check out my Copyright Myth Project for more.

Character Development: When Do Evolving Characters Enter the Public Domain?

Another important caveat is that characters that evolve over time don’t enter the public domain all at once. In a case involving the now-public domain Sherlock Holmes, the court in Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd. clarified that a copyrighted character begins to fall into the public domain when the first published story featuring that character enters the public domain. The Arthur Conan Doyle estate had argued that the Sherlock Holmes character would remain protected as long as any individual work depicting him was still under copyright, but the Seventh Circuit rejected this view.

The court held that once a work enters the public domain, “story elements—including characters covered by the expired copyright—become fair game for follow-on authors.” However, copyrightable aspects of a character’s evolution that appear in later still-protected works remain off-limits until those works enter the public domain.

For Popeye, this means that the 1929 version of the character becomes available on January 1, 2025. But like the earliest iterations of Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie and Winnie the Pooh in Now We Are Six, Popeye’s initial appearance lacks many of the traits most associated with him today. For example, Popeye’s iconic use of spinach as a source of superhuman strength—which King Features Syndicate claims boosted U.S. spinach sales by 33%—wasn’t introduced until 1932. And popular side characters like J. Wellington Wimpy, Popeye’s burger-mooching pal, and Swee’Pea, his adopted child, wouldn’t appear until later in the decade. These later elements remain protected under U.S. copyright law. The Hearst Corporation, King Features’ parent company, also owns several active registrations for Popeye-related trademarks, which may further limit use of the character in connection with commercial products.

Music Matters: Two Rights, Two Timelines

Determining the public domain status of music can also present challenges. As a refresher, every piece of recorded music has at least two different copyrights. The first is the copyright in the underlying composition, which protects a song’s lyrics and musical arrangement. The second is the copyright in the sound recording of that composition, protecting a specific performance captured by a recording artist. When you listen to music on the radio or a streaming service, you’re technically hearing both the composition and the sound recording of the composition.

Effect of the Classics Protection and Access Act on Public Domain for Pre-1972 Sound Recordings

The distinction between compositions and recordings is important because these two types of copyrighted works don’t enter the public domain at the same time. The copyright in a musical composition, like most other pre-1978 works, lasts for 95 years. For example, George Gershwin’s 1924 composition, “Rhapsody in Blue,” one of America’s most iconic classical pieces, entered the U.S. public domain in 2020, following 95 years of copyright protection.

But copyrighted sound recordings of “Rhapsody in Blue” follow a different timeline, thanks to the Classics Protection and Access Act, part of 2018’s Music Modernization Act. This legislation brought certain pre-1972 sound recordings within the scope of federal copyright for the first time and introduced an additional transition period of protection:

- Recordings first published before 1923: Entered the public domain on January 1, 2022.

- Recordings first published between 1923 and 1946: Gain an additional 5 years of protection, for a total of 100 years.

- Recordings first published between 1947 and 1956: Receive an additional 15 years of protection, for a total of 110 years.

- Recordings first fixed between 1957 and February 15, 1972: Remain protected until February 15, 2067.

As a result, sound recordings first published in 1929 will remain protected until 2030 (95 years + 5 additional years = 100 years). Meanwhile, earlier sound recordings published in 1924—like the original acoustic sound recording of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”—will enter the public domain on January 1, 2025, as they reach the 100-year mark. (Note that the more famous 1927 electrically recorded version of the same composition remains protected in the U.S. through 2027.)

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this year’s public domain class in the comments below or on social media @copyrightlately. In the meantime, here are just some of the notable works that you can copy, distribute, or adapt starting on January 1, 2025:

Notable Films Entering the Public Domain in 2025

- The Cocoanuts, directed by Robert Florey and Joseph Santley, the first film starring the Marx Brothers (Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Zeppo)

- Disney’s Plane Crazy (sound version), The Karnival Kid (in which Mickey Mouse speaks his first words), The Plowboy (first appearance of Horace Horsecollar), and The Skeleton Dance (the first Silly Symphony cartoon)

- Jungle Jingles, Race Riot, and Weary Willies, along with several other Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts

- Small Talk, the first Our Gang short to be released with sound

- Pandora’s Box (Die Büchse der Pandora) and Diary of a Lost Girl (Tagebuch einer Verlorenen), both directed by G.W. Pabst and starring Louise Brooks

- Say It with Songs, directed by Lloyd Bacon and starring Al Jolson (Jolson’s first full-length talkie)

- The Broadway Melody, directed by Harry Beaumont and starring Anita Page and Charles King (the first musical released by MGM and Hollywood’s first all-talking musical)

- Welcome Danger, directed by Clyde Bruckman and starring Harold Lloyd (Lloyd’s first sound film)

- Dynamite, directed by Cecil B. DeMille and starring Conrad Nagel (DeMille’s first sound film)

- On with the Show!, directed by Alan Crosland and starring Betty Compton and Arthur Lake (the first all-talking, all-color feature-length film)

- Hallelujah, directed by King Vidor and starring Daniel L. Haynes and Nina Mae McKinney (one of the first films with an all-Black cast produced by a major studio)

