A court win against the Internet Archive has publishers celebrating, but what does it mean for the future of public libraries and digital access?

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has spoken, and it’s not the news advocates of “controlled digital lending” were hoping for. In last week’s ruling in Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive (read the opinion here), the court dealt a decisive blow to the Internet Archive, ruling that its practice of scanning and lending digital copies of books doesn’t qualify as fair use under the Copyright Act. It’s a clear win for publishers, but for public libraries—and the millions who rely on them for access to digital books—the ruling may signal more troubling times ahead.

Controlled Digital Lending: A Quick Refresher

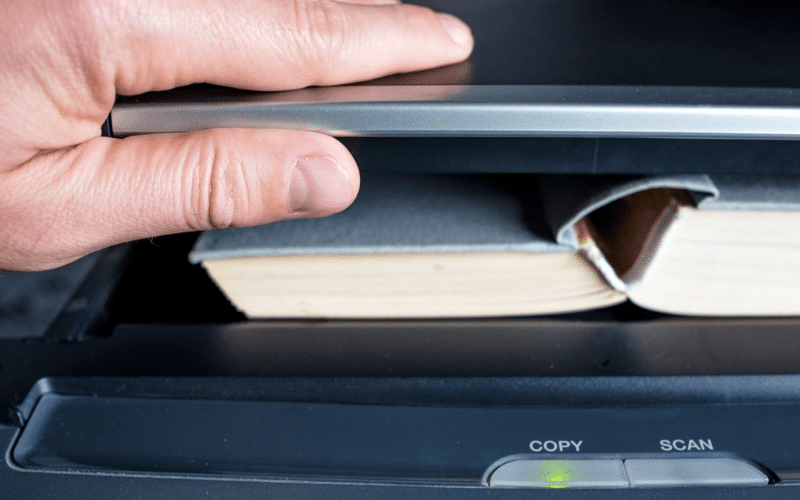

Controlled digital lending (CDL) is a model in which libraries scan physical copies of books they’ve legally acquired and then make the resulting digital versions available for borrowing. When the electronic book is “checked out,” the physical copy is removed from circulation. Once the loan period ends, the digital book is “returned” and becomes inaccessible to the borrower. The theory behind CDL is that by maintaining a consistent “owned-to-loaned” ratio between physical books and digital copies, libraries can meet the digital needs of twenty-first-century patrons without violating existing copyright law.

At least, that was the idea.

In practice, several aspects of CDL have left it exposed to legal attacks. Despite its name, controlled digital lending doesn’t merely involve lending but copying as well. If libraries could lend electronic works without copying them, they surely would, but the digital format doesn’t work that way. Books are copied when they’re scanned and converted into electronic files in the first instance, and at least one additional copy is made when a file is accessed or stored on a borrower’s device.

The reproduction aspect inherent in CDL also highlights an important legal distinction between digital and print works more generally. Physical books that have been lawfully acquired are subject to the Copyright Act’s “first sale doctrine,” which means that any particular copy of a physical book may be sold, given away, or loaned without the copyright owner’s permission. However, the first sale doctrine only applies to distribution rights—it doesn’t cover reproduction rights. Plus, it doesn’t apply to licenses, which have become the primary means for distributing and monetizing e-books.

Internet Archive’s “Open Library” Project

Historically, copyright owners haven’t pursued infringement actions against the relatively few traditional libraries that have tried some form of CDL, leaving the model legally untested in court.

This all changed in June 2020, when four of the largest book publishers (Hachette, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House) filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Internet Archive (IA). In addition to maintaining its well-known “Wayback Machine,” the San Francisco-based nonprofit has spent the last decade scanning millions of print books and making the resulting electronic scanned versions publicly available on archive.org and openlibrary.org.

