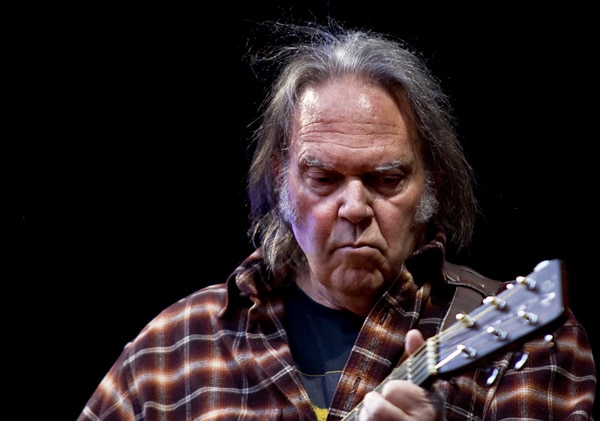

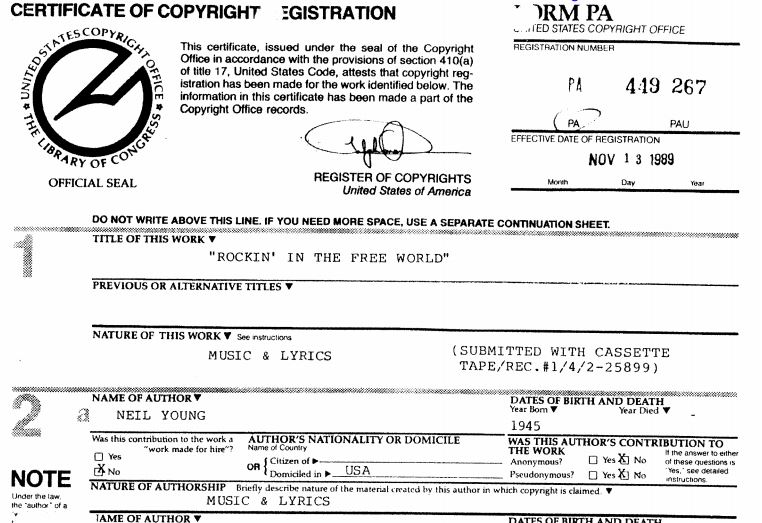

After objecting numerous times to the Trump Campaign’s use of his songs—particularly “Rockin’ in the Free World”—at political rallies, rocker Neil Young has pulled the trigger on a lawsuit. While Young asserts a straightforward claim for copyright infringement, his case may be complicated by a byzantine set of licensing rules and Justice Department consent decrees going back to the 1940s.

Before we dive into the complaint, let’s start with a few basics about copyrights in music. Copyright owners generally have the exclusive right to prevent third parties from reproducing, distributing or performing their copyrighted works without permission. But music is a special case. First of all, any piece of recorded music actually has two separate copyrights. There’s a copyright in the master sound recording (which is the particular version of a song performed by an artist), and a copyright in the composition (which is the underlying music and lyrics).

If someone wants to make copies or distribute a song as recorded, they’ll need to get a license from the owner of the sound recording. This is why it’s illegal to download songs on file sharing sites, and why record labels can send take-down notices when recordings are uploaded to YouTube. But sound recordings don’t enjoy the same “public performance” rights as other copyrighted works. While Congress did amend the Copyright Act in 1995 to cover the digital public performance of sound recordings, this amendment did not encompass traditional “terrestrial” (over the air) performances.

Had the Trump Campaign used Neil Young’s sound recordings in a recorded advertisement, the Campaign would have clearly needed to secure a “master use” license for the sound recording (as well as a “synchronization license” for the underlying composition). However, because Young alleges that the Campaign used his songs “Rockin’ in the Free World” and “Devil’s Playground” at a live political rally, the copyrights in those sound recordings weren’t technically infringed. As a result, Young’s complaint only asserts a claim for copyright infringement in the underlying compositions.

But even with compositions, it’s still tricky. Unlike other situations, in which copyrighted works are licensed on an individually-negotiated basis, public performances of musical compositions are covered by what’s called a “blanket license.” These licenses are issued by performing rights organizations (PROs) like ASCAP and BMI, and generally allow a licensee the right to publicly perform all of the compositions in that organization’s catalog.

The blanket license often makes sense. Imagine if a bar or gym that played music for its customers had to get a separate license from the owner of every composition that came out of the radio? Instead, these establishments enter into a blanket license with a PRO that covers millions of different songs.

Neil Young has previously recognized that the blanket licenses held by the Trump Campaign or the venues used for his rallies might prevent him from taking legal action when his songs were used without permission. Back in 2018, Young wrote a letter on his website criticizing Trump’s use of “Rockin’ in the Free World” at Trump’s public appearances, but appeared to concede that Trump was not committing copyright infringement: “Legally he has the right to do so,” Young wrote, “however it goes against my wishes.”

