In a 91-page report and recommendation, a magistrate judge finds that the new version of the Philadelphia Phillies’ mascot falls within the “derivative works exception” to copyright termination. But questions still remain.

Last year, I wrote about an epic copyright lawsuit between the Philadelphia Phillies and the original creators of the Phillie Phanatic over ownership rights in the beloved baseball mascot. Faced with the prospect of losing rights in the Phanatic, the team created a new version of its longtime mascot before the start of the 2020 season—angering many longtime fans in the process. Now, after nearly another full baseball season’s worth of legal wrangling, Southern District of New York Magistrate Judge Sarah Netburn today issued a 91 page report and recommendation on the parties’ cross-motions for summary judgment.

Overall, the report is a bit of a mixed bag for the team. While the judge rejected a number of arguments advanced by the Phillies (including arguments that the defendant committed fraud on the Copyright Office with its initial copyright registration), she ultimately recommended that the Phillies be allowed to continue using the new version of the mascot. However, the judge stopped short of approving a variety of additional designs featuring the Phanatic character, and left the team’s ability to merchandise the new version of the mascot unresolved for now.

Victor Marrero, the District Judge assigned to the case, will issue a final decision on the fate of Phanatic 2.0 after reviewing the magistrate’s report and recommendations, along with any objections filed by the parties.

The Judge’s Recommendations and the “Derivative Works Exception”

The Phanatic mascot costume was first designed in 1978 by Harrison/Erickson Inc. (H/E), a creative design firm, which in 1984 assigned the copyright in the mascot for a term of “forever.” Regular readers of Copyright Lately know that when it comes to United States copyright law, “forever” doesn’t actually mean forever, thanks to section 203 of the Copyright Act. That’s a law that allows authors and their heirs to terminate copyright assignments and licenses after 35 years, thereby recapturing the assigned rights “notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.”

However, section 203 is subject to an important exception. The law permits the owner of a derivative work prepared before termination to continue using that new work even after termination. Because the Phillies created its new mascot costume before the effective date of termination, the team argued that H/E’s termination notice wouldn’t prevent it from using the new version going forward.

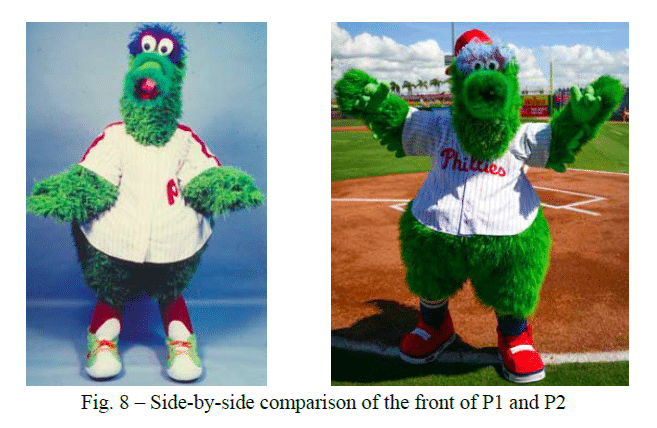

While the court described the derivative work issue as “the heart of this case,” the discussion of the derivative works exception doesn’t begin until page 57 of the magistrate’s report. H/E’s primary argument was that the new changes to the Phillie Phanatic (which include, among other things, powder blue eyebrows, a wider head and shorter snout than the original) were merely trivial variations, and therefore didn’t qualify as derivative works in the first place.

The court rejected H/E’s assertion (as well as those of its expert witnesses) that the new mascot costume was a “slavish copy” that wasn’t original enough to qualify as a derivative work. “To be sure, the changes to the structural shape of the Phanatic are no great strokes of brilliance,” but the court nevertheless found that the new work retained the same aesthetic appeal as the original, while featuring changes that were substantial enough to qualify as derivative works.

The Phillies had argued that the team was also entitled, under the Derivative Works Exception, to continue utilizing nearly 400 additional works featuring the new Phanatic, including designs for items of merchandise. However, the court found that as to these items, the parties had not adequately conducted a derivative works analysis and “the Court should not have to do this heavy lift for them.” If the magistrate’s judge’s recommendation is adopted, the parties would have to go to trial (or else settle out of court) to determine the extent to which the Phillies may use the new Phanatic beyond the mascot costume itself.

The Phillies case could have an impact far beyond the world of sports mascots, potentially serving as a blueprint for motion picture studios looking to ways to retain rights in fictional characters.

What’s Next + Implications of the Case

The parties have two weeks to file written objections to Magistrate Judge’s Blackburn’s ruling, at which time District Judge Marrero will decide whether to adopt her recommendations.

If he does, the Phillies case could have an impact far beyond the world of sports mascots, potentially serving as a blueprint for motion picture studios looking to ways to retain rights in fictional characters. So long as relatively modest changes are made to a character before copyright termination is effected, that derivative version could be used even after termination. And if the modified version has become the definitive representation of the character in the eyes of the public, this could significantly devalue the original grantor’s termination rights.

That said, there are reasons for the parties to discuss settlement. Putting aside that a number of issues will likely remain unresolved pending an expensive trial, the fact is that a large segment of the Phillies’ fan base doesn’t particularly like the “new and improved” version of the Phillie Phanatic. In light of H/E’s copyright termination notice (which the judge found to be valid), a settlement would be the only way to bring the original Phanatic back to Citizens Bank Park.

The true copyright nerds among us can read up on the remainder of the court’s recommendations below, which include a rejection of various arguments advanced by the Phillies to invalidate H/E’s original copyright registration and a discussion of whether the initial version of the mascot was a work of joint authorship. As always, if you have any comments, feel free to drop me a line below or on your favorite social media platform @copyrightlately.

View Fullscreen