IA’s Open Library project includes millions of public domain books that users can download and read without restriction. It also includes 3.6 million additional books protected by valid copyrights. For these, IA claims it follows CDL principles by only simultaneously lending as many digital copies as it has in print.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which shut down libraries nationwide, leaving up to 650 million print books out of circulation. Seeing itself as “uniquely positioned to be able to address this problem quickly and efficiently,” IA launched what it called the “National Emergency Library” (NEL). NEL essentially took the “controlled” out of controlled digital lending. Instead of enforcing a one-to-one owned-to-loaned ratio, IA allowed up to 10,000 users at a time to borrow each of its books.

Publishers weren’t happy. They sued, alleging that IA’s digital lending was piracy disguised as philanthropy.

Hachette v. Internet Archive

Last year, Southern District of New York Judge John Koeltl ruled on summary judgment for the publishers, finding that all four fair use factors weighed strongly in their favor. On September 4, the Second Circuit affirmed.

On the first fair use factor (Purpose and Character of the Use), the appellate panel found IA’s use noncommercial (breaking from the district court on this point) but emphasized that post-Warhol, the key question is whether the secondary use serves a “transformative” purpose. Here, the court sided with the publishers, finding that “IA’s digital books serve the same exact purpose as the originals: making authors’ works available to read” without adding any new meaning or expression.

On the fourth factor (Effect on the Market), the court found that IA’s extensive copying and distribution harmed the markets for both print and digital books. By offering unrestricted access to the copyrighted works without paying the customary licensing fees, the court held that IA undercut the publishers’ ability to monetize their content. The court gave especially short shrift to the claimed public benefit of IA’s library, writing: “Libraries and consumers may reap some short-term benefits from free digital books, but what are the long-term consequences? If authors knew their works could be copied and distributed for free, there’d be little incentive to create new ones.”

That last statement seems highly doubtful, but if true, it would apply to traditional lending by traditional libraries as well.

So let’s talk about libraries. It’s been said that if public libraries didn’t already exist, they’d be found unlawful today. While that may seem like an exaggeration, the tension between the goals of public libraries and the realities of copyright law has never been more apparent.

Libraries Caught in the Crossfire

After years of CDL flying under the radar, IA’s massive digitization project ended up being the poke that woke the sleeping giant. If we’re being honest, the NEL was essentially an invitation to be sued, making it counterproductive for the actual libraries that need workable solutions for transitioning from print to digital.

Here’s the thing: With print, it’s straightforward—libraries buy a book once and can lend it out as many times as they want, as long as that copy holds up. But with e-books, the rules change dramatically. Publishers have realized that e-books offer something that print books don’t—control. By licensing e-books rather than selling them outright, publishers can dictate how long a library can lend a digital book, how many times it can be borrowed, and at what price.

For example, according to a study by the American Library Association, HarperCollins offers e-book licenses that allow a book to be lent just 26 times before the library is required to get a new license. Publishers like Hachette and Penguin Random House have adopted two-year licenses, after which libraries must repurchase access. This licensing model often results in libraries paying three to ten times more for digital books than for physical copies. The pandemic only made things worse, with skyrocketing demand for digital content forcing libraries to stretch already strained budgets even further.

A recent Library Journal survey found that libraries now allocate nearly 27% of their materials budgets to digital content, with suburban and urban libraries dedicating up to 30%. And since publishers often charge libraries more for e-books than they do for print editions—or even consumer e-books—the costs add up quickly. For example, a physical copy of James Patterson’s The #1 Lawyer costs $18. The Kindle version is available to consumers for $14.99. Hachette (through the OverDrive intermediary) charges libraries $65 for a two-year license, allowing the book to be loaned to one patron at a time.

To be sure, the per-user cost is lower, but not nearly as low as the per-user cost on the print edition. Plus, the digital licenses are temporary and subject to increasing costs every two years. It’s no wonder that digital content is eating up a growing share of library budgets. But what’s worse is that as libraries spend more on e-books, they’re forced to cut back on other areas—whether that’s acquiring new titles, offering community programs, or simply keeping the lights on.

Beyond the Courtroom

While the Hachette v. Internet Archive ruling is undoubtedly a legal victory for the publishing industry, the broader question remains: How will libraries continue to serve their communities in the digital age, and what role will publishers play in shaping the future of access to knowledge?