When “Rockin’ the Free World” was used as part of President Trump’s South Dakota rally, this past July, Young once again expressed his displeasure via Twitter:

But now, Young is doing more that voicing displeasure. He’s claiming that what the Trump Campaign is doing is not legal. In his August 4 complaint, filed in the Southern District of New York, Young specifically called out the Trump Campaign’s use of “Rockin’ in the Free World” and “Devil’s Sidewalk” at his June 20 rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and claimed that the Campaign did not have a license to use those works.

The Campaign does not now have, and did not at the time of the Tulsa rally, have a license or Plaintiff’s permission to play [“Rockin’ in the Free World” or “Devil’s Sidewalk”] at any public political event.

Complaint, Neil Young v. Donald J. Trump for President, Inc.

So, what’s changed? Well, it’s certainly possible that the Trump Campaign didn’t secure a “traveling license” from ASCAP to use that organization’s repertoire of songs at campaign stops in 2020. If not, then the public performance of Young’s music would be an infringement unless the venues at which Trump appeared had themselves secured a blanket license that covered the Campaign’s use.

It’s also possible, even if the venues had secured a blanket license, that this license excluded campaign events. ASCAP’s guidance on this issue states that “as a general rule, the licenses for convention centers, arenas and hotels exclude music use during conventions, expositions and campaign events.” (I’m not sure why a convention center would obtain a license that excludes conventions, but that’s another story).

Finally, it’s possible that Neil Young “opted out” of ASCAP’s blanket license. Both ASCAP and BMI appear to allow a songwriter or publisher to exclude specific musical compositions from a license granted to a particular political campaign if they object to the use.

The legality of this “political exclusion” is largely untested. ASCAP and BMI have been subject to consent decrees with the United States Justice Department since 1941. These agreements were designed to prevent anticompetitive behavior by the PROs and to ensure fair licensing rates throughout the industry. The decrees generally required ASCAP and BMI to offer their song catalogs on equivalent terms to any similarity situated party that wants to license them. In the event a mutually agreeable price can’t be negotiated, the parties can seek the assistance of a United States district court judge to determine an appropriate rate.

Because one of the purposes of the Justice Department consent decrees is to prevent ASCAP and BMI (or their member publishers) from “playing favorites” with respect to licensees, it’s unclear whether the consent decrees legally allow these PROs to exclude particular songs from blanket licenses based on a political objection.

According to BMI general counsel Stuart Rosen, who spoke to the New York Times on the subject, the ASCAP and BMI political exclusions don’t violate the consent decrees. “BMI does not remove a song from the license in order to achieve higher rates or for any reason other than that the rightsholders believe the association of their song with a campaign is an implied endorsement and diminishes the value of that work,” Rosen said.

This theory, however, is legally untested. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the Justice Department is currently reviewing the consent decrees to determine whether they should be modified or perhaps eliminated altogether.

Given the lack of clarity on the blanket license’s political exclusion, songwriters who have objected to the use of their music in political campaigns have often relied on additional theories other than copyright.

One argument has been that the unpermitted use of a song at a campaign rally constitutes an “false endorsement” under the Lanham Act, by implying that the songwriter or artist agrees with the campaign’s political message. This, however, is a relatively untested legal theory. Artists have also contended that the use of their voices violates state-specific right of publicity laws, but these claims are likely preempted by the Copyright Act. Interestingly, Young’s complaint against the Trump Campaign foregoes these other claims and only asserts a single cause of action for copyright infringement.

In addition to Young, artists from Rihanna to Brendan Urie to the estate of Tom Petty have publicly expressed their anger at the Trump Campaign’s use of their music and have demanded that the Campaign “cease and desist”—although no other artist has taken any formal legal action as of yet. In late July, dozens of popular artists working with the Artist Rights Alliance, including Mick Jagger, Lorde and R.E.M., signed an open letter calling upon politicians to stop using their music without permission. The letter urged major political party committees in the United States to “establish clear policies requiring campaigns to seek consent of featured recording artists, songwriters and copyright owners before publicly using their music in a political or campaign setting.”

The Artist Rights Alliance asked for a response to its open letter by August 10, but so far it does not appear that the organization has received anything back from any of the political parties or campaigns. Meanwhile, Neil Young’s lawsuit against the Trump Campaign is just getting started. While it may be too late to get clarity on these important copyright issues in time to impact the current presidential election cycle, they will hopefully be resolved soon. After all, 2024 is just around the corner.

UPDATE—On December 7. 2020, Neil Young filed a notice of dismissal of his case against the Trump Campaign. It’s unclear whether the parties’ settled or whether Young simply decided not to pursue the case further.