As screenwriters and studios negotiate AI’s role in the entertainment industry, it’s important to be mindful of some core copyright protection principles.

In a decision that surprised exactly no one, D.C. District Court Judge Beryl A. Howell ruled last Friday that the Register of Copyrights did not act “arbitrarily or capriciously” in denying a copyright registration to Dr. Stephen Thaler for artwork generated entirely by artificial intelligence. “Human authorship,” Judge Howell wrote, “is a bedrock requirement of copyright,” which has never stretched so far as to protect works generated “absent any guiding human hand.”

The Copyright Office’s position on this subject has always been crystal clear: works created by “non-humans”—whether they be AI, animals, or divine beings—aren’t eligible for copyright protection. But while human involvement is essential to copyright protection, the mere presence of a human author doesn’t provide some secret backdoor way of making AI-generated content copyrightable. Repeat after me: content created by human beings can be protected by copyright. Content generated by AI can’t.

This distinction may have have been lost on some observers in the days following the Thaler decision—especially against the backdrop of the ongoing writers’ strike, which is about to enter its fifth month. An article in the Hollywood Reporter earlier this week suggested that there’s finally been some movement between the parties with respect to generative AI, as studios recognize that copyright protection in AI-generated scripts is only possible for those works if they’re revised by human writers. The article quoted an unnamed source close to the AMPTP as saying,“If a human touches material created by generative AI, then the typical copyright protections will kick in.”

Not exactly. This may be true, but only if we recognize that the “typical copyright protections” don’t include AI-generated content which makes up an appreciable part of a work. If content contributed by AI is more than de minimis and would qualify for copyright protection had it been created by a human author, that content needs to be disclosed to the Copyright Office and will be excluded from protection.

Welcome to the world of “unclaimable material,” a strange land where material that could be protected by copyright isn’t protected by copyright.

What Is Unclaimable Material?

For purposes of a copyright registration, “unclaimable material” has historically included four types of material:

- Previously published material.

- Previously registered material.

- Material that is in the public domain.

- Copyrightable material that is owned by a third party.

In March of this year, the Copyright Office issued a new policy statement that essentially added a fifth category of unclaimable material to the list: AI-generated content. If AI technology determines the expressive elements of its output, the generated material is not considered to be the product of human authorship, and therefore not protected by copyright.

What’s important to remember is that if a work contains an “appreciable amount” of unclaimable material, that material needs to be disclosed and disclaimed in a copyright registration application. The disclaimed material is then excluded from the claim of copyright.

While Dr. Thaler attempted to register a copyright claim in material created entirely by AI, it’s more often the case that a work containing AI-generated material will also contain sufficient human authorship to support a copyright claim. For example, a human author may select or arrange AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way. Or an author may modify material originally generated by AI to such a degree that those modifications meet the standard for copyright protection. In these cases, copyright will protect the human-authored aspects of the work. Importantly, however, there will still be no copyright protection in the AI-generated material itself.

Think of human modifications to AI as a quasi-derivative work—the copyright in a derivative work only extends to the material contributed by the author of that work, as opposed to the underlying material. “The copyright in such [derivative] work is independent of, and does not affect or enlarge the scope, duration, ownership, or subsistence of, any copyright protection in the preexisting material.”

