In a first-of-its-kind ruling, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has revived choreographer Kyle Hanagami’s copyright lawsuit against Fortnite’s Epic Games.

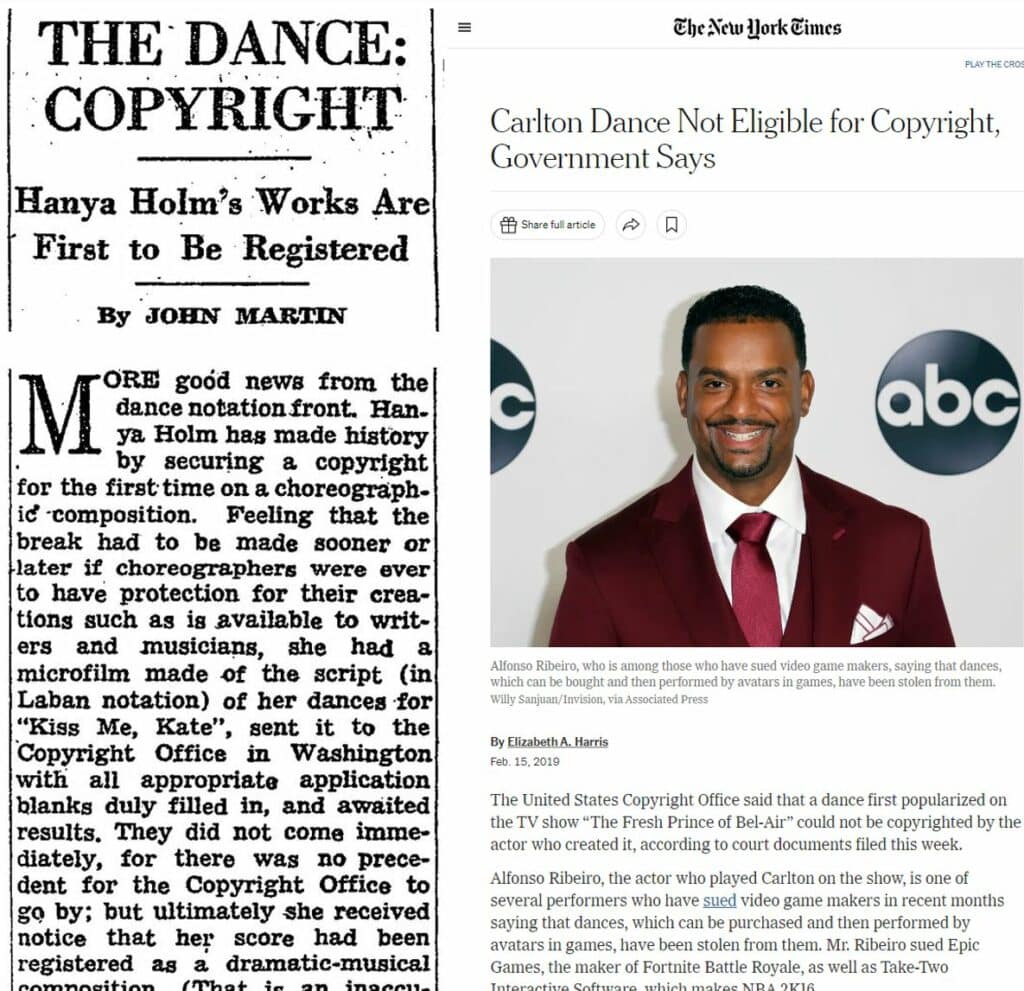

Choreography is like the Rodney Dangerfield of copyright law. It wasn’t until 1952 that modern dance pioneer Hanya Holm was able to secure the first ever copyright registration for her choreography of the Broadway musical Kiss Me Kate. It took another quarter-century for the U.S. Copyright Act to explicitly recognize standalone “choreographic works” as eligible for copyright protection.

Labanotation ain’t cheap, and since then, countless artists have elevated choreography to a real live art form while at the same time fighting an uphill battle for respect. From Michael Peter’s “Thriller,” to JaQuel Knight’s “Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It),” and of course Alfonso Riberio’s Fresh Prince “Carlton Dance,” choreography has become the oft-maligned red-headed stepchild of copyright.

That may be changing.

Hanagami v. Epic Games

On Wednesday, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals revived a copyright lawsuit brought by choreographer Kyle Hanagami (Blackpink, Jennifer Lopez, Britney Spears) against Fortnite publisher Epic Games. Hanagami first sued Epic in March 2022 over the Fortnite emote “It’s Complicated,” which Hanagami claims is an unauthorized copy of the choreography he published for the 2017 song “How Long” by Charlie Puth.

