88 painted tote bags designed by artist David Lew (aka “Shark Toof”) are at the center of a new copyright lawsuit brought under the Visual Artists Rights Act against the City of Los Angeles and the Chinese American Museum.

Cheese walls are apparently yesterday’s moldy Limburger when it comes to the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). The newest complaint to push the envelope under a federal law designed to prevent the “destruction of a work of recognized stature” seeks damages for an artist’s original art design placed on now-thrown out tote bags.

The plaintiff in the new lawsuit, filed Wednesday in federal court in Los Angeles, is artist David Lew, known professionally as “Shark Toof.” Lew’s complaint arises out of a 2018 art exhibition sponsored by the Chinese American Museum of Los Angeles (CAM) called “Don’t Believe the Hype: LA Asian Americans in Hip Hop.” Lew, who is known for his murals, spray paintings and wheat pastes, was one of the Asian American artists asked to showcase original art for the exhibition.

Lew’s Complaint

According to the complaint, in December 2018, someone allegedly acting on behalf of CAM or El Pueblo ordered trash removal crews to “take down, discard, and destroy” Lew’s original artwork. At least 74 of the 88 pieces were in fact thrown out.

Lew filed a formal claim with the City of Los Angeles, which allegedly pointed the finger at CAM, which then pointed the finger back at the City. Unable to resolve the matter, Lew proceeded, in the immortal words of Sol Rosenberg, to “sue everybody.”

The Visual Artists Rights Act

As I explained in my article on Cavallaro v. SLSCO, Ltd., aka the “cheese wall” case, VARA is a section of the Copyright Act that allows qualifying authors of works of visual art of “recognized stature” to prohibit the “intentional or grossly negligent destruction” of their works. The law has left it to courts to determine what works qualify as those of “recognized stature.”

Lew’s lawsuit also includes several California state law claims, including causes of action under California’s Art Preservation Act (Civil Code section 987) (CAPA), which protects against the intentional or grossly negligent desecration of works of fine art. VARA and CAPA overlap to a large extent, and when they do, the federal law preempts the state statute.

The “Shark Toof” case raises a number of interesting issues on first read.

First is the fact that Lew’s suit was filed against the City of Los Angeles. This isn’t improper, but it isn’t something you see every day. While states are immune from copyright infringement claims (as confirmed by the Supreme Court earlier in 2020), sovereign immunity doesn’t extend to cities and municipalities.

Second is the issue of whether Lew’s work qualifies as a “work of recognized stature” under VARA. This seems doubtful, but I’m sure Lew will attempt to present testimony by art experts or members of the artistic community if the case gets that far.