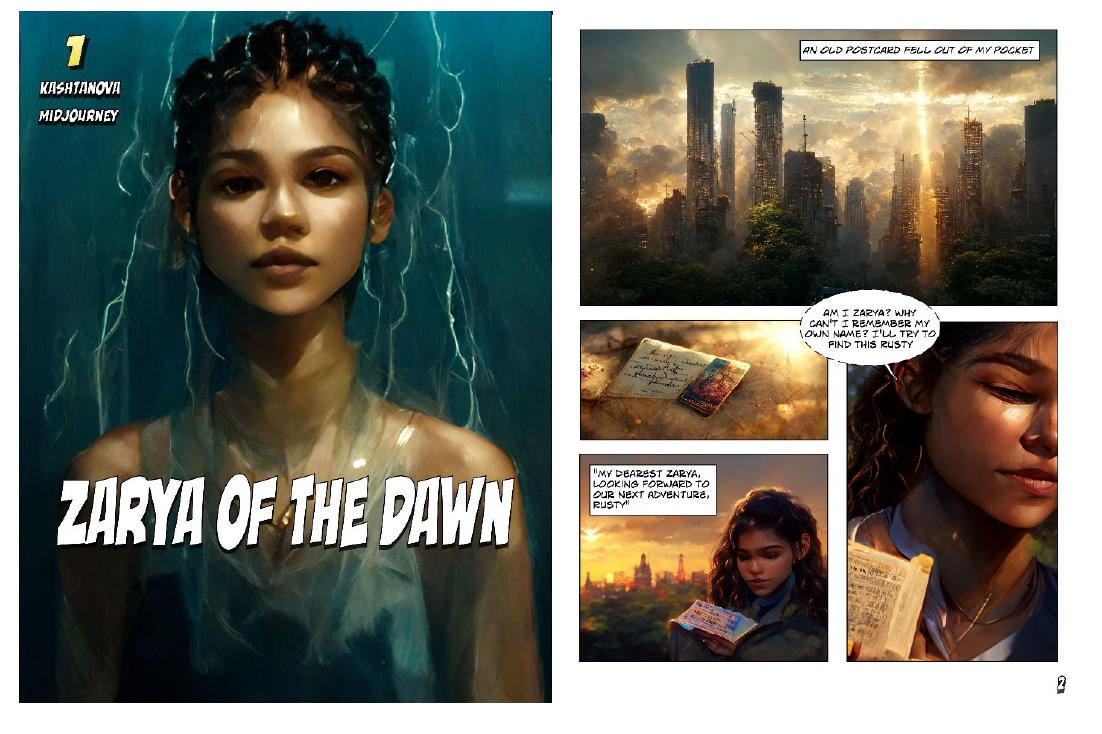

An example of this rule in action is demonstrated by the recent Copyright Office registration decision involving Kristina Kashtanova’s Zarya of the Dawn. The Office concluded that the original text and compilation of the elements in Kashtanova’s comic book were sufficient to support a claim of copyright. However, it canceled their original registration for failing to disclose that the comic’s illustrations were generated by AI. A newly-issued registration clarifies that copyright protection in Zarya does not extend to any of the individual images themselves because they lack the requisite level of human authorship.

“Appreciable” vs. “De Minimis” Amounts of AI-Generated Content

While AI-generated material will never itself be protected by copyright, it only needs to be disclosed and excluded from a copyright application if a work contains an appreciable amount of AI-generated content. So-called “de minimis“ uses of AI don’t need to be disclosed. Determining where and how to draw the line between appreciable and de minimis requires conducting a counterfactual exercise: Would the AI-generated material be copyrightable if it had been created by a human author? If the answer is yes, the Copyright Office considers it appreciable and disclosure is required.

Many times, the answer will be no. If a work contains material that is uncopyrightable, such as facts, short phrases or mere ideas, there is no need to exclude that material from a claim of copyright—regardless of whether it was generated by a human or by AI. So, for example, if an author uses AI for brainstorming and ideation (offering potential character names, ideas for plot points, etc.), but no appreciable amount of AI-generated material is contained in the final script submitted for registration, there’s no need to disclose or exclude the AI. The same is true if AI is used for technical tasks—blurring out license plate numbers from reality show footage or performing color corrections. These tasks, if performed by humans, wouldn’t be considered copyrightable contributions, so they don’t need to be excluded if performed by AI.

On the other hand, if a director uses AI to produce some of the special effects for a movie, the AI-generated content would need to be disclaimed, because they would be considered a copyrightable contribution to the motion picture if the material had been created by a human author. The same is true if a writer were to use ChatGPT to generate a rough draft of a script, which he then lightly polishes and punches up. The resulting screenplay is eligible for copyright protection, but so long as the finished product still retains underlying AI-generated material that would also be considered copyrightable, that material needs to be disclosed and is excluded from the claim. The mere presence of a “human touch” doesn’t confer copyright protection on the AI-generated portions.

