1. Ghostbusters, Part I

Back in 1984, Huey Lewis was a big star. In fact, he was so big that when the producers of Ghostbusters approached him about writing the theme for their upcoming film, Lewis had to decline because of previous commitments, including his work on the “Back to the Future” soundtrack. The Ghostbusters folks eventually settled on Ray Parker Jr. to write the film’s signature song. As the story goes, they provided him with a copy of a few scenes from Ghostbusters in which the theme would appear. Those scenes apparently contained the Huey Lewis and the News hit “I Want a New Drug” as temporary background music to show the kind of sound the producers wanted.

Parker’s “Ghostbusters” became a massive hit in its own right, reaching number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in August 1984. But Lewis thought the song was a rip-off of “I Want a New Drug” and made a copyright infringement claim against Columbia Pictures. The studio settled quietly out of court, so there’s no reported decision in this one. However, because both of these songs are still iconic 80’s staples, you can compare them below. (If you’re feeling adventurous, you can also take a listen to M’s “Pop Musik” from 1979, which didn’t spawn any legal claims.)

2. The Ghost of Mark Twain

In 1917, author Mark Twain had already been dead for seven years, but that didn’t stop him from writing a new book—allegedly. Twain’s spirit was said to have dictated the novel “Jap Herron” via Ouija board to journalist Emily Grant Hutchings, who transcribed his words through a medium.

Concerned about the effect the book would have on Twain’s reputation, publisher Harper & Brothers and Twain’s daughter Clara Clemens filed a lawsuit to stop further publication of “Jap Herron.” They argued that had Twain really written the book, Clemens’ estate would own the copyright and Harper would have the exclusive right under contract to publish it.

Faced with the prospect of either pulling Twain’s name from a poorly-reviewed novel that couldn’t stand on its own or turning over the book’s profits, publisher Mitchell Kennerley agreed to cease publication and destroy all remaining copies. Hutchings, however, never retracted her claim that the book was dictated to her from beyond the grave. You can judge for yourself by downloading a copy of “Jap Herron” here. One of the few remaining originals will set you back at least $400 on eBay.

3. A Nightmare on My Street

Readers younger than 30 hopefully know that before Will Smith became best known for slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars, he was the Fresh Prince half of the West Philly hip-hop duo DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince. Their iconic 1988 album “He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper” yielded the hit singles “Parents Just Don’t Understand” and the comedy-horror themed “A Nightmare on My Street.” The latter was originally considered for inclusion in the fourth Nightmare on Elm Street film, but the producers ultimately decided not to use it.

When record label BMG attempted to release a video for the song, film producer New Line filed a lawsuit for copyright infringement. Like the New Line films, the “Nightmare on My Street” video featured a villain named Freddy with a burnt face, a raspy voice and gloved hands with sharp instruments protruding from the fingers.

New Line successfully moved for a preliminary injunction to block the video’s release. The judge rejected BMG’s fair use defense, holding that the defendants took more elements from the Nightmare on Elm Street films than they needed to accomplish any parodic purpose.

Meanwhile, the video, once thought lost, is now on YouTube after more than a 30 year absence. Check it below and see what you think. Note the disclaimers at the beginning and end, which apparently weren’t enough to satisfy New Line. The case is New Line Cinema v. BMG (1988).

