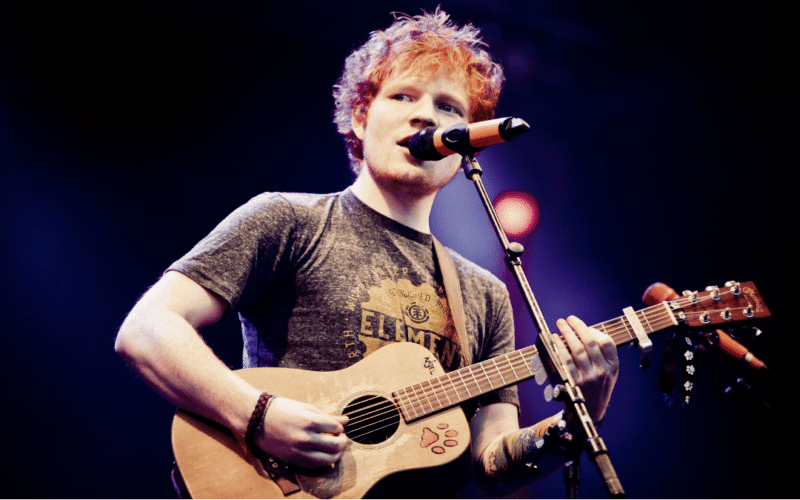

In a copyright battle over pop music’s building blocks, the Second Circuit delivers a win for Ed Sheeran—and for future creativity.

The Second Circuit has spoken: the I–iii–IV–V chord progression is officially unoriginal, commonplace, and free for all to use—whether you’re an eight-year-old plucking out “Puff the Magic Dragon” on a toy guitar or a redheaded rock star named Ed. In a decision issued Friday, the court ruled that Ed Sheeran’s 2014 song “Thinking Out Loud” didn’t infringe the copyright in “Let’s Get It On.” The court rebuffed an attempt by Structured Asset Sales (SAS)—a private equity-backed fund that owns an 11.11 percent interest in the royalties from Marvin Gaye’s classic track—to monopolize fundamental building blocks of music. As the three-judge panel succinctly put it: “Overprotecting such basic elements would threaten to stifle creativity and undermine the purpose of copyright law.”

The new ruling comes about a year and a half after a jury cleared Sheeran of similar copyright infringement claims in a case brought by the estate of Ed Townsend, co-writer of “Let’s Get It On.” The decision should, by all rights, put an end to speculators buying up portions of popular songs with the aim of profiting through copyright litigation—but it won’t.

The court’s full opinion runs 28 pages (read here), but here are my five key takeaways.

1. The Copyright Act of 1909 Limits Scope to the Deposit Copy

A key dispute in both the Structured Asset Sales and Townsend cases was whether the copyright in “Let’s Get It On” was defined by its written deposit copy or if additional elements from Marvin Gaye’s recorded version could also be considered in an infringement analysis. The “deposit copy rule” is a holdover from the 1909 Copyright Act, which still applies to works registered before 1978. Under this rule, copyright protection for older works is strictly limited to the sheet music filed with the Copyright Office, not what was captured in the studio recording.

The deposit copy rule is archaic, but per the Second Circuit, it’s the law. The court held that SAS couldn’t rely on elements found only in Gaye’s recording—like the song’s bass line—to argue infringement. Instead, only those musical elements explicitly included within the four corners of the sheet music, such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and lyrics, were relevant for evaluating the claim. This significantly narrowed the scope of what SAS could argue was protected, excluding any performance nuances or elements unique to Gaye’s recording. In short, if it wasn’t on the sheet music, it wasn’t part of the case.

2. Expert Testimony Can’t Infer Elements Beyond the Deposit Copy

SAS leaned heavily on testimony from its expert, John Covach, who “inferred” a bass line from the chord symbols in the “Let’s Get It On” sheet music, arguing that musicians would naturally interpret the chords to imply a specific bass line. The district court rejected this approach, noting that “[t]here is no bass line in the . . . Deposit Copy,” and emphasizing that “copyright law protects only that which is literally expressed, not that which might be inferred or possibly derived from what is expressed.”

