In a 30-page order, the district court largely denies both parties’ motions for summary judgment, finding triable issues on substantial similarity and fair use.

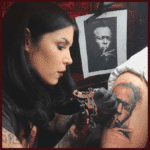

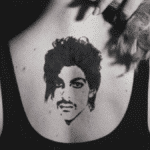

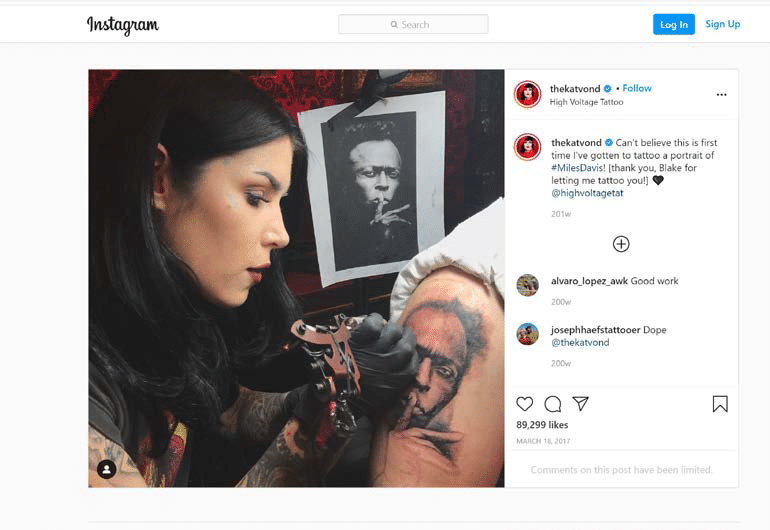

When lighting technician Blake Farmer got a tattoo of Miles Davis from celebrity tattoo artist Kat Von D in 2017, he never could have imagined that the image on his right arm would one day become Exhibit A in a copyright infringement lawsuit. The case raises an issue that, as far as I can tell, has never before been asserted in court, let alone decided: does a tattoo artist commit copyright infringement by using a copyrighted image as a reference when creating a client’s tattoo?

Now, five years later, a federal judge in Los Angeles has ruled that it’s up to a jury to determine whether a tattoo that permanently resides on Blake Farmer’s skin is an act of infringement or a fair use. What could possibly go wrong?

Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg—A Quick Recap

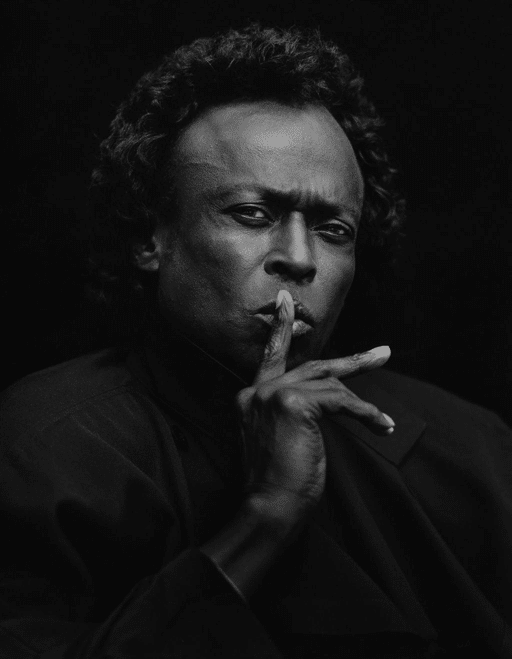

As I wrote last year, the lawsuit was filed by photographer Jeff Sedlik, who owns the copyright in this photo of legendary jazz musician Miles Davis:

The principal defendant in Sedlik’s lawsuit is Katherine Von Drachenberg, better known as Kat Von D. Sedlik alleges that Von D infringed the copyright in his photo by tattooing a reproduction of the Miles Davis image onto the skin of Blake Farmer and then displaying images of the tattoo on her social media accounts.

In March, the parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment: Sedlik sought a ruling that his copyright had been infringed as a matter of law, while Von D (along with defendants KVD, Inc. and High Voltage Tattoo) asked the court to determine that the use of Sedlik’s photo as a reference image qualified as a fair use of the copyrighted work.

The Court’s Summary Judgment Ruling

After taking the parties’ cross-motions under submission (and without hearing oral argument), Central District of California Judge Dale Fischer issued an order yesterday on the motions (read here).