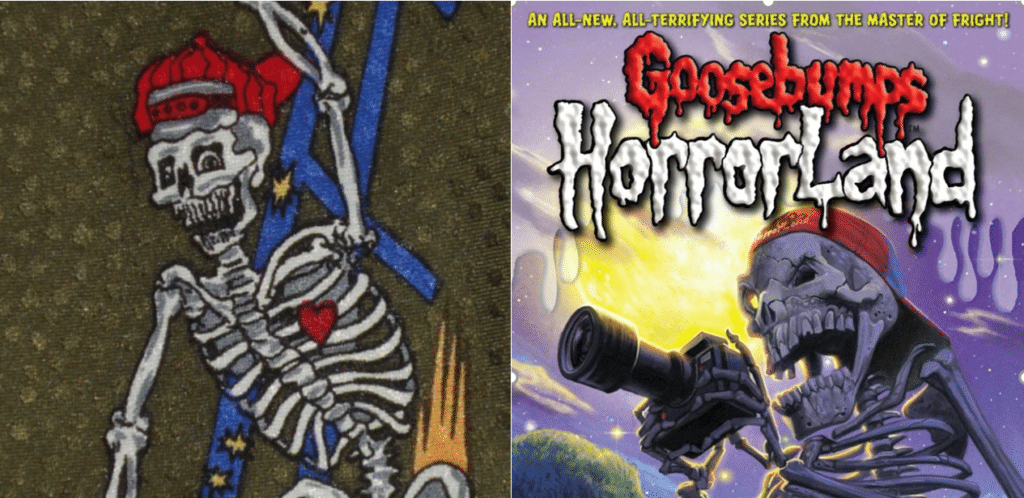

4. A Tale of Two Skeletons

The humanized skeleton figure on the left is Skully, which artist and entrepreneur Gregory Spiers first conceived while designing a T-shirt for the Lithuanian Olympic basketball team. The humanized skeleton figure on the right is Curly, a character designed for Scholastic’s popular “Goosebumps” series of books.

Spiers alleged that several images of Curly infringed his copyright in images of Skully, but the court in Scholastic v. Speirs found strong evidence that Scholastic had created Curly independently. Granting summary judgment for Scholastic, the court also noted that any similarities between the characters were primarily in unprotectable elements: the idea of a humanized skeleton and stock elements of a teen-age boy, including high-top sneakers, baggy shorts and a backward baseball cap. These are apparently go-to accessories for people who don’t have skin.

5. Dawn of the Dead

Long before “The Walking Dead” came on the scene, we had George Romero’s 1978 cult zombie classic Dawn of the Dead. In 2004, video game publisher Capcom contacted MKR, the film’s producer, to inquire about obtaining a license to use elements from the film in one of its games. Ultimately, Capcom decided not to pursue the license and instead placed the following disclaimer on the box for Dead Rising: “THIS GAME WAS NOT DEVELOPED, APPROVED OR LICENSED BY THE OWNERS OR CREATORS OF GEORGE A. ROMERO’S DAWN OF THE DEAD.™” The disclaimer didn’t satisfy MKR, which filed a lawsuit against Capcom, alleging that the game infringed its copyright and trademark rights in the film.

The court threw out the case on Capcom’s motion to dismiss. It found no similarity between Dead Rising and any protectable element of Dawn of the Dead. The few similarities acknowledged by the court were “driven by the wholly unprotectable concept of humans battling zombies in a mall during a zombie outbreak.” You know, typical Black Friday stuff.