The Second Circuit agreed with the lower court’s assessment, further underscoring the deposit copy’s critical role in defining the scope of copyright protection for works registered under the 1909 Act.

3. Common Musical “Building Blocks” Aren’t Protectable

A central aspect of the Second Circuit’s ruling focused on the chord progression and harmonic rhythm in “Let’s Get It On.” The song uses a simple four-chord progression, three of which are the basic I–IV–V chords. The panel held that this progression isn’t protectable on its own, reiterating that courts consistently view “the basic chord progressions so ubiquitous in popular music as unoriginal and, thus, unprotectable.” Similarly, the court found that common harmonic rhythms, like the syncopated “anticipation” technique used in the song, are fundamental building blocks of music and aren’t entitled to copyright protection.

In a particularly notable section of the opinion—likely to be cited early and often by lawyers defending the more than 150 artists, songwriters, and record companies sued in the massive reggaetón lawsuit that I covered last year—the court underscored that rhythm alone isn’t copyrightable. The court observed that “originality of rhythm is a rarity, if not an impossibility,” reinforcing that fundamental musical elements remain free for all to use, thereby preserving the creative space for future compositions.

4. Selection and Arrangement Requires More than Simple Combinations of Common Elements

SAS argued that even if the chord progression and syncopated rhythm in “Let’s Get It On” are individually unprotectable, the “selection and arrangement” of these two elements was sufficiently original to warrant protection. However, Sheeran’s expert, Lawrence Ferrara, demonstrated that the same combination of elements appeared in several earlier songs, including “Georgy Girl” and “Since I Lost My Baby.” SAS’s expert countered by claiming these combinations weren’t widely recognized by the public, but the court dismissed this argument. It emphasized that an original “selection and arrangement” of unprotectable elements hinges not on whether a particular combination is “well-known,” but rather on (i) the total number of available options, (ii) external factors that limit the viability of certain options or render them non-creative, and (iii) prior uses that render certain selections “garden variety.”

While the court didn’t rule out the possibility that the selection and arrangement of just two elements could be protectable, it held that SAS’s particular selection-and-arrangement claim failed because “it risks granting a monopoly over a combination of two fundamental musical building blocks. The four-chord progression at issue—ubiquitous in pop music—even coupled with a syncopated harmonic rhythm, is too well-explored to meet the originality threshold that copyright law demands.”

5. No Substantial Similarity Based on the “Total Concept and Feel”

The final takeaway from the court’s decision is its determination that no reasonable jury could find “Thinking Out Loud” and “Let’s Get It On” substantially similar as a whole. The court emphasized that, beyond the alleged similarities in chord progression and harmonic rhythm, the two songs differ in essential aspects, such as melody and lyrics. Without substantial similarity in these core components, the songs couldn’t be considered infringing, even though they may share a similar sound and feel.

While plaintiffs can allege infringement based on shared musical elements, these elements alone are insufficient without broader similarities in the “heart” of the works. In this case, distinct differences in melody, lyrics, and overall structure between Sheeran’s and Gaye’s songs effectively closed the door on a viable infringement claim.

The Bottom Line

The Second Circuit’s decision in Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran serves as a comprehensive reminder of the limits of copyright protection in music. By emphasizing the narrow scope of the deposit copy, reaffirming the “building blocks” doctrine, and requiring a high threshold of originality for selection and arrangement claims, the Second Circuit has set a high bar for future copyright litigation in the music industry.

For songwriters, composers, and copyright holders, the takeaways are clear: relying on common musical elements, even when creatively arranged, may not suffice to claim copyright infringement. Courts will likely remain vigilant against attempts to monopolize fundamental musical elements, keeping the creative field open for artists across all genres.

As always, I’d love to hear what you think. Drop me a note in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the Second Circuit’s opinion in Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran, the perfect holiday gift for that one friend who insists they invented the I–iii–IV–V progression.

View Fullscreen

3 comments

On the subject of your second point, I thought the argument made by Covach was quite self-defeating. If the implied bassline is so obvious that any competent musician would automatically play it, how does that not walk right into scene a faire or merger territory?

How does this result square with the Blurred Lines case?

With the passage of time (and cases like Skidmore, Dark Horse and now Sheeran, Blurred Lines is looking more an more like an outlier.