It’s crucial to recognize that short-term profit motives may have negative long-term effects. After all, libraries are where many people, especially young readers, learn to develop a lifelong love of books. I still remember the day I got my first library card, amazed by the world of knowledge and discovery that greeted me at my neighborhood library. By making digital access more expensive and restrictive, publishers may unintentionally stifle the development of future readers, especially in less affluent neighborhoods. This may actually harm book sales in the long run. In addition, libraries have historically fostered literacy and provided access to books in underserved communities. If digital access becomes prohibitively expensive, this role could be compromised.

Controlled digital lending may not be the solution. Mass unpermitted digitization certainly isn’t. But we owe it to future generations to figure out what the solution is. Book publishers can celebrate their legal victories, but let’s give libraries a reason to celebrate too.

As always, I’d love to know what you think. Hit me up in the comments below or @copyrightlately on social media.

View Fullscreen

8 comments

Another big issue (especially for academic libraries) is that many titles are not available for libraries to purchase as ebooks. How can we support our distance learning students with digital access?

It might become the case that only works without copyright protection will become easily available digitally in the future. If you wanted any book that still has copyright protection, you might be forced to find a physical copy, on Amazon or wherever. This will in the long run cause fewer books to be published as more and more people simply are no longer interested in physical books. Digital or they go elsewhere, and there is a lot of elsewhere to go to. Maybe the time has come to recognize that you go with the medium the audience desires. The world has changed, and maybe the traditional form of publishing is no longer viable. Copyright laws were written when copying was essentially impossible except by hand, maybe now the only reward for authors will be reputational, not monetary as reproduction is incredibly easy, “legal” or on a personal basis.

It’s not the major point of this case, but I find it interesting and confusing that this and other opinions treat a change in format as a derivative work. It’s true that the definition in the Copyright Act speaks of “any other form in with the Work may be recast.” But I wonder if that language was intended to mean, say, physical copy to digital copy. Aaron, remind me, has this been the law for a long time or is this a recent view? It seems to me that a digital copy of a physical book is just another copy of the work in question, not a derivative work. And there is a difference between a derivative market and a derivative work. The fourth factor protects derivative markets which often but need not involve a derivative work. I don’t think is quibbling. There is enough confusion without adding this one! But I don’t wear a robe so my opinion is what it is! Thanks for the excellent essay on this case, including your astute thoughts about the need for some sort of middle ground….

Yeah the Second Circuit has been saying for 10 years (since the HathiTrust case) that the “recasting of a novel as an e-book or an audiobook” is a derivative work. This is at least the third time since then that the court has used this formulation. I agree that it seems to differ from the way older cases, at least in the Ninth Circuit, used to analyze the issue.

I agree the Hachette court saying that an ebook is a derivative work is very puzzling. We recently blogged about this exact issue! https://www.authorsalliance.org/2024/10/07/what-is-derivative-work-in-the-digital-age/

Hi. Thanks for this article, it made me think! But I do wonder about this (as a non-lawyer but long-time licensing expert in the publishing industry): Didn’t the DMCA amend section 108 to allow libraries and archives to reproduce copies of their print collection digitally without permission so that they could preserve their collection (and continue to make it available to the public)? I know that the license terms between publishers and libraries for digital copies has long been a very very sticky wicket, but I am not sure that about your argument that this might sound a death knell for libraries in general.

Yes, the amendment to section 108 allows up to three copies, which may be digital — but only provided that the digital copies are not made available to the public outside the library premises — so I’m not sure how that solves the issues of increased costs.

I recently moved, and had over fifteen thousand books, most out of print. I painstakingly checked each beloved title I was giving/donating away on Internet Archive to make sure I still had access to the title.

I also have severe allergies as well as vision problems, and the Internet Archive was a Godsend to me. Everything I read is out of print, or the particular edition( translator, illustrator) is unavailable.

The real book lovers and the elderly are the ones most hurt by this new ruling.

After downsizing, I no longer have hard copies of these books; libraries only keep most books around ten years, and now these wonderful books are unavailable tome.