A 👩🏽 has 📁 a 🏛️💼 against 🍎 for copying her 🧑🏾. Does she have a ✔️💼 for ©️ infringement?

So, I will confess that I had originally planned to write this post entirely in emoji, until I realized that I didn’t know the symbol for “idea/expression dichotomy.” You can thank me later.

UPDATE—Well, it only took a year and a half, but the court has dismissed the emoji lawsuit against Apple. Read the court’s order here.

The Emoji Lawsuit

Last week, Cub Club Investment LLC (CCI), a company owned by businesswoman Katrina Parrot, filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Apple (copy here) in the Western District of Texas. According to the complaint, Parrott came up with the idea to create a set of “racially diverse” emoji featuring different skin tones after her daughter wondered why emojis don’t look like the person sending them. (I’m going to go ahead and assume that Parrott’s daughter is not Lisa Simpson.)

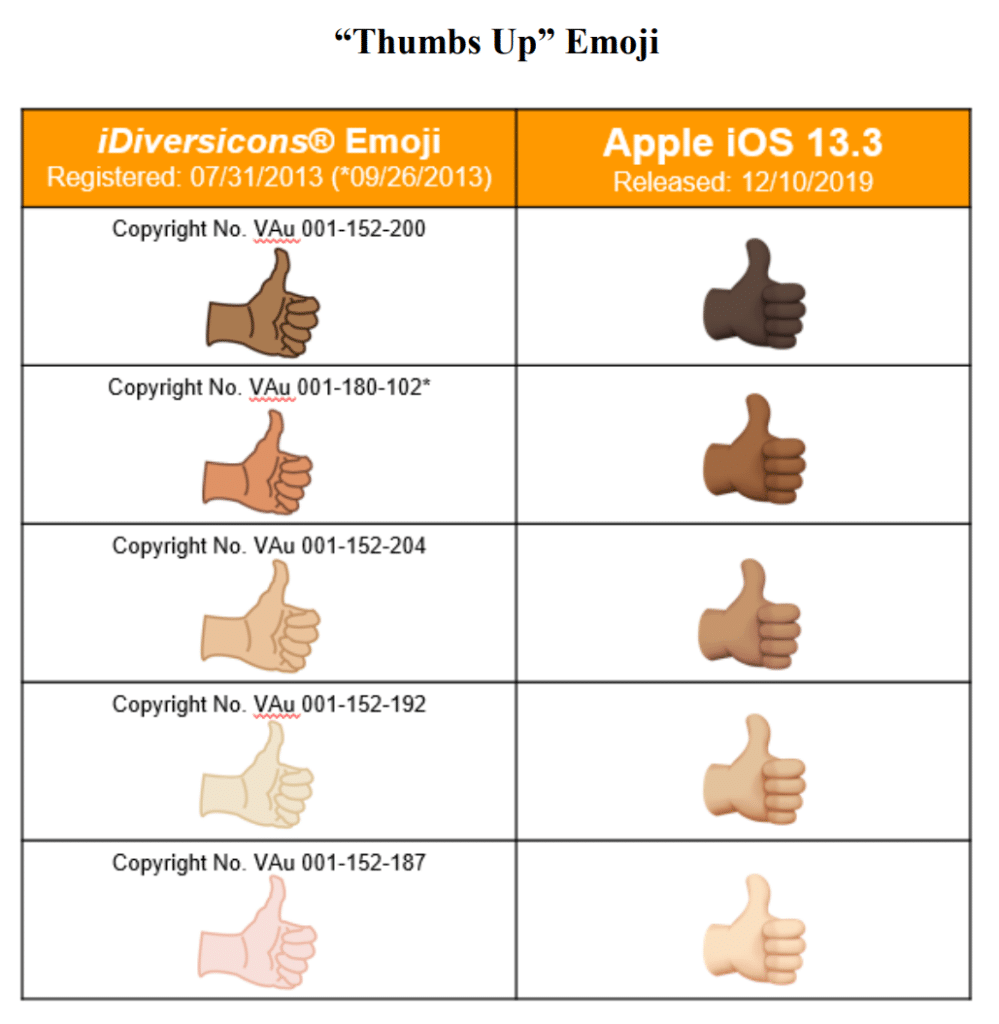

After registering copyrights in several of her emoji, Parrott launched “iDiversicons” on Apple’s App Store in 2013. iDiversicons featured various emojis in five different shades, comprised of “an African-American tone, Asian tone, Latino/Hispanic tone, Indian tone, and Caucasian tone.”

CCI’s complaint alleges that in 2014, Parrott had discussions with Apple about entering into a potential partnership to use her diverse emoji in Apple’s products. However, after some initial discussions with an Apple software engineer, Parrot was told that the company was developing its own set of diverse emoji, which Apple released in 2015.

