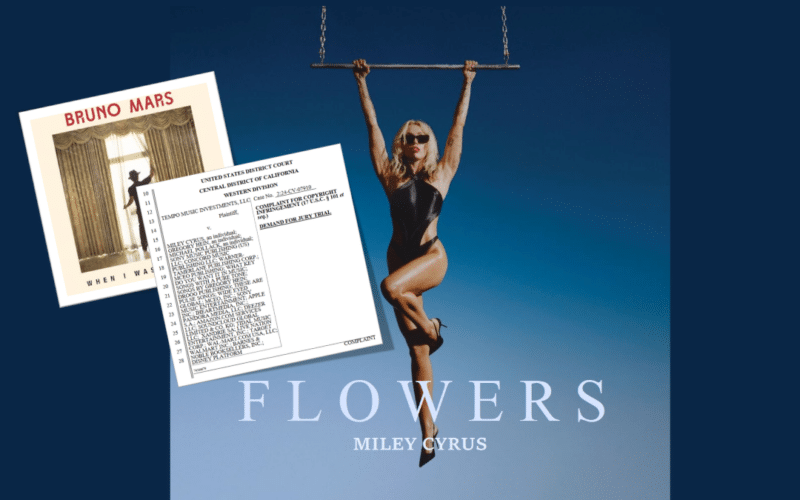

Miley Cyrus’s new motion to dismiss the “Flowers” lawsuit highlights the Ninth Circuit’s flawed approach to copyright standing for co-owners.

The lawsuit accusing Miley Cyrus of copying Bruno Mars’s “When I Was Your Man” to create her hit “Flowers” deserves to be dismissed—but not for the reasons laid out in a new motion filed this week by Cyrus and her co-writers.

As I’ve written before, Miley Cyrus’s “Flowers”—a textbook example of an “answer song” in response to “When I Was Your Man”—almost certainly qualifies as a fair use of Bruno Mars’s original. However, according to her motion to dismiss (read here), plaintiff Tempo Music Investments’ case suffers from a “fatal flaw” that dooms it even before issues like substantial similarity and fair use come into play. Cyrus and her co-writers argue that because Tempo owns only a fractional share of “When I Was Your Man”—acquired from co-author Philip Lawrence—it can’t sue for infringement without involving the other co-owners, including Bruno Mars, who aren’t part of the case.

A Fatal Flaw?

The defendants’ argument does indeed highlight a flaw—but it’s one rooted in fifteen years of muddled Ninth Circuit precedent. By misapplying principles of divisibility, transferability, and standing, the Hollywood circuit has sent mixed signals about the rights of co-owners to sue third-party infringers. The result is a framework that creates impractical outcomes and undermines copyright enforcement—particularly in the music industry, where fractional ownership is the norm.

Without meaningful enforcement rights, jointly owned works risk becoming legally vulnerable, especially when one or more co-owners are disinterested, unavailable, or unwilling to join an infringement claim. Ironically, these barriers could also ensnare some of the defendants in the “Flowers” case, including major record companies and music publishers, which frequently hold—and sue based on—fractional shares of songs. Perhaps that’s why most of the defendants opted to file an answer (read here) rather than join Cyrus’s motion to dismiss. Still, all 29(!) defendants are represented by the same legal team—led by the excellent Peter Anderson—which makes the strategy somewhat surprising. Indeed, as I’ll discuss, at least one of the non-joining defendants has actually taken a position contrary to Cyrus’s in other cases.

The Standing Argument in the “Flowers” Case

In their motion to dismiss, Miley Cyrus and her co-writers argue that Tempo Music’s lawsuit is fundamentally flawed under established Ninth Circuit precedent. The defendants contend that Tempo’s claim fails because its rights are based on a fractional interest in “When I Was Your Man” acquired from co-author Philip Lawrence—a transfer that did not include rights held by the other co-owners, including Bruno Mars.

The Copyright Act limits infringement claims to the “legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right.” The defendants argue that under Ninth Circuit law, a co-owner can’t unilaterally transfer exclusive rights without the consent of all other co-owners. As a result, the motion contends that the rights acquired by Tempo are deemed non-exclusive, preventing the company from filing an infringement lawsuit.

The motion further asserts that even if Lawrence’s assignment to Tempo purported to grant exclusivity, the transfer couldn’t override the independent rights of the other co-owners to exploit the song without Tempo’s involvement. The defendants say that this lack of exclusivity renders the lawsuit fatally flawed, as Tempo lacks the standing required to pursue infringement claims. Therefore, the motion concludes, the lawsuit should be dismissed outright.

How Copyright Law Handles Co-Ownership

While it’s true that one co-owner can’t transfer the exclusive rights of another co-owner, the Copyright Act of 1976 made copyrights divisible, transforming copyright ownership into a bundle of discrete exclusive rights that can be independently owned, licensed, or transferred. This means that each co-owner has the independent right to use, license or transfer their undivided fractional interest in the work without needing the consent of the other co-owners. This includes the right to enforce the copyright—a principle enshrined in section 501(b) of the Copyright Act, which states that “[t]he legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right under a copyright is entitled … to institute an action for any infringement of that particular right committed while he or she is the owner of it.”