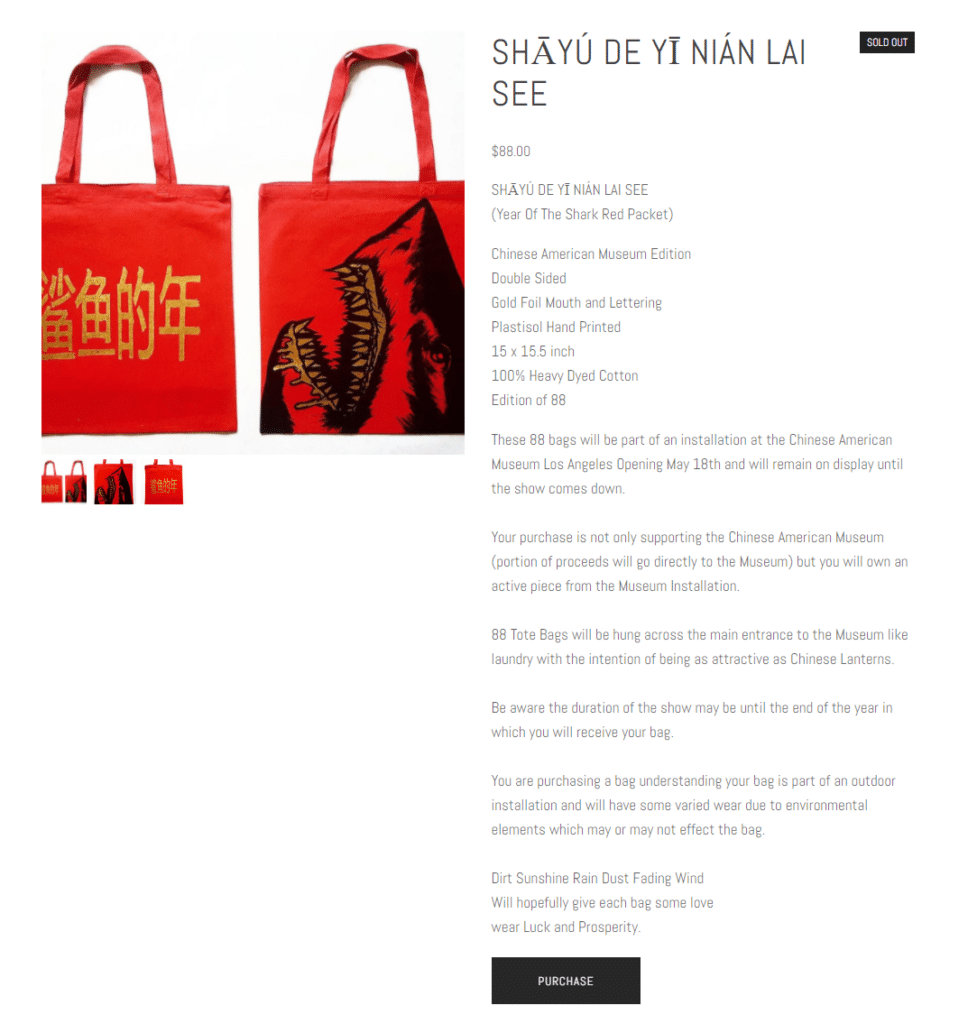

Third, judging from the images in the complaint and on Lew’s website, each of the 88 pages contains the same painted design. This isn’t necessarily a problem, as the Copyright Office defines a “work of visual art” as “a painting, drawing, print, or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer.” However, to qualify, each of the copies needs to be “signed and consecutively numbered by the author” and I don’t see any signatures on these works.

VARA and Applied Art

The most interesting question, however, is whether VARA can protect artwork affixed to tote bags in the first place. Note that VARA doesn’t define “work of visual art.” Section 101 of the Copyright Act does helpfully note that a “work of visual art” does not include a work of “applied art.” Less helpful is the fact that the term “applied art” isn’t defined in VARA or anywhere else in the Copyright Act. (And you all still ask why there’s so much litigation out there?)

A few courts have taken up the task of defining “applied art” for purposes of VARA, including the Ninth and Second Circuits. According to these courts, an object is “applied art” if it (1) initially served a utilitarian function and (2) continues to serve a utilitarian function after the artist made embellishments or alterations to it.

As an example, in Cheffins v. Stewart, the Ninth Circuit held that a used school bus outfitted to look like a Spanish galleon was “applied art” and therefore not protectable under VARA. The bus was an art installation for use at the Burning Man festival. The court held that the bus “retained a largely practical function even after it had been completed,” because it continued to be used for transportation, to host musical performances and weddings, and as a stage for poetry and acrobatics shows.

Lew’s “Tote Bag Release”

So what about Lew’s “Year of the Red Shark Packet?” The complaint studiously avoids referring to Lew’s works as tote bags, as opposed to artwork that simply happens to be placed on tote bags. And there’s one fact that the complaint ignores altogether, which is that Lew offered all of these artworks for sale on his website (for $88 each) before they were destroyed, as part of a “tote bag release.” Lew’s offering touted the dimensions of the bags and the fact that they were made of “100% Heavy Dyed Cotton”—which doesn’t matter a whole lot if they’re works of art, but which probably does matter if you’re looking for a heavy duty (i.e., utilitarian) bag.

When I tried to add one of Lew’s bags to my virtual shopping cart, I was told that they were all out of stock. On an Instagram post, Lew expressed his apologies to “all of my collectors who purchased and supported this installation which will …. require refunds to assure good faith in my collectors.”

My Take

While I do commiserate with Lew’s loss, I have serious doubts as to whether a statute like VARA—which is already so fundamentally at odds with the rest of the United States’ economically-based approach to copyright—should apply to what appears to be a primarily monetary loss. If the plaintiff is able to demonstrate that his property was in fact disposed of wrongfully, the case is better suited to a cause of action for conversion—which his complaint also alleges.

Lew stood to make $88 for each of his 88 bags (just shy of $8,000), and yet per VARA he’s claiming statutory damages under the Copyright Act that range between $750-$30,000 per work, an amount which can be increased in cases of willfulness up to $150,000 per work.

Don’t think that’s possible? In the recent “5Pointz” case, Castillo v. G&M Realty, the Second Circuit affirmed a $6.75 million judgment against a real estate developer for willfully violating VARA rights for 45 works of visual art. The defendant’s conduct there was particularly egregious, but the prospect of the City of Los Angeles being forced to pay a minimum of $66,000 up to $2,600,000 in non-willful statutory damages for conduct that may have been negligent at worse seems like a pretty tough pill to swallow. It also represents a windfall to Lew, who had appears to have sold most if not all of his bags at the time they were thrown out.

Even more importantly, allowing an artist to bring a VARA claim in a case like this could lead to some pretty troubling consequences. Imagine that you’re a purchaser of one of Shark Toof’s $88 pieces of art, which you use to lug around your bowling ball, causing the bottom to fall out. In a fit of disgust you throw your now (decidedly less functional) tote bag in the garbage. Not only are you out one very expensive bowling ball carrier, but you may face hundreds of thousands of dollars in copyright infringement damages as well. That’s one shark toof that’s going to leave a pretty bad bite mark.

Am I way off base here? Let me know in the comments below or on one of the Copyright Lately social media accounts.

View Fullscreen