Photographer Jeff Sedlik and tattoo artist Kat Von D each claim that the Supreme Court’s Warhol decision entitles them to summary judgment in their long-running copyright dispute.

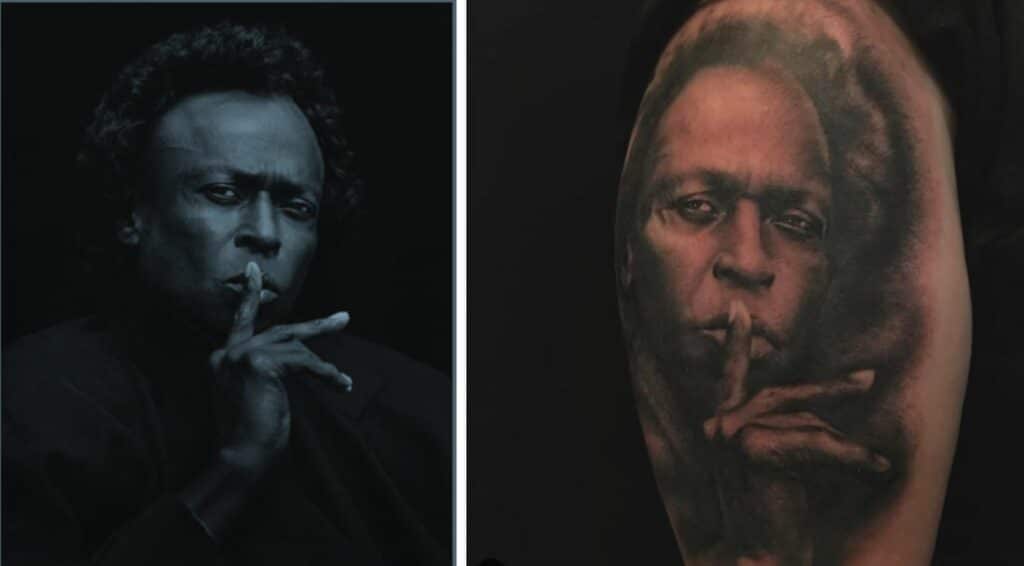

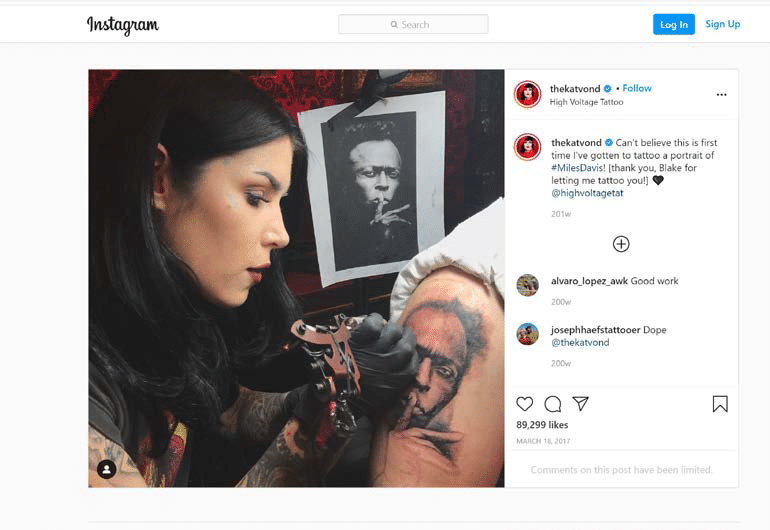

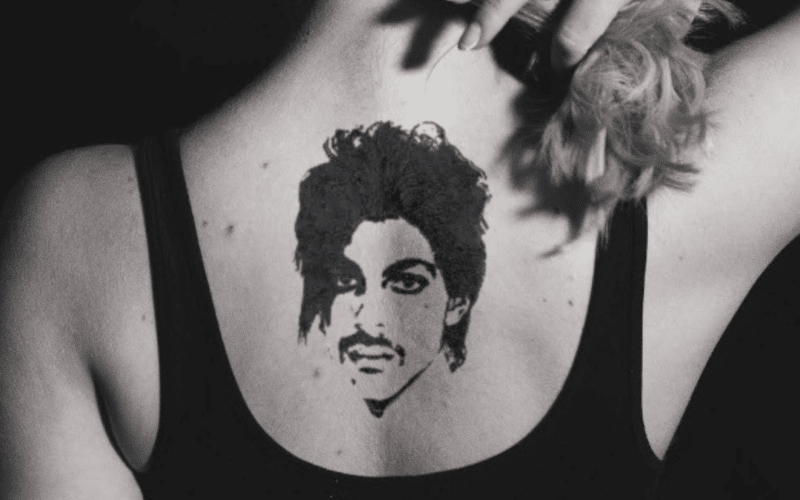

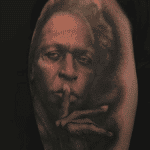

Fifteen minutes of fame, meet permanent ink. A Los Angeles federal judge is set to decide the impact of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith on a first-of-its-kind copyright infringement lawsuit involving celebrity tattoo artist Katherine Von Drachenberg (aka Kat Von D). Photographer Jeff Sedlik filed the lawsuit in February 2021, claiming that Von D infringed the copyright in his photo of Miles Davis by tattooing a reproduction of the image on her friend Blake Farmer’s arm and by displaying images of the tattoo on her social media accounts.

A little over a year ago, District Court Judge Dale S. Fischer denied both parties’ motions for summary judgment, finding triable issues of substantial similarity and fair use. While the court didn’t mention the yet-to-be-argued Warhol v. Goldsmith in its 30-page ruling, I speculated at the time that Judge Fischer may have purposefully avoided making legal rulings that could later be subject to reevaluation in light of the eventual Supreme Court decision. Indeed, last November, the court vacated the trial date and stayed Sedlik’s lawsuit pending the outcome of Warhol.

The Supreme Court issued its ruling in Warhol on May 18. Judge Fischer quickly lifted the stay on May 26 and ordered the parties to meet and confer concerning the impact of the new decision. Following their discussions, the judge requested that the parties brief motions for reconsideration, which they filed last week. Interestingly, both sides are claiming that Warhol entitles them to victory as a matter of law.

UPDATE—January 23, 2024: The Kat Von D tattoo trial has officially begun. Check out my full breakdown here.

Kat Von D’s Motion

In its previous ruling on the parties’ motions for summary judgment, the court found triable issues of fact with respect to both the first fair use factor (purpose and character of the use) and the fourth (effect of the use upon the potential market).