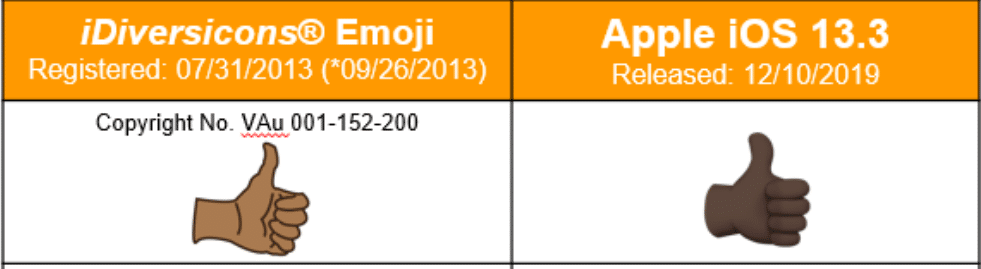

CCI (a company owned by Parrott and to which she assigned her copyrights) contends that Apple infringed the iDiversicons emoji. The complaint includes side-by-side depictions of some of the alleged infringements.

Ideas, Natural Objects and Thin Copyrights

Does CCI have a 💼? Sorry, a case?

Well, first of all, it’s a fundamental principle of copyright law that copyright can only protect the particular expression of an idea, not the idea itself. So no matter how original or innovative Parrott’s idea to feature emoji in various skin tones may have been in 2013, that underlying concept isn’t protectable. This means that CCI will only be able to succeed on its copyright infringement claim if it can prove that Apple’s emoji are substantially similar to the particular expressive elements contained in CCI’s racially diverse emoji.

But there’s another fundamental principle of copyright law that also comes into play here, and that’s the concept of “thin” copyright protection. Sometimes, there are only a limited number of ways to depict a particular subject matter. Consider a plant, an animal or another object naturally occurring in nature. If an artist wants to depict a realistic likeness of a Manx cat (as opposed to a dopey version of a Manx cat), there are only so many different ways to do that. In these types of situations, even if a particular expressive work is copyrightable, a court will only find infringement if the defendant’s version is “virtually identical” to the plaintiff’s work.

Some examples of works that courts have found are only entitled to “thin” copyright protection include a glass-in-glass jellyfish sculpture and a photograph of a vodka bottle. In these cases, the court held that the copyright owner was entitled to prevent others from copying any original expressive features of its copyrighted work, but was not permitted to preclude others from copying elements that flowed naturally from the type of work depicted. As a result, the owners of copyrights in so-called “naturally occurring” works only have a thin copyright that protects, at most, against “virtual identical” copying.

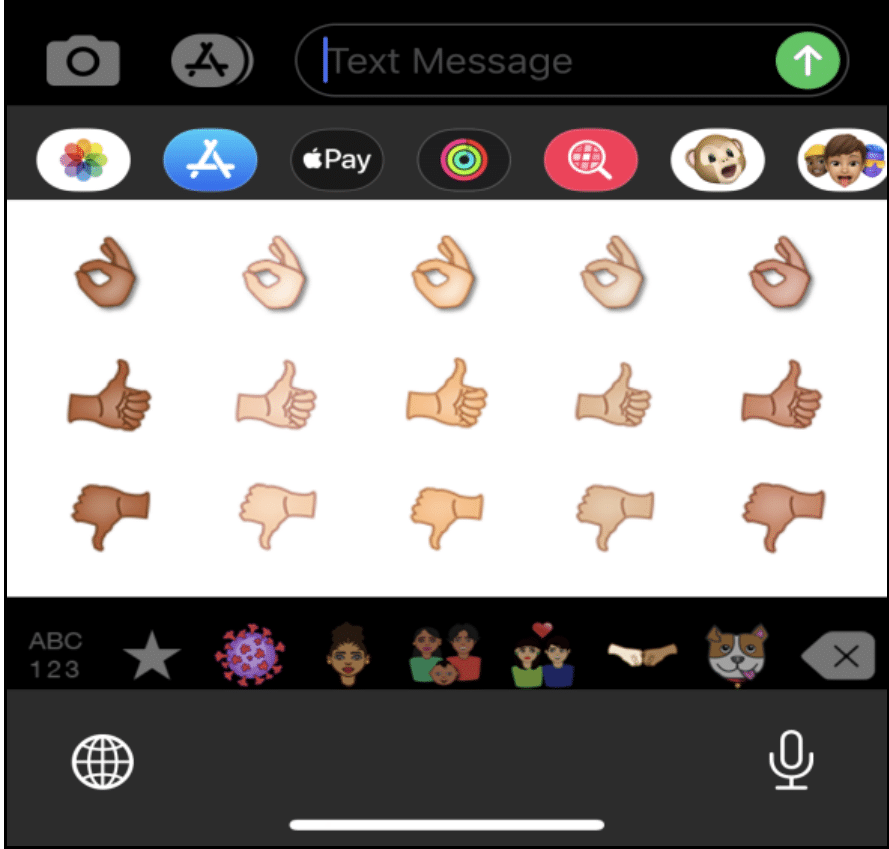

Against this backdrop, CCI is going to have a tough case against Apple. There are only so many ways that one can depict the image of an closed fist with a thumb extended upward, assuming that you don’t want it to look like this:

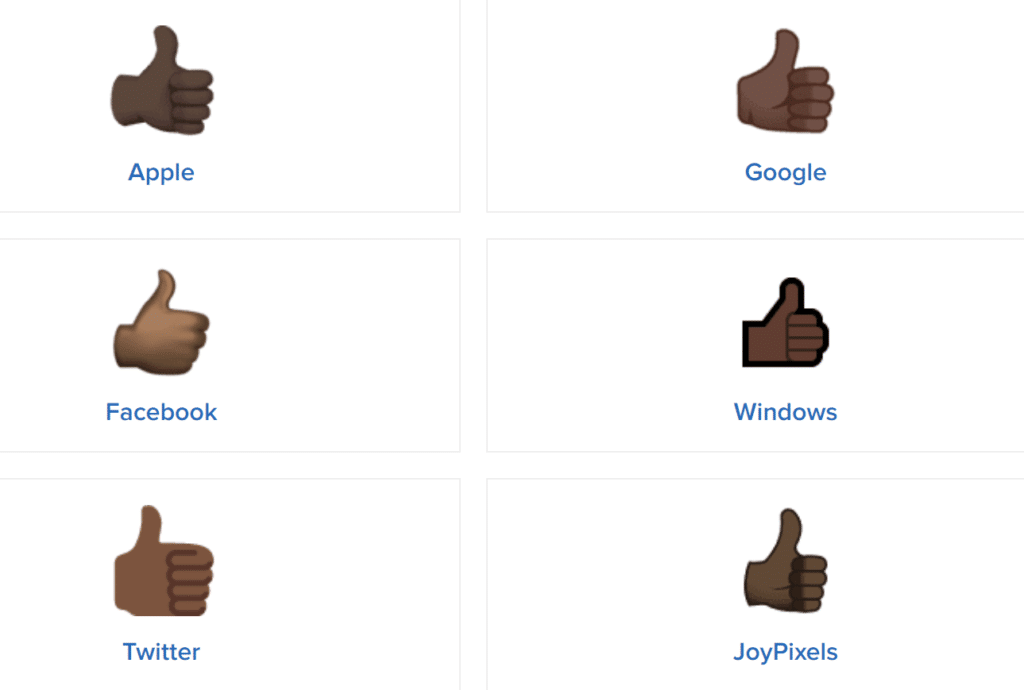

Here’s how a dark skin tone thumbs up emoji looks on different platforms:

And here’s the plaintiff’s dark skin tone thumbs up emoji compared to Apple’s:

Remember, we can only take into account the expressive elements of the images that don’t necessarily flow from the idea of a realistic looking thumbs up sign. In other words, the fact that there are four fingers, a clenched fist, and a thumb pointing upward on each one can’t be included in the similarity analysis. Taking into account Apple’s range of options, the emoji don’t look particularly similar. If anything, the plaintiff’s thumbs up design is more realistic than Apple’s. Apple’s thumb sort of looks like something you’d find on Fred Flintstone after being hit with Bamm-Bamm’s club.

Trade Dress Claims

In addition to its copyright claim, CCI also asserts causes of action against Apple for trade dress infringement under the Lanham Act, common law unfair competition, misappropriation and unjust enrichment. I don’t think these claims are going anywhere either. The trade dress claim requires CCI to show “secondary meaning” in her emoji—i.e., that the public recognizes iDiversicons as identifying a particular source. Most people don’t look at emoji in this way. They aren’t like logos that call to mind a particular brand in the mind of consumers. The fact that different versions of these emoji are used by different operating systems and platforms also undercuts CCI’s argument that the public would identify any particular emoji as identifying CCI’s brand. In addition, Plaintiff’s emoji are dictated more by function than aesthetics, which likewise precludes trade dress protection. The other claims pretty much duplicate the trade dress claim, and are likely precluded for the same reason.

All in all, I don’t expect that this one will go very far. The bigger question is whether the court will write its dismissal order in emoji.

As always, please comment down below or on your favorite social media platform @copyrightlately.