- Blackmail, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Anny Ondra (sound version voiced by Joan Barry; Hitchcock’s first sound film)

- Eternal Love, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring John Barrymore and Camilla Horn

- The Virginian, directed by Victor Fleming and starring Gary Cooper, Walter Huston, and Richard Arlen

- The Return of Sherlock Holmes, directed by Basil Dean and starring Clive Brook (the first sound film to feature Sherlock Holmes)

- Spite Marriage, directed by Buster Keaton and Edward Sedgwick and starring Keaton

- Bulldog Drummond, directed by F. Richard Jones and starring Ronald Colman

- The Three Masks (Les trois masques), directed by André Hugon and starring Renée Héribel, Jean Toulout and François Rozet (the first French sound film, though filmed in London)

- Behind That Curtain, directed by Irving Cummings and starring Warner Baxter and Lois Moran

- The Black Watch, directed by John Ford and starring Victor McLaglen and Myrna Loy (Ford’s first sound film)

- Where East Is East, directed by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney

- Land Without Women (Das Land ohne Frauen), directed by Carmine Gallone and starring Conrad Veidt (the first full-length German-speaking sound film)

- Show Boat, directed by Harry Pollard and starring Laura La Plante

- The Desert Song, directed by Roy Del Ruth and starring John Boles and Carlotta King

- Applause, directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Helen Morgan

- Disraeli, directed by Alfred E. Green and starring George Arliss

- Woman in the Moon, directed by Fritz Lang and starring Willy Fritsch and Gerda Maurus

- The Love Parade, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald

- Gold Diggers of Broadway, directed by Roy Del Ruth and starring Winnie Lightner and Nick Lucas

Notable Literature Entering the Public Domain in 2025

- The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner

- A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway

- Red Harvest, Dashiell Hammett

- All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque (first English translation)

- Berlin Alexanderplatz, Alfred Döblin

- A High Wind in Jamaica, Richard Hughes

- The Roman Hat Mystery, Ellery Queen (first Ellery Queen mystery)

- Dodsworth, Sinclair Lewis

- Hitty, Her First Hundred Years, Rachel Field

- A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf

- Good-Bye to All That, Robert Graves

- Look Homeward, Angel, Thomas Wolfe

- Mamba’s Daughters, DuBose Heyward

- The Bishop Murder Case, S. S. Van Dine

- Les Enfants Terribles, Jean Cocteau

- The Magic Island, William Seabrook

Notable Musical Compositions Entering the Public Domain in 2025

- “Honeysuckle Rose,” w. Andy Razaf, m. Thomas “Fats” Waller

- “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” w. Andy Razaf, m. Harry “Fats” Waller & Harry Brooks

- “What Is This Thing Called Love?,” w. & m. Cole Porter

- “Am I Blue?,” w. Grant Clarke, m. Harry Akst

- “Singin’ in the Rain,” w. Arthur Freed, m. Nacio Herb Brown

- “Tiptoe Thru’ the Tulips with Me,” w. Al Dubin, m. Joe Burke

- “Moanin’ Low,” w. Howard Dietz, m. Ralph Rainger

- “Happy Days Are Here Again,” w. Jack Yellen, m. Milton Ager

- “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling,” w. Billy Rose, m. Thomas “Fats” Waller & Harry Link

- “You Were Meant for Me,” w. Arthur Freed, m. Nacio Herb Brown

- “I’m a Dreamer, Aren’t We All?,” w. B.G. DeSylva & Lew Brown, m. Ray Henderson

- “Can’t We Be Friends?,” w. Paul James, m. Kay Swift

- “Without a Song,” w. Billy Rose & Edward Eliscu, m. Vincent Youmans

- “My Kinda Love,” w. Jo Trent, m. Louis Alter

Notable Sound Recordings Entering the Public Domain in 2025

- “Rhapsody in Blue,” Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra

- “It Had to Be You,” Marion Harris

- “California, Here I Come,” Al Jolson

- “Somebody Stole My Gal,” Ted Weems and His Orchestra

- “Somebody Loves Me,” Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra

- “Memory Lane,” Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians

- “What’ll I Do,” Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra

- “I Wonder What’s Become of Sally?,” Al Jolson

- “Wreck of the Old 97,” Vernon Dalhart

- “Jealous,” Marion Harris

- “June Night,” Ted Lewis and His Orchestra

- “Nobody’s Sweetheart,” Isham Jones and His Orchestra

- “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy,” Uncle Dave Macon

- “Mandalay,” Al Jolson

- “Everybody Loves My Baby,” Louis Armstrong with Clarence Williams’ Blue Five

- “How Come You Do Me Like You Do,” Marion Harris

1 comment

My comment is this is all done by highly paid lobbyists. It’s completely absurd the way lobbyists and bought off politicians just keep extending the dates when copyright is supposed to lapse. Look beneath the surface. Where do these laws come from? They are written by very rich lobbyists who sell their citizens out for a big paycheck, and they look to buy off some congressmen (Sonny Bono) and senators who obviously don’t care about the public good.

It’s a very corrupt system. It may be technically legal but no less corrupt than other countries.