Among other things, the court held that there was a factual dispute as to whether or not defendants’ purpose in using Sedlik’s image of Miles Davis was “commercial.” Neither Kat Von D nor her company had charged Blake Farmer a fee for inking the tattoo on his arm, but Sedlik argued that defendants received an indirect economic benefit by posting photos of the tattoos on their social media platforms. The court ultimately found that these were factual disputes that would need to be decided by a jury.

In their motion for reconsideration (read here), defendants contend that the court erred by not considering each of the challenged uses separately, as counseled by Warhol: “Sedlik alleges that there were multiple separate infringements of his photograph, by the Tattoo itself, by social media posts depicting photographs of Kat Von D in the process of creating the Tattoo, and by social media posts of the Tattoo in various stages of completion . . . Under the new rule set forth in Warhol, each of those challenged uses must be analyzed separately and assessed on their own terms.”

Focusing on the tattoo itself, defendants argue that “[t]he specific challenged use—a non-commercial tattoo hand-inked on the arm of Kat Von D’s friend—is nothing like the copyrighted use, a photograph licensed to be used in a magazine article about Miles Davis.” (Defendants aren’t seeking reconsideration of the court’s summary judgment order as it applies to Kat Von D’s social media posts, and ask for the previously-ordered jury trial on that issue.)

Defendants ask the court to re-weigh the four fair use factors in light of Warhol, concluding that, “Of the important factors, all weigh in favor of fair use except the second part of the fourth factor (the market for future uses) in connection with which there is a dispute of fact.”

Jeff Sedlik’s Motion

In his motion for reconsideration (read here), plaintiff Jeff Sedlik largely focuses on the fourth fair use factor (effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work). This factor received a mixed ruling in the court’s previous order, with Judge Fischer concluding that there is “no evidence that the Tattoo is a substitute for the primary market for the Portrait,” but that the facts were disputed as to whether there was a “market for future use of the Portrait in tattoos.”