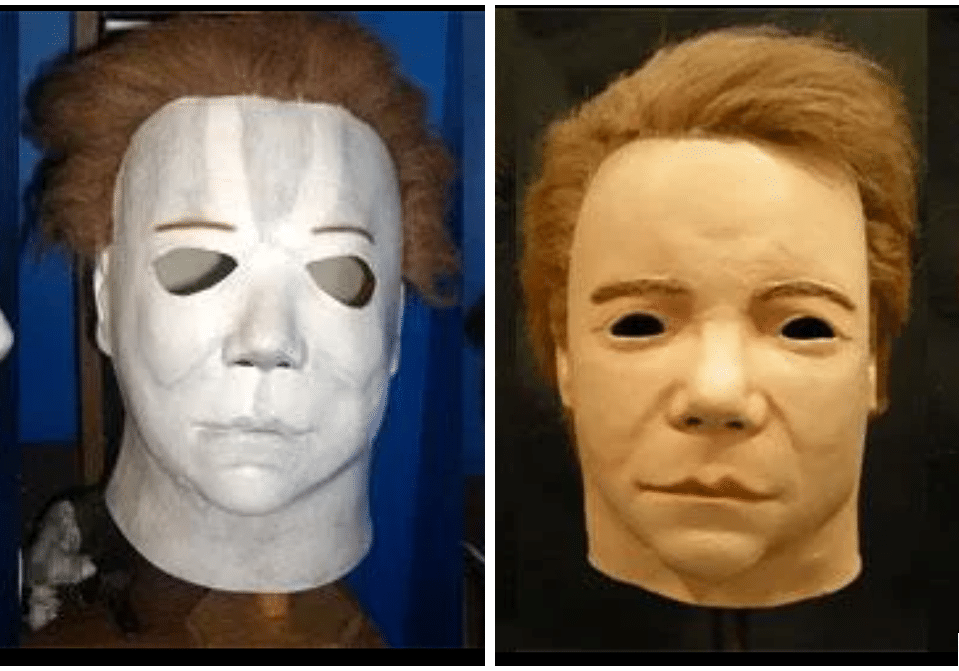

6. Halloween Mask

Many moviegoers have been frightened out of their wits by the sight of deranged serial killer Michael Myers from the 1978 classic Halloween. Perhaps they wouldn’t be so scared if they knew that the mask worn by the character in the film was actually a mold of actor William Shatner’s head. On second thought, maybe that would scare them more.

This bit of trivia, which had been the stuff of urban legends for years, was confirmed in the court’s opinion in Don Post Studios v. Cinema Secrets (2000). The film’s representatives asked effects artist Don Post to create a mask for their lead character by modifying a mask of Captain Kirk from Star Trek, which Don Post Studios had originally created from a mold taken of Shatner’s head. After “Halloween” became a hit, Don Post Studios began selling “Don Post the Mask,” a nearly identical mask that was also based on the Shatner mold.

In 1999, Cinema Secrets licensed the right to sell a Michael Myers Halloween mask from the film’s copyright owner. This prompted a lawsuit by Don Post Studios, which asserted that the Cinema Secrets mask was a copy of its own mask.

The claim failed, with the court finding that Don Post Studios didn’t have a valid copyright in “Don Post the Mask.” In a decision that surely disappointed Shatner, a mold of the actor’s head just didn’t have enough originality to qualify for copyright protection.

7. A Cabin in the Woods

In 2007, Peter Gallagher (an author, not the dad on The O.C.) wrote a book called “The Little White Trip: A Night in the Pines,” which he later alleged was infringed by the Joss Whedon-penned horror film The Cabin in the Woods.

The court found that while both works shared the same basic plot premise—a group of students venture off to a cabin in the wilderness and are subsequently murdered—this was a common and unprotectable horror staple. Beyond that, the overall stories were quite different.

Interestingly, Gallagher argued that the producers of the Cabin film had access to his book because he sold it on the Venice Beach boardwalk, at the Santa Monica Third Street Promenade and outside the Chinese Theatres. That was ultimately irrelevant to the court in the absence of sufficient similarities between the works, and the judge tossed the case.

8. Dracula vs. Nosferatu

We’re going way back in time for the next entry in the list, which involves Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula and the 1922 German movie Nosferatu. Stoker’s widow, Florence Balcombe, considered the film to be a pirated version of her husband’s book, and filed a lawsuit in Germany against producer Prana-Film to stop its distribution.

Following Prana-Film’s bankruptcy and several appeals, the court ordered copies of Nosferatu to be destroyed, sending agents to hunt down illegal copies. Film collector Henri Langlois, who had one of the few remaining copies of Nosferatu, ultimately saved the film from fading into oblivion. Eventually, Balcombe sold film rights in Dracula to Universal, which released the famous Bela Lugosi adaptation in 1931.

9. Conjuring up a Copyright Case

In 2016, author Gerald Brittle alleged that the Warner Bros. movie The Conjuring and its sequels infringed the copyright in his book “The Demonologist” as well as his claimed exclusive rights in the case files of paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren. These files were also the basis of the films, but Warner defended by pointing out that Brittle had asserted for years that his book contained a true account of historical facts, which aren’t subject to copyright protection.

The lawsuit, Brittle v. Warner Bros. (2017), raised an interesting example of “copyright estoppel” or, as the Ninth Circuit called it in the “Jersey Boys” lawsuit, the “Asserted Truths Doctrine.” By representing that a work is factual in nature, an author is prevented from later claiming that the work is fictional (and therefore protected by copyright). During the lawsuit, Brittle tried to shift the burden to Warner to prove that ghosts actually exist in order to defeat his claim, but unfortunately the case settled before any apparitions were called to the stand.