What Happens if You Don’t Disclose Unclaimable Material?

The Copyright Office’s disclosure requirements aren’t onerous, and disclaimers of unclaimed material can be quite general. Don’t worry about providing a detailed spreadsheet of every use of AI technologies in the creation of your work. It’s typically enough to include a simple statement in the excluded material section of the copyright application to the effect that “some text was generated by AI.” If the Copyright Office has more specific questions, they’ll ask.

Occasionally, the Register of Copyrights is asked to provide advice to courts on whether the Register would have refused registration had the Copyright Office known of alleged inaccuracies in a copyright application. For example, just this week, the Copyright Office concluded that a tattoo design affixed to LeBron James’ chest was entitled to registration even though it’s based on a modified version of the Venetian Resort logo. The Office noted that, had a registration specialist known that the Lion tattoo design contained an appreciable amount of material owned by a third party, the specialist would have asked the artist to disclose and exclude that material from his claim.

You may be asking yourself, how would anyone know whether or not you used AI to generate dialogue for your screenplay? Unlike pre-existing works in the public domain, it’s nearly impossible to accurately prove that a work has been created by AI—at least for now. In the future, there may well be tools that can determine whether a particular work is comprised of an appreciable amount of AI-generated material. By not disclosing, you run the risk of having your entire copyright registration invalidated.

The Bottom Line

Contrary to popular belief, I don’t think it’s realistic to think that studios will replace screenwriters with movie and television scripts churned out by ChatGPT. Strike or no strike, no one wants to spend millions of dollars to produce and market a work that they can’t fully protect. And merely having a human writer give minor touch ups to an AI-generated screenplay won’t provide the desired copyright protection either.

The greater the amount of AI material that finds its way into a final product, the less protection that output will receive. Therefore, it seems much more likely that studios are going to want to minimize the amount of off-the-shelf AI incorporated into their creative output, at least insofar as that material would be entitled to copyright protection had it not been created by AI. That will require writers who identify as human.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Let me know in the comments below or @copyrightlately on whatever social media app you aren’t boycotting this week.

13 comments

Here’s the relevant question, I think: does Hollywood already invest in films where some of the material involved cannot be protected? As you note, there are other categories of unclaimable material, like that in the public domain. And indeed, big entertainment productions based on public domain material are produced all the time, with large budgets: anything based on the works of Hans Christian Andersen (the Little Mermaid) or L. Frank Baum (the Wizard of Oz), or Homer (Troy) and I’m sure many other examples besides. That material can’t be protected, but it’s mixed in with other material that can be. For instance, the original Judy Garland Wizard of Oz film has changes and additions to the material that are still under copyright. The new adaptations now underway can use anything in the Baum novels but not in more recent adaptations, and then they too are “mixture of claimable and unclaimable,” just like the Judy Garland film is now.

Are these exceptions, because the properties involved are so well-known and beloved, unlike a brand-new AI generated script? I’m not so sure. Let’s imagine an author went back to an old public domain fairy tale story and found a lesser-known tale… the Goat Girl, or Hans the Mermaid’s Son, or something like that. The author writes a novel, or a screenplay, using the characters and plot, just as for the Little Mermaid. Indeed, this is a common tactic for lots of authors these days, mining mythology and public domain material to reboot. The novel or screenplay is thus a mixture of claimable and unclaimable. Is a studio likely to option it? Well, if they think it’ll make money, why not? It’s not quite as great a deal, since someone else could always make a Goat Girl movie, TV show or film — they can’t have exclusivity on the character, but the details of how the story was revised, all the new human elements, are copyrighted.