At the same time, there are limitations on what a co-owner can do. While copyright owners can convey any of their own rights to others, a co-owner can’t transfer the interests of fellow co-owners without their express written consent. This restriction prevents actions that would impair the rights or diminish the value of the copyright to other co-owners. For example, a co-owner may unilaterally grant a non-exclusive license to third parties, as this does not interfere with the other co-owners’ ability to license or use the work themselves. However, a co-owner can’t unilaterally grant an exclusive license because such a license would necessarily restrict the rights of other co-owners to exploit or license the same work, effectively impairing the value of their ownership share.

This principle ensures co-owners can act independently to protect their rights, but applying it consistently across circuits has proven more challenging.

A Tale of Two Circuits

The Second Circuit has managed to interpret these principles with relative clarity. In its 2007 opinion in Davis v. Blige, the court reaffirmed that co-owners of an exclusive right may bring an infringement action without involving the other co-owners. This interpretation aligns with the Copyright Act’s framework of divisibility, which allows exclusive rights to be enforced independently by their holders. Importantly, Davis emphasized that a co-owner’s independent right to enforce the copyright is subject to a duty to account for profits to the other co-owners. This ensures that all co-owners receive their proportional share of any earnings from enforcing the copyright, preserving the balance of the broader ownership structure.

But what about the Ninth Circuit? Decidedly more messy.

You May Ask Yourself, “Well, How Did We Get Here?”

Sybersound: Co-Owner Enforcement Rights Take a Hit

The Ninth Circuit’s restrictive approach to co-owner standing began in 2008 with Sybersound Records, Inc. v. UAV Corp. Sybersound, a karaoke producer, alleged that its competitors infringed its copyrights by distributing karaoke tracks without proper synchronization licenses for the underlying music. Sybersound claimed standing to sue as an exclusive assignee and licensee of karaoke-use rights acquired from TVT Music Publishing, one of the co-owners of the works.

The court disagreed, holding that TVT, as a co-owner, couldn’t unilaterally transfer exclusive rights without the consent of the other co-owners. Without unanimous consent, the court reasoned, TVT’s transfer could only convey non-exclusive rights, which failed to satisfy the Copyright Act’s requirement that only the legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right can sue for infringement.

The Ninth Circuit’s holding likely stemmed from a misinterpretation of the rights TVT transferred to Sybersound. Rather than focusing on whether TVT properly conveyed its own exclusive rights in the karaoke-use interest, the court instead emphasized TVT’s inability to affect the rights of its co-owners. This reasoning erroneously conflated two distinct concepts: a co-owner’s ability to grant its own exclusive rights (allowed) and the unilateral transfer of collective rights in the work as a whole (not allowed).

While the court cited Davis v. Blige and acknowledged that co-owners generally have an independent right to use, license, and enforce their share of a copyright, it undermined this principle by confusing the exclusive nature of rights granted to a licensee with the non-exclusive nature of co-owner rights relative to one another. This narrow interpretation effectively nullified Sybersound’s ability to enforce its share of the copyright, imposing a unanimity requirement unsupported by the Copyright Act. Indeed, the 1976 Act’s divisibility framework explicitly allows copyright owners to freely and independently transfer their share of any exclusive right.

Corbello: A Glimpse of Clarity

Seven years later, the Ninth Circuit revisited the issue in Corbello v. DeVito, a case involving the Broadway musical Jersey Boys. The lawsuit stemmed from a memoir co-written by Tommy DeVito, a founding member of The Four Seasons, and Rex Woodard, Corbello’s late husband and DeVito’s co-author. After Woodard’s death, Donna Corbello inherited his share of the memoir’s copyright. The dispute arose when DeVito granted his bandmates Frankie Valli and Bob Gaudio the right to use the memoir in developing Jersey Boys without Corbello’s consent, sparking a lawsuit.

The Ninth Circuit characterized the operative agreement as a transfer of DeVito’s derivative work right in the memoir to Valli and Gaudio, rejecting the argument that Sybersound barred such an assignment. The court clarified that under the Copyright Act’s divisibility framework, co-owners may independently transfer their proportional exclusive rights, provided the transfer doesn’t impair the rights of other co-owners.

In rejecting an interpretation of Sybersound that would preclude DeVito, as a co-owner, from transferring exclusive rights in his proportional interest in the memoir to Valli and Gaudio, the court explained that construing “exclusive rights” as belonging only to sole owners would “run directly contrary to another well-settled principle of copyright law: the right of one joint owner to sue third-party infringers without joining any of his fellow co-owners.”

While the three-judge panel in Corbello lacked authority to overrule Sybersound, it mitigated the earlier decision’s harshest effects, marking a much-needed departure from the restrictive logic of the earlier case.