10. Termination Horror

Any list of 13 Halloween-themed copyright disputes needs to include 1980’s slasher film “Friday the 13th.” The film was the subject of a lawsuit between Horror, Inc., a company associated with the film’s producer, and one of the film’s screenwriters, Victor Miller. Miller sought to recapture rights in the original script via the Copyright Act’s termination provision.

Horror argued that Miller’s screenplay was produced as a work made for hire, which would make it ineligible for copyright termination. But last year, the Second Circuit disagreed, and said that Miller’s termination was valid. There may be some interesting issues going forward regarding the extent to which the infamous “Jason” (making only a brief appearance in the first film as child, sans hockey mask) is the same character as the machete-carrying adult that terrorized everybody in the numerous subsequent sequels.

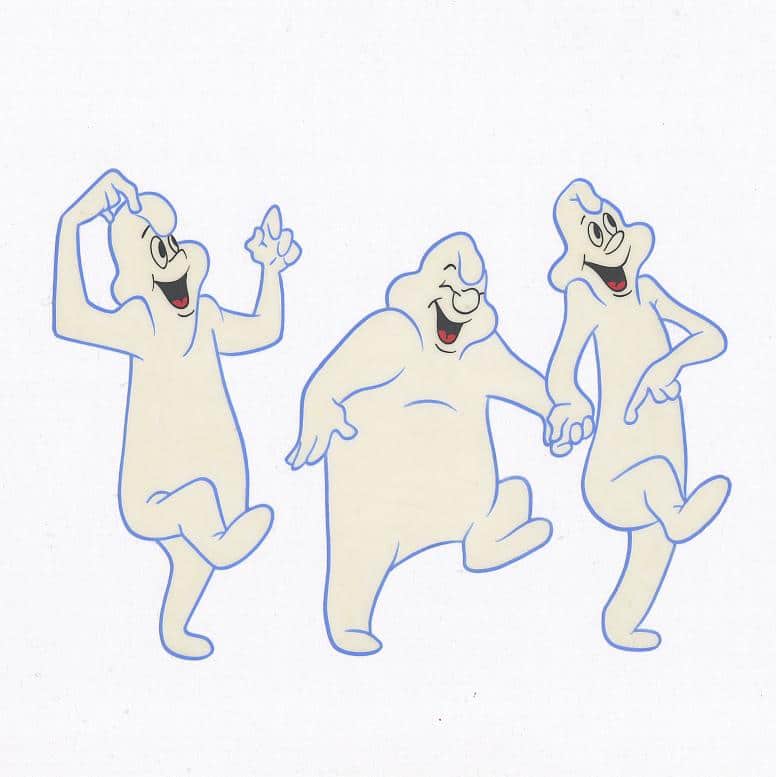

11. Ghostbusters, Part II

As if being accused of copyright infringement by Huey Lewis weren’t bad enough, Columbia Pictures also defended a copyright lawsuit from Harvey Comics in connection its Ghostbusters film. Harvey is perhaps best known for its “Casper the Friendly Ghost” character. If you’ve read the old comics, you know that Casper had three uncles, Lazo, Fusso and Fatso, who collectively comprised the “Ghostly Trio.”

Harvey claimed that the unnamed ghost in Columbia’s Ghostbusters logo infringed the copyright in Fatso, he of the knotted forehead and jowly cheeks. But the district court granted summary judgment in Columbia’s favor. It found that because Harvey had not renewed the copyrights on the comics featuring the character that later developed into Fatso, the depictions of the character relied on by Harvey had fallen into the public domain.

Harvey wasn’t saved by the fact that later issues of Casper remained subject to copyright. In a ruling reminiscent of a case I’ve previously discussed involving “Sherlock Holmes,” the court held that any copyrights Harvey still held in its later derivative works couldn’t be used to enlarge the scope of protection for works already in the public domain. While not the primary basis of the court’s ruling, the judge also noted that the similarities between Fatso and the Ghostbusters logo appeared to be ″stock features of cartoon ghosts in general.″ In other words, pudgy ghosts with knotted heads are no more protectable than William Shatner’s head. You can check out the summary judgment ruling in Harvey Cartoons v. Columbia Pictures (1986) here.