This situation is actually a little better for the AI-produced script that’s modified extensively by a human, because the unclaimable AI script never has to be published. The copyright office doesn’t care about which sentences are AI-generated or human-written. The studio can lock it in a vault and never let anyone see it, and not have to worry about someone making derivative works off the unclaimable original. Depending on the generative AI method used (for instance if the AI didn’t generate the *whole* script, just chunks) the unclaimable chunks might not even constitute enough to steal from.

Hi Holly,

Creating a new film based on a book in the public domain is a good analogy for a lot of the potential use cases, but there are other conceivable scenarios in which a studio may think twice about using AI. For example, lets say that an AI tool were used create a new, fully delineated fictional character. Theoretically, at least, others could use that character in their own new works. Of course, they’d need to have visibility into which aspects of the project were generated by AI and which weren’t, which could be challenging as a practical matter, at least given that there’s really no accurate way to currently determine what’s been created by AI and what hasn’t. In the future, this could change. There’s really no telling how the technology and Copyright Office disclosure rules may evolve.

Thanks for the reply, Aaron. It’s definitely a rapidly evolving area. Associate Register Robert Kasunic said in a session on the new guidance that “high-level storyline” is likely to constitute an idea, not an expression, so I suppose the “fully delineated fictional character” might fall on either side of the idea-expression divide depending on how the ideas are set down! (Has anyone tried to copyright a plot outline or a written description of a character, as opposed to the final work the character appears in?) Fascinating stuff, thank you.

From the studios’ viewpoint, I have been thinking about the type of case Aaron posits. For example, it seems to me that an “idea”-level prompt could be used to generate a fantasy world with a few delineated characters and some other specific elements. It could generated by AI as a first draft treatment or screenplay. In litigation it might be possible, or might even be easy, to distinguish that first draft from subsequent ones. Computers are pretty good, aren’t they, at tracking dates of file creation? Now a potential user might not be willing to take the chance and use the creation without permission. But who knows how information travels these days? And in a negotiation to acquire rights, during a chain of title discussion, the potential buyer could discover the “truth” about the first draft. No?

I could definitely be wrong, but I think this decision only covers content that is autonomously generated by AI. A human leveraging ChatGPT does not meet that standard. I’m not aware of any autonomous AI agents out there creating movie scripts, so for now, I think most actors, writers, etc are safe.

what if I use something like Controlnet? How would you separate the human-made part from the AI-Generated parts when you’re trying reproducing AI-Generated parts of the work?

If you’ve uploaded reference pictures or sketches, those are protectable, but likely anything that is generated based on the assigned wouldn’t be.

But isn’t silhouettes protected? Wouldn’t what’s generated contain the silhouette of your expression?

You can’t really separate the AI generated portions for the human made.

I think we’re all still waiting on the USCO to give an answer regarding Kris Kashtanova’s image they submitted for registration a while back, a piece that I think used ControlNet to generate a fully rendered image from their drawing.

I wonder if they’re waiting on the Class Action lawsuit results before deciding? There’s another case management hearing scheduled for tomorrow, maybe the judge will finally give an official order for at least some parts of the claim.

Aaron, thanks for your very useful article and especially for tying in the discussion to the WGA strike. I think there’s been too little of that connection in the media coverage of the strike, and I presume in the strike negotiations themselves. That’s partly because of the ” sexiness” of “everything AI” these days. It makes a headline-grabbing rallying cry. But as your analysis shows, this is not a sensible “us vs. them” strike matter. It does raise serious questions and understandable concerns for both sides in the negotiations. But both have a stake in the protection of the materials that go into audiovisual works. Writers may want to reduce use of AI as potential replacements, but so do studios want human-created copyrightable material for their dollars. This is one to noodle on together and not necessarily in the heat of difficult collective bargaining.

Ah, that explanation of unclaimable material answers a few questions I had! Thanks, clear and cogent exploration of the issues.

It’s not storyline and plots I think will be the problem, but the use of tools like Sora, or the way that pixar uses AI to help add realism to their animated characters or light the scenese that I suspect will be most impacted and difficult to assess in the context of the copyright office guidance.