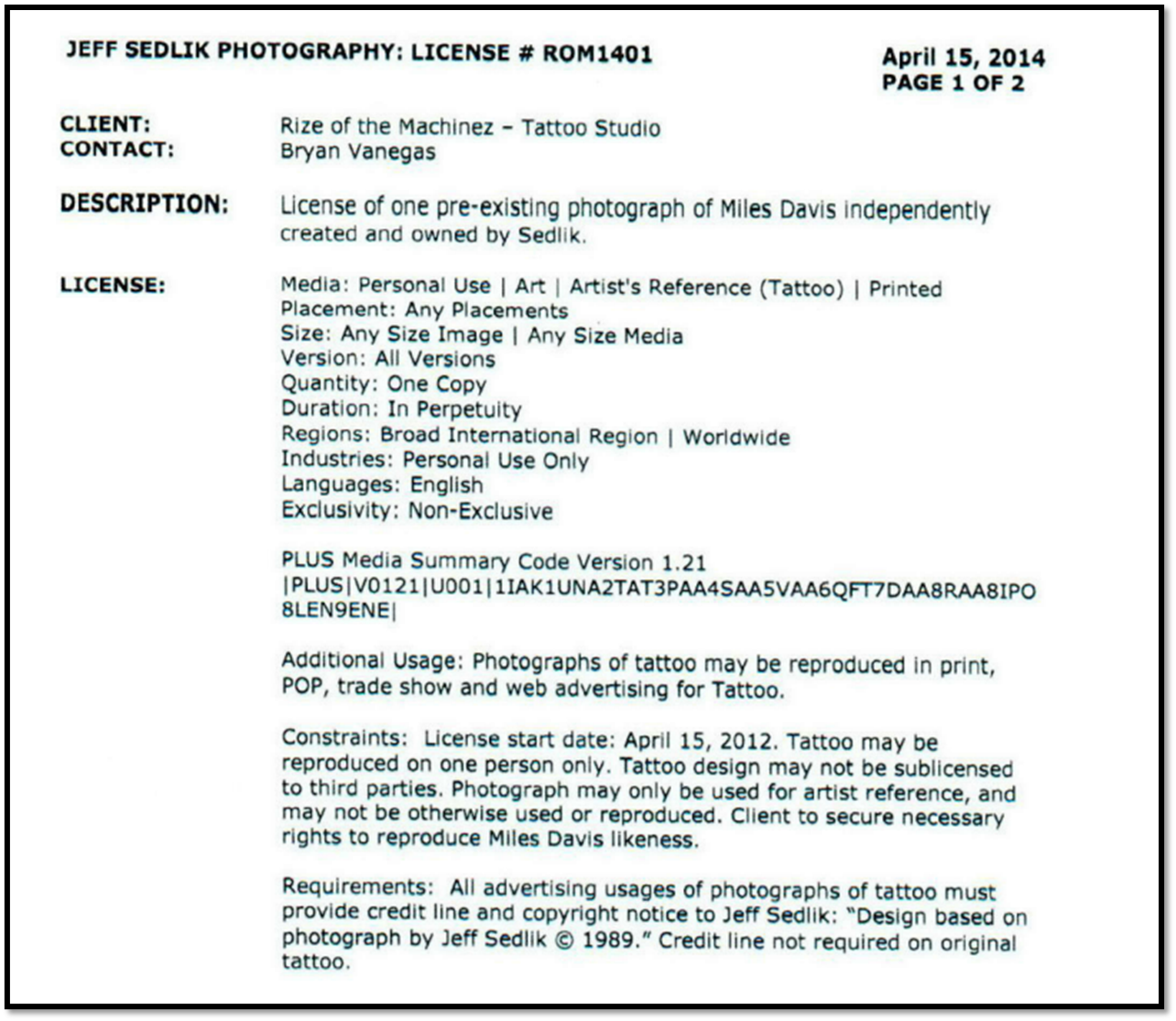

Seizing on the new Supreme Court decision, Sedlik argues that “Warhol clarified that photographers routinely license their creative works to serve as reference for other artists, and that such artists’ reference licenses are how photographers make their living.” To underscore this point, Sedlik offers evidence that he previously licensed the use of the same Miles Davis photo to another tattoo artist for use as a reference image.

