Atari’s copyright infringement lawsuit against State Farm advances, underscoring the importance of careful clearance in advertising.

It looks like Jake from State Farm is definitely going to blow through his deductible, as the insurance giant lost its bid to declare game over on a lawsuit brought by video game publisher Atari Interactive. On Friday, a Texas federal judge dismissed much of the case but kept Atari’s core copyright infringement claim in play.

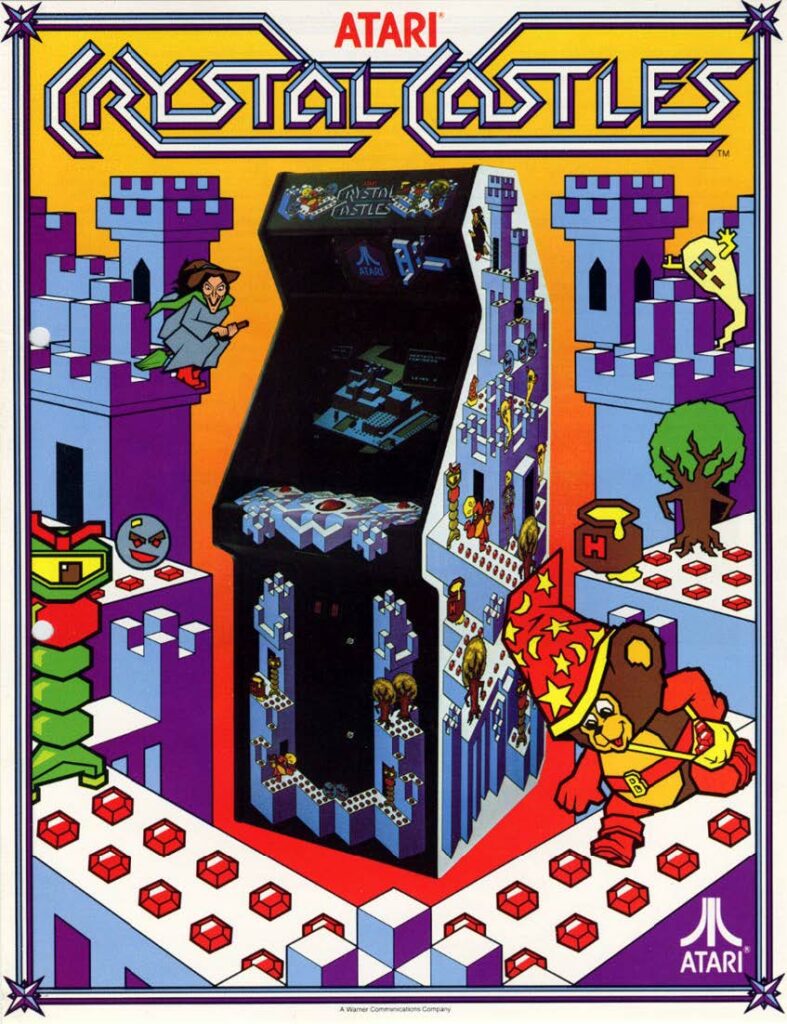

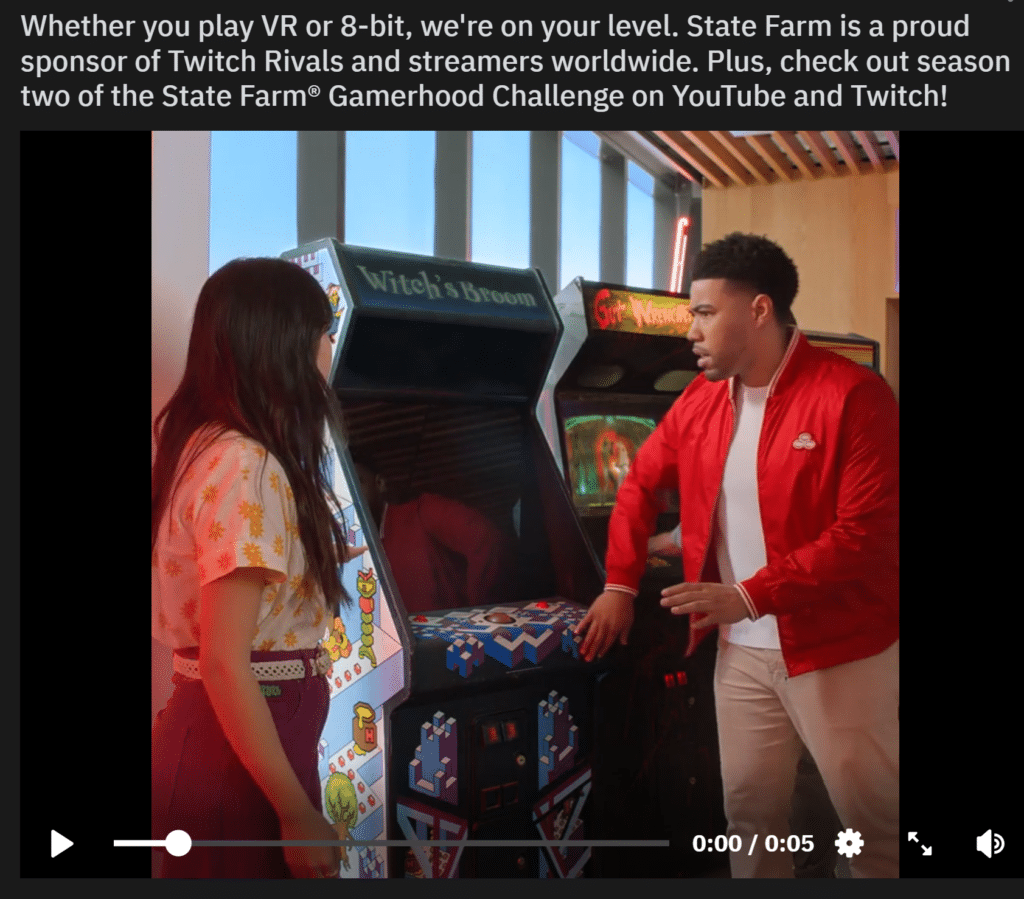

I first wrote about this case back in March, when Atari filed a complaint accusing State Farm and its advertising partners of improperly appropriating artwork from Atari’s 1983 arcade game “Crystal Castles” for a 6-second online video advertisement. Atari claimed that the ad, which featured a modified version of a Crystal Castles arcade cabinet, was part of a “cynical plot” to capitalize on retro gaming nostalgia and resonate with fickle millennial and Gen Z consumers. State Farm changed the name of the game to “Witch’s Broom” on the cabinet’s marquee, but left portions of the game’s original cabinet artwork visible—likely an oversight, but one that may prove costly for the defendants.

In addition to copyright infringement, Atari brought claims for business disparagement, false information and advertising, unfair competition, and unjust enrichment. Atari asserted that State Farm’s ad damaged its brand by showing the company’s khaki-clad spokesperson “Jake from State Farm” smacking the machine to get it working—implying that Atari’s products were unreliable and outdated.

In May, State Farm filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit (read here), arguing that Atari was “seeking a windfall for the inadvertent and fleeting use of a decades-old arcade game.” The company claimed the ad’s use of the Crystal Castles cabinet was de minimis—too fleeting and trivial to constitute infringement—and that it was protected under the fair use doctrine, asserting that the commercial had no conceivable impact on the market for Atari’s game. As for the business disparagement claim, State Farm argued that there was no malicious intent or false statement about Atari, and that the lighthearted tone of the ad didn’t suggest any serious defects in the company’s products.

The Court’s De Minimis Analysis

In an opinion penned by Northern District of Texas Judge Sidney Fitzwater (read here), the court allowed Atari’s copyright claim to proceed. First, the court wasn’t convinced that State Farm’s use of the Atari cabinet was de minimis, emphasizing that the cabinet’s artwork—despite the name change—remained recognizable and prominently displayed in the center of the ad. The court noted that determining whether a use is de minimis involves both quantitative and qualitative assessments—how much of the copyrighted material was copied and how significant that copying was.

