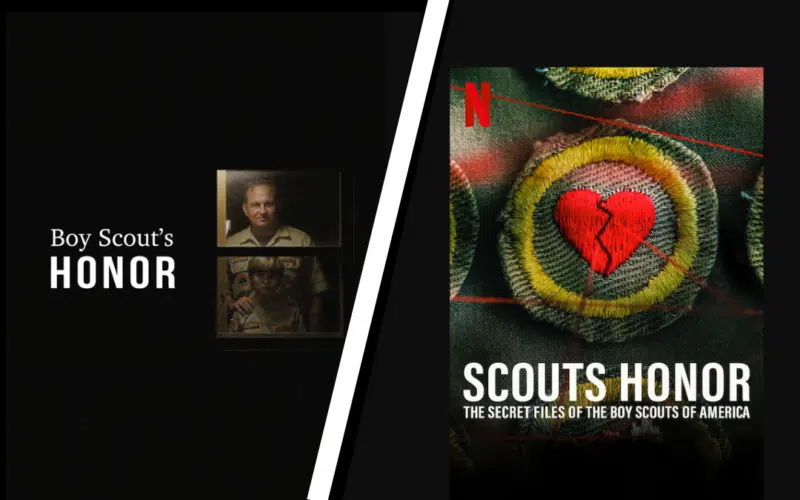

Two documentaries, one Boy Scouts scandal—a trial lawyer claims Netflix copied his film, but the legal trail ahead looks rocky.

New Jersey trial attorney Bruce Nagel is no stranger to taking on big institutions. He’s battled oil companies, insurance giants, and even the Boy Scouts of America—a fight that inspired him to produce Boy Scout’s Honor, a documentary exposing the harrowing stories of child abuse within the scouting organization. Now, that documentary is at the center of a copyright infringement showdown with Netflix, and this time, Nagel’s not just the lawyer—he’s also the plaintiff.

The lawsuit, filed last week by Nagel’s production company, B. Nagel Films, claims that Netflix’s 2023 documentary, Scouts Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America, is a near replica of his own film. (Read Nagel’s complaint here.) Both documentaries tackle the same explosive subject matter: decades of child sexual abuse within the Boy Scouts of America and the organization’s alleged cover-ups. But Nagel contends that Netflix’s film goes beyond merely sharing the same basic idea, alleging that it also appropriates his documentary’s stylistic choices and narrative elements, resulting in a “wholesale copying” of Nagel’s film.

Nagel is about to find out that earning a merit badge in copyright law can be tougher than climbing Eagle Rock with a full pack, and obstacles like the idea-expression dichotomy, scènes à faire, and the merger doctrine promise to make this lawsuit anything but a campfire sing-along.

B. Nagel Films v. Netflix – Claimed Similarities

Nagel’s complaint argues that Scout’s Honor closely mirrors his film, which hit streaming platforms in 2022, nine months before the Netflix offering. Both documentaries cover a disturbing subject that demands sensitivity—and, as it turns out, a lot of overlap.

Similar Titles

The films’ titles—Boy Scout’s Honor and Scouts Honor—are undoubtedly close. But copyright doesn’t protect titles or short phrases, so this similarity won’t help Nagel much. Besides, was he really expecting Netflix to call this thing The Joy of Scouting?

Theme and Structure

The complaint alleges that both films use interviews, historical documents, music, and stock footage to create a jarring contrast between scouting’s wholesome image and the darkness beneath. In short, Nagel seems to be accusing Netflix of making a documentary that looks suspiciously like. . . a documentary.

Visuals

Nagel claims that Netflix borrowed heavily from his film’s visual style, especially shots of campfires, tents, and other iconic scouting imagery. The complaint doesn’t contain any images, but I was able to pull a few screen grabs from the documentaries at issue. Really, though, this is Documentary 101—juxtaposing disparate elements to create tension or challenge the audience’s expectations.

Expert Interviews

The complaint calls out Netflix’s use of lighting and framing techniques, specifically a shadowy effect known as “chiaroscuro” to emphasize skin textures, with interview subjects seated in an office setting with a lamp partially visible in the background. While dramatic lighting in interviews can certainly be striking, it’s about as standard as a pinewood derby at a scout jamboree. Shots like this are documentary staples, and frankly, these just aren’t similar.

Another alleged similarity involves scenes in which experts discuss the mountain of abuse files maintained by the Boy Scouts of America. According to Nagel, Netflix’s shots of slightly blurred hands flipping through stacks of in-focus documents were lifted straight from his film. I pulled the frames at the time stamps referenced in the complaint, and the expression looks totally different.

Victims Describe Vivid Sexual Abuse

In both films, sex abuse victims describe a revolting memory in which their nude abuser wrapped his legs around the victim’s head, while unnerving atmospheric music plays in the background. Horrific, yes. Protectable, no.

Closing Scenes

Finally, both films close with an epilogue about the Boy Scouts of America bankruptcy settlement trust and the lingering uncertainty it leaves for survivors. White letters appear over a black screen as dramatic music swells in the background. By this point in the complaint, you just might be convinced that Boy Scout’s Honor and Scouts Honor are the only two documentaries Nagel has ever watched.