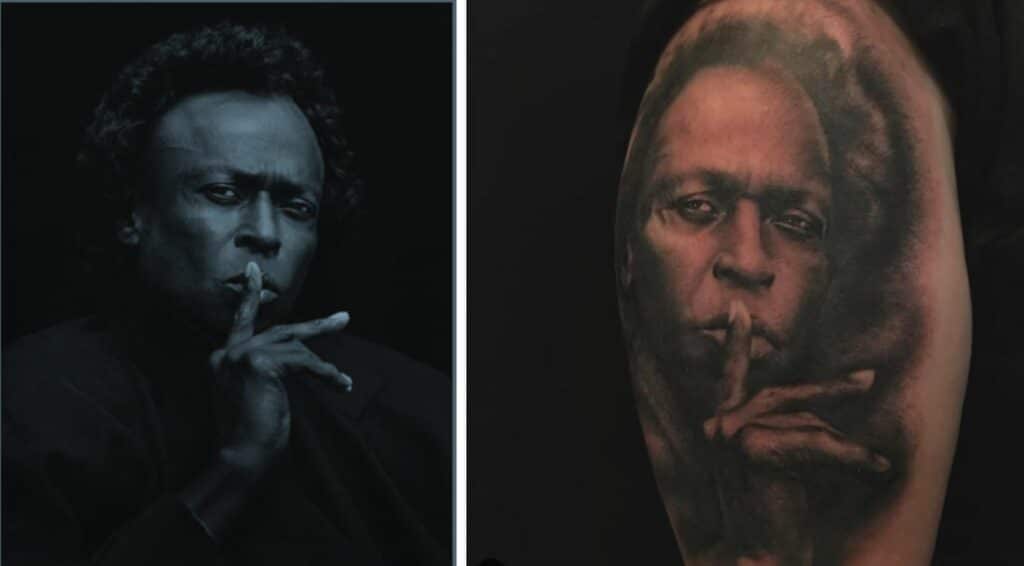

While the court’s opinion is quite detailed, the judge ultimately found that most of the contested issues in the case should be left to a jury. There are two main issues presented in the ruling—whether Kat Von D used copyrightable elements from Sedlik’s image to create her tattoo, and if so, whether her actions in doing so are protected by copyright law’s fair use doctrine.

Blake Farmer isn’t a party to the lawsuit, so he apparently gets to wait around to see if a jury will require him to amputate his right arm. (Relax, that’s a joke. At most it would be subject to impoundment, and he’d still be free to use his other arm.) 🤪

Substantial Similarity

On Sedlik’s affirmative motion for summary judgment, there was no dispute that the photographer owned a valid copyright in his photo of Miles Davis or that the defendants used the image as a reference in creating the tattoo. Instead, the defendants focused their opposition on arguing that they didn’t copy any “protectible elements” from Sedlik’s copyrighted photograph.

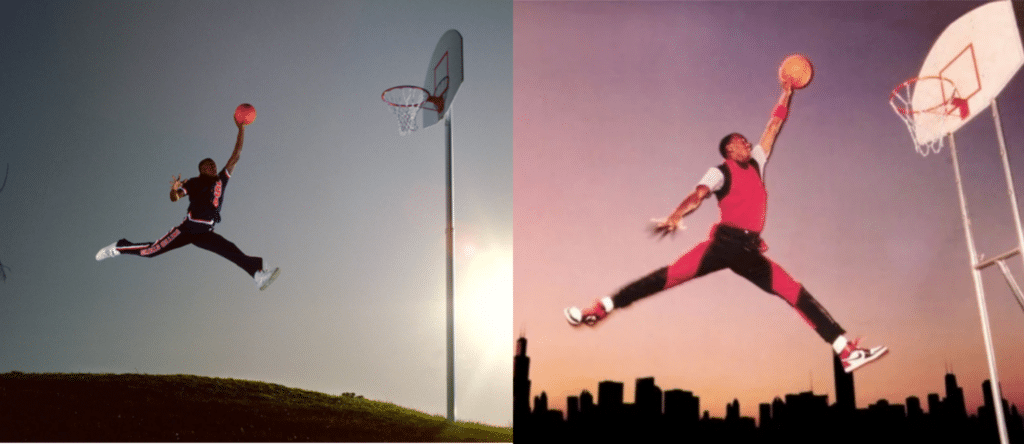

Unlike literary works such as novels, plays and motion pictures, the Ninth Circuit previously held in Rentmeester v. Nike that the various elements that make up a photo (pose, lighting, camera angle, etc.) can’t be dissected into protected and unprotected elements. A sufficiently original “selection and arrangement” of these elements is entitled to protection, but a copied photo and the original need to be substantially similar with respect to this combination to support an infringement claim.

In Rentmeester, the Ninth Circuit was able to find that the two images at issue in that case were so “unmistakably different” in material details that no ordinary observer of the works (i.e., a jury) could find infringement.

There are certainly noticeable differences between Sedlik’s photo of Miles Davis and Kat Von D’s tattoo—such as the light and shading on Davis’s face, the hairline on his head, and the background of the two images—but they’re more subtle. As a result, the Sedlik court found that the question of substantial similarity should be left to the jury.

Fair Use

The defendants’ main argument in support of their affirmative summary judgment motion was that Kat Von D’s use of Sedlik’s photo to create her tattoo constituted fair use. Here too, the court said this was a question for the jury.