For visual works, courts typically evaluate factors such as prominence, clarity, and the length of time the copyrighted material appears in the allegedly infringing work to determine whether actionable copying has occurred.

In practice, it’s difficult to predict how courts will come out on a de minimis defense. For example, in Gottlieb v. Paramount Pictures, the court found that the appearance of the plaintiff’s “Silver Slugger” pinball machine in the background of a scene from the Mel Gibson rom-com What Women Want was de minimis. That court emphasized that the machine was always in the background, partially obscured and out of focus, and played no role in the plot. Conversely, in Ringgold v. Black Ent. Television, the court held that artwork shown in the background for 27 seconds in an episode of ROC was sufficiently recognizable to cross the de minimis threshold for actionable copying of protected expression.

In Atari’s case, Judge Fitzwater noted that the Crystal Castles arcade cabinet appeared in the center of nearly every frame of State Farm’s ad, even though parts of the design were obscured by actors and the marquee was replaced with a different title. The artwork was observable and in focus for the majority of the ad, which increased its qualitative significance. The court also noted Atari’s allegations that some viewers had identified the cabinet as Crystal Castles, even with the changed marquee. As a result, the court found that Atari had plausibly alleged that the copying exceeded the threshold of de minimis use and allowed the copyright claim to move forward.

The Fair Use Defense

The court also denied State Farm’s motion to dismiss Atari’s copyright claim based on the fair use defense. Here’s how the court evaluated the four factors of the fair use test:

Purpose and character of the use: The court emphasized that State Farm used the arcade cabinet wrap in a commercial advertisement, which weighed against fair use. The judge also wasn’t convinced that the artwork was used for a transformative purpose, such as commentary or criticism, but rather to invoke the same aesthetic tones as the artwork itself, which weighed against a finding of fair use.

Nature of the copyrighted work: The court found that because Atari had plausibly alleged that the defendants had appropriated the expressive elements of the cabinet wrap, this factor also weighed against fair use.

Amount and substantiality of the portion used: Although the marquee of the arcade machine was altered, the court stressed that much of the cabinet’s artwork was still visible and recognizable. The court also noted Atari’s allegation that viewers were able to recognize the artwork as coming from Crystal Castles, so this factor also weighed against fair use.

Effect on the market: Atari alleged that it has an active licensing business extending its brand into advertising, merchandising, and other areas. The court found it plausible that State Farm’s unlicensed use of the Crystal Castles artwork could impact this licensing business. Accepting Atari’s allegations as true for purposes of the motion to dismiss, this factor weighed against fair use as well.

While the court didn’t reject the defense outright, it found that Atari hadn’t “pleaded itself out of court by admitting all of the elements of the fair use defense,” and that the fair use question couldn’t be resolved at the motion to dismiss stage.

Other Claims: Dismissed

The court was less forgiving when it came to Atari’s other claims. The judge dismissed the business disparagement, false advertising, unfair competition, and unjust enrichment claims. Most notably, Atari had alleged that State Farm’s ad “placed Atari and its works in a bad light, including when the ‘Jake from State Farm’ character hits the front of the cabinet—right on Atari IP—suggesting falsely and disparagingly to consumers that Atari’s cabinets are low-quality, faulty, and/or unreliable.”