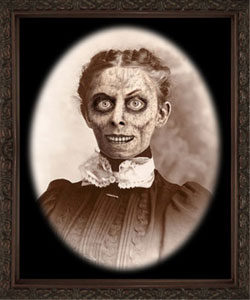

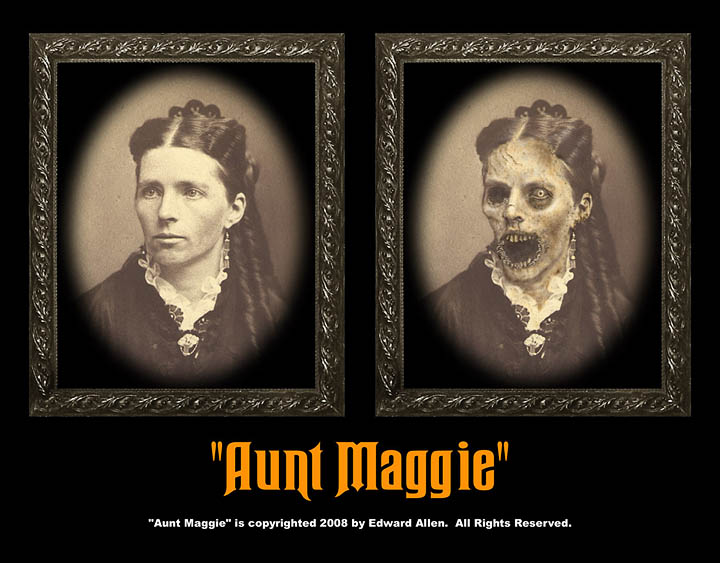

12. A Ghoulish Gallery

This case involved a fierce dispute between two competitors in the niche industry of spooky “changing portraits.” Plaintiff Edward Allen and Defendant Tim Turner both used lenticular technology to make antique-looking portraits appear to change into haunted spirits, vampires or other characters when the viewer shifts position slightly. The parties’ copyright battle arose when Allen claimed that Turner’s website, The Ghoulish Gallery, infringed on the website for his business, Haunted Memories Changing Portraits.

The court held that Allen had a valid copyright in the overall selection and arrangement of his website, but that copyright didn’t protect individual elements that were common in the horror genre, such as the use of a Ruben font, a “spooky eyeball” pattern in the background or placing the changing portraits in a gallery setting. Following trial, the court found that the similarities between the parties’ websites weren’t substantial enough to constitute copyright infringement.

13. The Man in the Moon

Back in the mid-1980s, ad agency Davis, Johnson, Mogul & Colombatto (DJMC) needed to solve a problem for its client, a group of Southern California McDonalds franchisees. The franchisees’ restaurant sales had stalled during dinnertime hours, and DJMC’s solution was “Mac Tonight.” He was a hipster crooner with a 3D crescent moon over his head who sang about getting dinner at McDonalds to the tune of “Mack the Knife.” The song was catchy, but the character used to give me the creeps.

Another person who wasn’t a fan of Mac Tonight was Nobert Pasillas, who in 1982 created a latex Halloween mask depicting the man in the moon. Pasillas’ mask featured a face on a concave surface, with eye holes matching up with the wearer’s eyes. The face on the mask depicted an elderly man with wrinkles, a bulbous nose, a rounded chin, and a closed mouth with slightly pursed lips.

For reasons unknown, Pasillas took a copyright lawsuit about this single mask all the way up to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which in Pasillas v. McDonald’s Corp. affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment for the advertisers. Comparing the two masks, the court found that while both were three-dimensional white crescent moons with a face on a concave surface, the differences stopped there.

Unlike Pasillas’s wrinkled face, Mac Tonight’s “youthful, unwrinkled face is defined by a pair of sunglasses, a triangular nose, no chin, thin lips and a broadly grinning, open mouth revealing the upper teeth.” Interestingly, the wearer sees out of the mask’s mouth, not the eye holes. Bottom line is that the masks were equally freaky, but not substantially similar as a matter of copyright law.

And there you have it! The 13 spookiest, Halloweeniest copyright cases that I could think of. Did I miss one that you think should have been included? Let me know in the comments below or on your favorite social media platform @copyrightlately. Happy Halloween!