Sedlik also argues that Warhol rejected the notion that a work is “transformative” under the first fair use factor merely by adding new expression to the original work, and that the new use must instead have a further purpose or character. He contends that because he’s in the business of licensing his photos as reference images and for the creation of derivative works, the parties’ uses “have the same purpose—the display of a portrait of Miles Davis. Just because one is on canvas and one is on skin does not change the purpose.”

A Few Thoughts

In issuing a stay last year, Judge Fischer was no doubt hoping that Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith would provide some much-needed clarity on copyright fair use. But as I noted in my breakdown of the decision, that didn’t happen. The fact that Jeff Sedlik and Kat Von D are both claiming victory post-Warhol speaks to the still-confused state of the law.

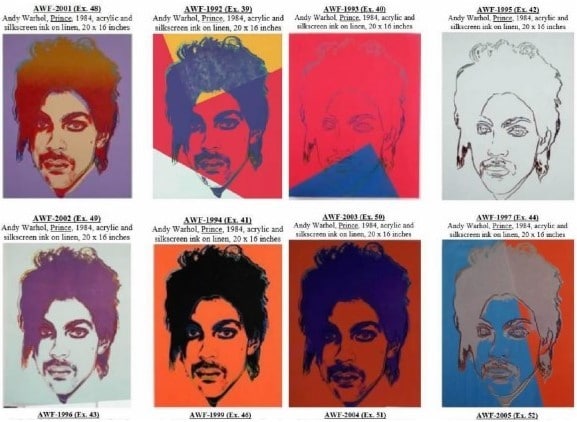

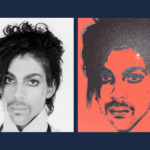

It also shows that Warhol offers a little something for everyone. The requirement for each particular use to be considered on its own seemingly allows Judge Fischer to find that the tattoo itself is fair use even if the social media posts depicting it may not be. Recall that the Supreme Court majority limited its own fair use analysis to the licensing of Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince to Condé Nast in 2016. The Court expressed “no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of any of the original Prince Series works.”

Unfortunately, the particular facts of Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg also expose the shortcomings in the Supreme Court’s Warhol approach. There, the Court declined to find that Andy Warhol’s original creation was infringing, deciding only that the subsequent licensing by his foundation weighed against fair use. Here, Kat Von D is asking Judge Fischer to rule that her original act of inking qualifies as fair use, while leaving it up to a jury to determine the fate of images of the resulting tattoo.

It’s all well and good for lawyers, judges, and jurors to debate whether one particular use is fair and another isn’t, but where exactly does this leave poor Blake Farmer? He’s now walking around with a law school hypothetical permanently attached to his right arm. License or no license, for better or worse, once that tattoo was affixed to his body, it became part of his persona. As a result, any photograph of Farmer’s arm will arguably infringe Jeff Sedlik’s photograph. Is Farmer allowed to post photos of the tattoo on his Instagram account? Is he allowed to accept a role in a commercial advertisement if the tattoo is visible? Putting aside all of the bodily autonomy and privacy issues I’ve written about in my prior tattoo-related posts, the problem with considering fair use on a “use by use” basis is that it never ends.

The Bottom Line

A hearing on the parties’ dueling motions for reconsideration in Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg is currently scheduled for September 18, 2023. I’ll keep you posted about the outcome. In the meantime, Blake Farmer may want to consider investing in long sleeve shirts.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Drop me a note on social media @copyrightlately or use the comments box below.

Defendants’ Motion for Reconsideration:

View FullscreenPlaintiff’s Motion for Reconsideration:

View Fullscreen

1 comment

The current standard of review, on a case-by-case basis, has a very Jacobellis v. Ohio feel to it, doesn’t it? I keep thinking that maybe they can come up with something like 70% of pixels within two tone scales of the original objective test, but I just don’t see that as workable. That tension between encouraging creativity and supporting ownership rights has always been a challenge, and now with AI added into the mix…. Fun times. Thanks for another excellent article.