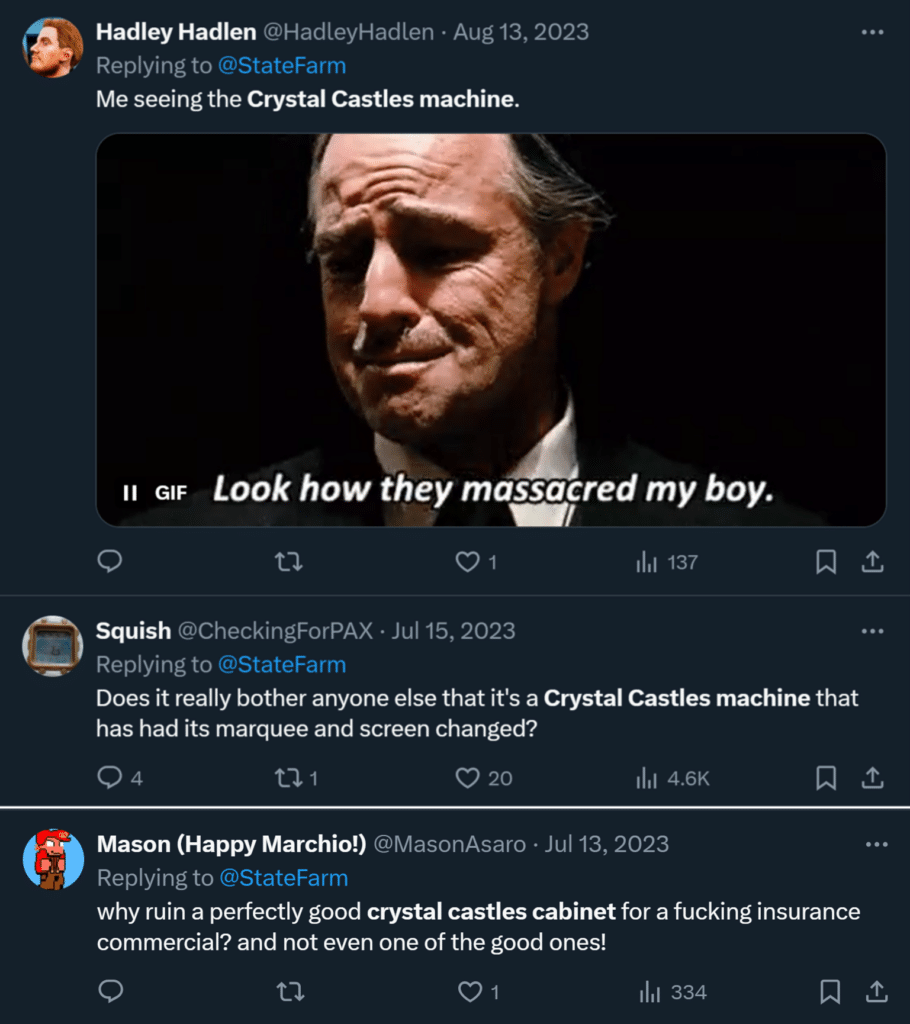

However, while Atari asserted that certain individuals on social media expressed their dissatisfaction with State Farm’s use of the Atari cabinet, the court found that these statements didn’t suggest that the dissatisfaction was directed at Atari or that Atari lost any customers, revenue, or goodwill as a result of the ad’s depiction of its arcade machine.

The Bottom Line

Atari Interactive v. State Farm serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of properly clearing intellectual property rights before using iconic imagery in ads. Any props or set pieces appearing in advertising should either be licensed from the rightsholders or appropriately obscured or eliminated before an ad is finalized. The idea isn’t to successfully defend a copyright lawsuit but to avoid an unforced error in the first place.

To be clear, Atari isn’t blameless in all of this either. Its lawsuit comes across as an opportunistic attempt to profit from State Farm’s mistake rather than a legitimate effort to protect its copyright from real market harm. I suspect the vast majority of people who viewed State Farm’s ad didn’t even notice the Crystal Castles artwork, let alone know where it came from.

Still, what may seem like a harmless nod to a vintage game could quickly turn into a costly legal headache if standard clearance protocols aren’t followed. Whether State Farm will settle this dispute or continue to litigate remains to be seen. My bet’s on a relatively quick settlement, but one thing is clear—this is one insurance ad that just wasn’t worth the risk.

As always, feel free to share your thoughts in the comments or on social media @copyrightlately. In the meantime, a copy of the court’s opinion is below.

View Fullscreen