The Court finds that “leveling exorbitant settlement demands at nonprofits and public schools does not advance the purposes of the Copyright Act” after the plaintiff demanded $25,000 for a single Twitter post to a community swim account followed by 44 people.

Today’s post is a cautionary tale for plaintiff-side copyright lawyers. (And no, I’m not referring to anyone in particular.) It comes courtesy of a new ruling from the Northern District of California in which the court awarded $122,000 in attorneys’ fees following the successful defense of a copyright infringement claim against a nonprofit swim team.

“Winning Isn’t Normal”

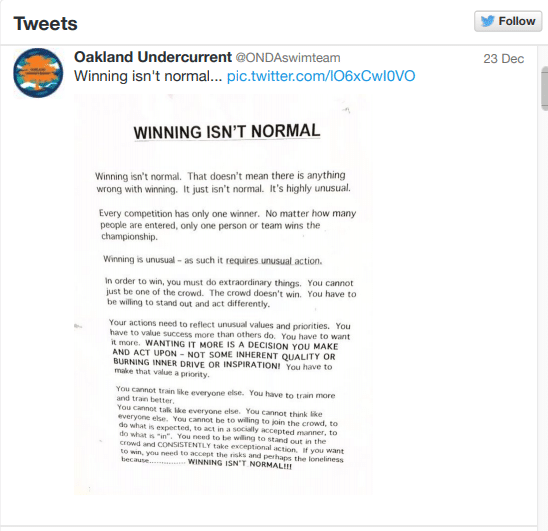

The plaintiff, Dr. Keith Bell, is a sports psychologist and performance consultant who published the motivational book “Winning Isn’t Normal” in 1982. The book contains a short passage that Bell refers to as the “WIN Passage,” which offers advice on winning:

Winning isn’t normal. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with winning. It just isn’t the norm. It’s highly unusual …. In order to win, you must do extraordinary things. You can’t just be one of the crowd. The crowd doesn’t win. You have to be willing to stand out and act differently.

Dr. Keith Bell, “Winning Isn’t Normal”

Oakland Community Pools Project

The defendant, Oakland Community Pools Project (“OCPP”) is a nonprofit organization. OCPP operates the Oakland Undercurrent youth swim team, which provides local youth the opportunity to participate in swim events and lessons they wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford.

OCPP has a Twitter account to keep swim team members and their families informed about various events. In 2015, OCPP’s head coach posted an image of the WIN Passage on the group’s Twitter feed in an effort to “educate and motivate” members of the swim team. The coach claimed that he wasn’t aware of the author or origin of the passage at the time he posted it.

Notably, at the time the WIN Passage was posted, OCPP’s Twitter account only had 44 followers, none of whom had liked, shared or commented on the allegedly-infringing post. Maybe they didn’t find it inspiring enough?

Dr. Bell discovered the tweet in January 2016. His lawyer sent OCPP’s coach a cease and desist letter over a year later, demanding that he remove the post and pay Bell $25,000 to resolve the case. OCPP deleted its post after receiving the letter, but didn’t pay. Bell waited until 2019 to file a lawsuit for copyright and trademark infringement against OCPP.

The Statute of Limitations in Copyright Cases

During the course of litigation, the parties each filed motions for summary judgment. OCPP argued that Bell’s claim was barred by the statute of limitations, which requires that copyright infringement claims be “commenced within three years after the claim accrued.” Generally, a copyright claim accrues and the statute of limitations begins to run when a party discovers, or reasonably should have discovered, the alleged infringement. Here, Bell first discovered the allegedly infringing Twitter post in January 2016, but didn’t file his complaint for copyright infringement until March 2019—over three years later.

I should point out that the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer made it much easier to state a claim for copyright infringement even decades after the fact. There isn’t a “single publication rule” for copyright law as there is with torts like defamation. Some scholars have argued that keeping an infringing article on your website can effectively extend the statute of limitations indefinitely.

That said, courts are split on whether a separate display violation occurs each time a user views a work online. Some courts have found that there needs to be evidence that the defendant engaged in new affirmative acts of infringement to reset the limitations clock. Others have held that each time a user accesses an allegedly infringing work online, this extends the statute. The court in Bell rejected the latter approach. Because OCPP didn’t itself commit a new act of infringement after Bell first discovered the post in January 2016, the court found that the statute of limitations started then.