This aspect of the court’s ruling is somewhat surprising, because as far as I can tell, there really aren’t any factual disputes left to resolve. In last year’s Google v. Oracle decision, the Supreme Court held that fair use is a “mixed question of fact and law,” which means that while courts should defer to a jury’s finding of underlying facts, the ultimate question of whether those facts amount to a fair use is a legal question for judges to decide.

I’ll quickly run through the court’s assessment of the traditional four factor fair use test, along with a “bonus” factor:

The Purpose and Character of the Use

The first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use,” typically includes an inquiry into whether the defendant’s work is “transformative” of the plaintiff’s. The Ninth Circuit is often seen as one of the most liberal in the nation when it comes to deciding whether a new work has altered an original work with “new expression, meaning or message” in a manner that is sufficiently transformative of the original.

Here, the defendants submitted a declaration from Blake Farmer explaining his purpose in choosing the image of Miles Davis and the personal significance he attached to the image when he asked Kat Von D to permanently apply it to his skin. However, the court found that “the subjective belief of the wearer of a tattoo as to the tattoo’s purpose is not dispositive of transformativeness.” The court also rejected the argument that the tattoo created an inherently different meaning “by virtue of its location on the human body.”

The court did find more convincing the defendants’ argument regarding the visual modifications made to the original Davis image resulting from Kat Von D’s artistic technique in inking the tattoo, but ultimately found that the issue of transformativeness “is more appropriately left to a jury.”

The court also found a dispute as to whether or not the defendants’ purpose in using Sedlik’s image was “commercial.” On one hand, neither Kat Von D nor High Voltage charged Farmer for inking the tattoo, but Sedlik countered that the defendants received an indirect economic benefit by posting photos of the tattoo on their various social media platforms.

The Nature of the Copyrighted Work and the Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

The court split on the second and third fair use factors. Examining the “nature of the copyrighted work,” the court found that while Sedlik’s image was a work of creative expression as opposed to a factual work, the fact that it had been published several decades ago weighed in favor of the defendants’ tattoo being a fair use. However, the court found that the “amount and substantiality of the portion used” weighed against fair use and in favor of Sedlik. As in most fair use situations, these two factors don’t do much heavy lifting in this case.

The Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market for or Value of the Plaintiff’s Copyrighted Work

In examining the fourth fair use factor (the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the plaintiff’s copyrighted work), the court found “no evidence that the Tattoo is a substitute for the primary market” for Sedlik’s original image, but that there was a triable issue as to whether there is a market for “future use” of the image on tattoos. The court rejected the suggestion that “tattooists, unlike other visual artists, should as a matter of law be immune from licensing requirements, or that the procedures of the tattoo industry cannot change to accommodate the time needed to obtain a license if required.”

A Non-Statutory “Fifth” Factor?

The defendants’ lawyers also asked the court to consider a non-statutory fair use factor outside of the traditional four: “an individual’s fundamental rights to bodily integrity and personal expression.” The defendants argued that “Holding tattoo artists civilly liable for copyright infringement will necessarily expose the clients of these artists to the same civil liability anytime they choose to get tattoos based on copyrighted source material, display their tattooed bodies in public, or share social media posts of their tattoos. That is not the law and cannot be the law.”

I previously wrote about some of the interesting (and potentially troubling) implications of a ruling that could ostensibly give copyright owners control over the bodies of tattoo clients, but the court decided not to go there. Given the triable issues the court found with respect to the statutory factors, it declined to address the defendants’ non-statutory arguments, again reiterating that “the issue of fair use as to the Tattoo and the associated social media posts is more appropriately left to a jury.” Lucky them.

Odds and Ends

There were a couple of issues that the court found it was able to decide as a matter of law. Summary judgment was granted in favor of Kat Von D’s company, KVD, Inc., based on a lack of evidence that the company had anything to do with the allegedly infringing tattoo or its promotion on social media.

The court also granted summary judgment for the defendants on Sedlik’s claim for violation of 17 U.S.C. § 1202, which prohibits the knowing removal or alteration of “content management information” (CMI) with the intent to conceal infringement. CMI generally extends to such information as the photographer’s name and any copyright notices appearing on the photo. Here, the court found that Sedlik didn’t introduce evidence that any CMI was present on the image of Miles Davis when it was sent to the defendants or that the defendants intentionally removed it.

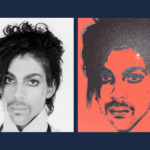

What About Warhol?

Meanwhile, the elephant in the room in this case is the Supreme Court’s upcoming ruling in Warhol v. Goldsmith. While the 30-page ruling in Sedlik didn’t once mention it, the shadow that the Supreme Court will soon cast on the fair use landscape—especially as it applies to allegedly transformative uses of photographs—can’t be ignored.

There’s no question that the fair use issues the court reserved for the jury in Sedlik are often decided by judges themselves. But here, Judge Fischer may have purposefully decided to take a more conservative “wait and see” approach by refraining from making legal rulings that could be later called into question or subject to reevaluation in light of Warhol.

Take a look at the decision for yourself and let me know what you think, either in the comments below or on social media @copyrightlately.

View Fullscreen