Tresóna: Back to Confusion

Unfortunately, this progress proved temporary. In 2020’s Tresóna Multimedia, LLC v. Burbank High School Vocal Music Association, the Ninth Circuit revisited its earlier reasoning from Sybersound, reaffirming some of the same limitations that had previously drawn criticism. Tresóna, a licensing company, claimed standing to sue over the use of four songs performed by high school show choirs without proper synchronization licenses. Tresóna’s rights to these songs were derived through assignments from co-owners of the respective copyrights.

The court rejected Tresóna’s claims for three of the songs, holding that the company lacked standing because the rights it acquired weren’t exclusive, as required under § 501(b) of the Copyright Act. The court reasoned that without unanimous consent from all co-owners, an individual co-owner could not transfer exclusive rights to Tresóna, reducing its rights to those of a non-exclusive licensee, which are insufficient to sustain an infringement suit. For the fourth song, the court found the use qualified as fair use, further defeating Tresóna’s claims.

While the Ninth Circuit cited Corbello approvingly, it ultimately limited that decision’s impact by reaffirming the restrictive interpretation of “exclusive rights” articulated in Sybersound. The court reiterated that a co-owner’s transfer of exclusive rights is binding only on the transferring co-owner’s share and not on the remaining co-owners. The court then followed this correct principle with the incorrect conclusion that because Tresóna hadn’t obtained consent from the other co-owners, it lacked true “exclusive” rights and therefore lacked standing to sue a third-party infringer. By doubling down on Sybersound‘s restrictive logic, Tresóna further muddles an already perplexing state of affairs.

Perhaps the decision to sue a high school choir brought Tresóna some bad karma—but the ripple effects now complicate copyright enforcement for everyone else. What a mess.

Cutting Through the Weeds of Co-Owner Rights

What Does “Exclusive” Really Mean?

The meaning of “exclusivity” shouldn’t be so complicated. Each co-owner of a joint copyright owns an undivided share of the whole. If a co-owner assigns or licenses an exclusive interest in their proportional share of the work, the transferee acquires standing to bring infringement claims against third parties without joining the other co-owners. The right is exclusive in the sense that the assignee gains the sole ability to enforce the assignor’s interest against the world, except as to the other co-owners, who retain their independent rights.

The Unworkable Reality of a Unanimity Requirement

The “Flowers” case highlights the flaws in a unanimity-based approach. Tempo Music owns a fractional share of “When I Was Your Man,” acquired from co-author Philip Lawrence. Under the Ninth Circuit’s rule, Tempo would need to secure the participation or consent of co-writers Bruno Mars, Ari Levine, and Andrew Wyatt to proceed with its lawsuit against Miley Cyrus and the other defendants. This level of cooperation isn’t just burdensome—it’s often impossible. Co-owners may have conflicting interests, lack the resources to join a lawsuit, or simply be unwilling to participate. Maybe they’re on tour, off the grid, or in a coma. In such cases, requiring unanimity effectively leaves joint copyright owners without recourse against infringers.

Defendants Risk Undermining Their Own Rights

Ironically, the logic advanced in Cyrus’s motion could undermine some of the very defendants in the “Flowers” case. Music publishers and record companies frequently hold fractional shares of songs. If they were to sue third parties for infringing their own copyrighted works, the same procedural barriers could prevent them from enforcing their rights without unanimous agreement from their co-owners. Given this reality, it’s surprising that any of the defendants in the “Flowers” lawsuit are advancing this argument. Indeed, organizations like the National Music Publishers Association, Nashville Songwriters Association International, ASCAP, and BMI have long criticized the Ninth Circuit’s restrictive approach in cases like Sybersound and Tresóna, warning of its potential to hamper copyright enforcement.

The fact is that individual co-owners routinely bring copyright infringement cases without joining their fellow co-owners. Just this month, the Second Circuit decided a copyright infringement case brought by Structured Asset Sales (SAS) involving Ed Sheeran’s hit Thinking Out Loud. Like Tempo Music Investments, SAS is a firm that acquires royalty interests from copyright holders, securitizes them, and sells those securities to investors. SAS had standing to pursue its appeal even though it owned only a one-ninth interest in the royalties from Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get It On—and did so without involving the other co-owners of the song.

SAS is hardly alone. Sony Music Publishing—one of the defendants in the “Flowers” case that didn’t join Cyrus’s motion to dismiss—has previously argued in the Ninth Circuit that a joint owner of copyright is not required to join its co-owners in an infringement action, relying on Davis v. Blige. This inconsistency highlights the weaknesses—and potential risks—of the defendants’ current strategy.

The Bottom Line

A co-owner’s ability to sue third-party infringers isn’t just a procedural issue—it’s a cornerstone of effective copyright protection. It’s time for courts on the West Coast to cut through the weeds of confusion and consistently allow copyright holders to enforce their rights as Congress intended.

At least, that’s my take. What do you think of the Ninth Circuit’s approach? Let me know in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of Miley Cyrus’s motion to dismiss, which you’re welcome to read without anyone else’s consent.

View Fullscreen