Here’s a video that Hanagami’s lawyer created comparing his choreography to the Fortnight emote:

Last year, Central District Judge Stephen Wilson dismissed Hanagami’s lawsuit, finding that the plaintiff had failed to plausibly allege that Epic’s emote was substantially similar to Hanagami’s registered choreography. The court found that the copied portion of Hanagami’s dance, “a two-second combination of eight bodily movements, set to four beats of music,” wasn’t protectable under the Copyright Act, and that “other than [these] four identical counts of poses . . . Plaintiff and Defendant’s works do not share any creative elements.”

But this week, the Ninth Circuit reversed (read the opinion here), finding that Judge Wilson got it wrong: “Short does not always equate to simple,” the court held. Unlike other routines that the Copyright Office has found uncopyrightable, like a “celebratory dance in the endzone,” Hanagami plausibly alleged that the copied portion of his dance “is a complex, fast-paced series of patterns and movements.”

To be sure, basic moves “consisting of ordinary motor activities, social dances, commonplace movements or gestures, or athletic movements” lack the requisite authorship to qualify for copyright protection. In other words, yoga positions, line dances and YMCA-type arm movements need not apply.

But recognizing that “the field of choreography copyright has remained a largely undefined area of law,” the court adopted the Copyright Office’s rather expansive definition of choreography as the “composition and arrangement of a related series of dance movements and patterns organized into a coherent whole.”

The key to the Court’s ruling is that it’s not merely static poses that should be considered when it comes to copyright and choreography. Rather, the Ninth Circuit held that lower courts should look at “body position, body shape, body actions, transitions, use of space, timing, pauses, energy, canon, motif, contrast, [and] repetition” when comparing two works. In addition, while isolated elements of a work aren’t protectable, a “choreographer’s selection and arrangement of the [work’s] otherwise unprotected elements” may be.

The decision doesn’t mean that Kyle Hanagami wins his lawsuit against Fortnite creator Epic. It just means he lives to fight another battle royale. Still, as far as choreography and copyrights are concerned, the Ninth Circuit’s opinion is a sashay toward respectability.

As always, let me know what you think in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media. In the meantime, here’s a copy of the full Ninth Circuit opinion in Haganami v. Epic Games.

View Fullscreen

4 comments

Does the short video contain the whole of the plaintiff’s allegedly protected work? If so, I think the District judge recognized correctly that in a case like this one, size matters! Beneath the doctrinal rhetoric, copyright is about awarding a monopoly. The ultimate question here is whether anyone in the Unites States who wants to use this brief set of physical motions must go to this plaintiff for permission. Relying on “selection and arrangement” doctrine begs that question.. I’d certainly like to hear from dance professionals about whether this short set of moves constitutes a “building block” of choreography. (Perhaps just an idea?) The brevity (and I’d guess the banality) of the set of motions suggests a “yes” answer. The opinion mentions the Led Zeppelin case. I think most guitar players recognized the claimant’s riff as brief and banal, as a building block. It shouldn’t have taken years of litigation to defend against that claim. I suspect the same point applies here. At a minimum, the protection should be very thin, lest the monopoly granted be truly excessive, setting off much future litigation. (If more of plaintiff’s work is at issue, then, obviously, this comment would need revision, but the principle at stake would be the same.)

Hi Jeremy,

I’d also like to hear from dance professionals as to whether these moves should be considered mere “building blocks” or something more – my sense is that professional choreographers would push back on the “banality” characterization. There’s obviously a continuum between unprotectable dance routines and protectable choreography, and this may be one of those situations in which an expert could be helpful in deciding where this falls along the line. Once you accept that choreography is made up of more than just “poses” (e.g., body position, body shape, transitions, timing, pauses, etc.) it begins to look more like a musical work in its variation and complexity. I’m not sure how much of that I’d appreciate as a judge or jury if it weren’t properly explained.

Hi, Aaron. Question: from your research would you agree that judges have been more inclined to dismiss (or grant SJ against) claims involving stories than those involving music? Storylines seem less technical and it’s easier for judges to recognize “ideas” and scenes a faire and to dismiss the claims with confidence. The need you and I express for professional dance advise illustrates the point. I’d feel more confident in saying–without expert help– “oh I’ve seen that plot line a dozen times in cop shows.” I suppose we can now expect an increase in “forensic dance witnesses” who get up and demonstrate their viewpoints. It will make for some very entertaining hearings!

I haven’t seen an empirical study of music vs. literary works cases, but anecdotally, I’d agree with you – although several recent unpublished Ninth Circuit cases have suggested that judges would benefit from expert testimony even in literary works cases: https://copyrightlately.com/ninth-circuit-substantial-similarity-pirates-caribbean-shape-water/