In May, the judge granted OCPP’s summary judgment motion on statute of limitations grounds, which ended the case in OCPP’s favor. As the prevailing party, OCPP filed a motion to attorneys’ fees, which the court has just decided (read here).

Attorneys’ Fees in Copyright Cases

Fee awards in copyright cases are discretionary, with judges examining such factors as the degree of success achieved by the prevailing party, whether the case was frivolous, whether the losing party’s arguments were objectively unreasonable and the motivation of the parties in pursuing the action. Judges will also look to considerations of compensation and deterrence by asking, for example, whether a fee award in a particular case would discourage copyright owners from seeking to enforce rights in their works.

Here, the court noted that even though OCPP had prevailed on a technical defense (statute of limitations) as opposed to the merits, it obtained judgment on the entire case in its favor. Therefore the “degree of success” factor weighed in OCPP’s favor.

However, the court also found that Dr. Bell’s copyright claim was not “frivolous” nor were his statute of limitations arguments “objectively unreasonable” in light of the split in authority I mentioned above. These factors therefore weighed in favor of the plaintiff.

The Plaintiff’s Improper Motivation

The court slammed Dr. Bell on the “motivation” factor. It agreed with OCPP that his lawsuit was driven primarily by a desire to force his opponent to choose between spending money to defend itself and paying a settlement fee grossly disproportionate to the severity of its conduct.

The court also noted that this was not the first time Bell had used this tactic, bringing more than 26 other lawsuits and obtaining settlements from at least 90 different alleged infringers, all relating to the WIN Passage. The court said that Bell’s claims all appeared to be designed to extract a quick settlement in exchange for an amount that was just cheap enough to discourage his targets from mounting a fair use defense.

Leveling exorbitant settlement demands at nonprofits and public schools does not advance the purposes of the Copyright Act.

Bell v. The Oakland Community Pools Project, Inc.

To be clear, the fact that a copyright is frequently infringed or that a copyright owner wants to obtain compensation for that infringement doesn’t necessarily mean that the plaintiff’s motives are improper. But in Dr. Bell’s case, the court found that his actions suggested he was in the business of litigation, as opposed to being motivated by a genuine desire to protect his copyrights.

For example, in a case in Utah, Bell had alleged that employees of a public school infringed his copyright by reading an excerpt from “Winning Isn’t Normal” at a football awards banquet—a claim that he settled for $600 after the school district filed a counterclaim. There was also evidence that Dr. Bell had a particular strategy of pursuing copyright claims against swim teams, because they often had insurance that could contribute to a settlement payment.

And, as noted, Dr. Bell sought a large settlement against OCPP based on a Tweet posted to a group of only a few dozen followers. OCPP submitted an expert report in connection with its summary judgment motion estimating that a reasonable licensing rate for posting a short passage from a book like Dr. Bell’s would be $12.83. This was obviously a far cry from the $25,000 Bell demanded—a figure the court found “bordered on the extortionate.”

Finally, the court rejected Dr. Bell’s suggestion that a fee award would deter “starving artists” from defending their copyrights. Bell wasn’t a starving artist, and given his litigation strategy, a fee award would discourage serial litigants from bringing unmeritorious suits and then unnecessarily driving up litigation costs in order to drive a settlement.

The Court’s Fee Award

While representing the defendant pro bono, its attorneys submitted the billings that they would have charged had OCPP been a paying client. After discounting the amounts somewhat, the court found that the successful defense merited an award of $122,101.65 in attorneys’ fees and costs. This is a particularly striking sum given the nature of the case, but then, so was the plaintiff’s settlement demand. The court’s decision will likely cause copyright plaintiffs to think twice about bringing these kinds of cases—or at least in demanding huge settlement payments up front.

After all, in the words of Dr. Bell, “winning isn’t normal.” But, I should also add, losing isn’t cheap.

As always, let me know what you think. Use the comments below or send me a message (preferably one that’s non-infringing) on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn or Facebook. Also, a reminder that I send out a newsletter with exclusive subscriber content every Sunday, so sign up if you haven’t!