The Limits of Copyright in Documentaries

Though Nagel is a well-known and accomplished trial attorney, getting this case past a motion to dismiss will require navigating a copyright landscape shaped by doctrines like the idea-expression dichotomy, scènes à faire, and the merger doctrine—principles that often narrow the scope of protection for works grounded in real-world events and issues.

The Idea-Expression Dichotomy: Facts Aren’t Protectable

As I discussed last week in connection with the new copyright infringement lawsuit filed by the author of a Fleetwood Mac memoir and the folks behind Stereophonic, copyright law protects the way an author expresses facts, but not the facts and ideas themselves. This distinction is especially relevant in documentaries. It’s why, for example, we can have multiple takes on the Fyre Festival fiasco, each diving into that same flaming dumpster of a music festival without stepping on each other’s toes—though I’m sure Billy McFarland would find a way to charge extra for that.

In Boy Scout’s Honor, the documentary is based on real-life accounts of abuse within the Boy Scouts of America and the organization’s alleged cover-ups—public domain facts that are inherently unprotectable. So while both documentaries feature interview subjects discussing the BSA’s abuse records (known as the “perversion files”), these are true facts that don’t fall under copyright’s tent. Similarly, Nagel can’t lay claim to the harrowing stories of abuse recounted by survivors—because some things aren’t meant to be owned.

While copyright can protect Nagel’s “selection, coordination, or arrangement” of facts in some cases, organizing interviews and historical documents chronologically is par for the course in documentaries. Even if Scouts Honor follows a similar structure, it won’t infringe Nagel’s copyright if it simply reorders or presents these public domain facts in a similar, albeit formulaic, manner.

Scènes à Faire: Unprotectable Stock Elements

Elements that naturally flow from a given subject matter aren’t just unoriginal; they’re practically inevitable to a treatment of that subject. That’s why copyright law considers these elements unprotectable under the doctrine of scènes à faire doctrine—they’re as predictable as mosquito bites at summer camp.

Bolton-Curley v. Scripps Networks

Take the recent Bolton-Curley v. Scripps Networks case decided just two months ago. The plaintiff claimed that Scripps’ documentary, Xernona Clayton: Life in Black and White, was substantially similar to her own film about the same civil rights activist. She pointed to elements like “identical interviews,” a chronological structure, voiceover narration paired with photos and video clips, and similar camera angles. The court found that these elements are just standard fare in documentaries that recount a person’s life story, deeming them “unprotectable and not copyrightable.”

Monbo v. Nathan

Similarly, in Monbo v. Nathan, the plaintiffs alleged that a documentary on Baltimore’s “12 O’Clock Boyz”—a local dirt-bike subculture—had borrowed too much from their earlier films on the same subject. The court concluded that the similarities—showcasing the streets of Baltimore, filming riders and stunts, and using techniques like news clips, slow-motion shots, and transitions between riding scenes and interviews—were all stock components of the genre. Simply put, the plaintiffs did “not have the exclusive right to make docu-fiction about dirt-bike riders, as methods of storytelling are not protectable.”

In Boy Scout’s Honor, Nagel claims that Netflix copied stock footage of campfires and scouting activities, as well as specific lighting techniques for interviews. While these choices may be stylistic, they’re common tools for setting mood and tone in documentaries—especially ones that deal with somber topics. Interviews with survivors, discussions about internal abuse files, and the depiction of scouting history are more than just common—they’re practically required.

The Merger Doctrine: Expression and Idea Become One

The merger doctrine presents yet another potential hurdle for Nagel. Where few options exist to express an idea, that expression may not be copyrightable because it has essentially “merged” with the idea itself. For example, if the only effective way for a documentary to depict the contrast between the Boy Scouts’ wholesome image and the grim reality of abuse is through visuals like campfires, tents, or somber music, those expressive elements won’t be protected. Nagel might hold a “thin” copyright in a particular sequence of images, but only to prevent nearly identical copying.

Take Zella v. E.W. Scripps Co., where the court observed that “there are only a finite number of ways to express the idea of a talk/cooking show with celebrities.” While the two shows in question bore some resemblance, the court pointed out that “so does every talk show to some extent”—a gentle reminder that certain elements just come with the territory.

The Bottom Line

For Nagel to succeed, he’ll need to demonstrate that Scouts Honor did more than just use stock conventions—it must have actually copied original, expressive elements from Boy Scout’s Honor. That won’t be easy, as documentaries based on real-life events often lean on familiar techniques that are typically unprotectable. With courts historically siding with defendants in similar cases, Nagel faces a steep, uphill climb to prove that Netflix’s documentary crossed the line from common tropes into copyright infringement.

But that’s just my take. I’d love to hear yours—drop me a comment below or on social media at @copyrightlately. In the meantime, here’s a copy of Nagel’s complaint to read by the campfire.

View Fullscreen