The First Circuit rules that the classic 1960 board game “The Game of Life” was created as a work made for hire. Here’s why it matters.

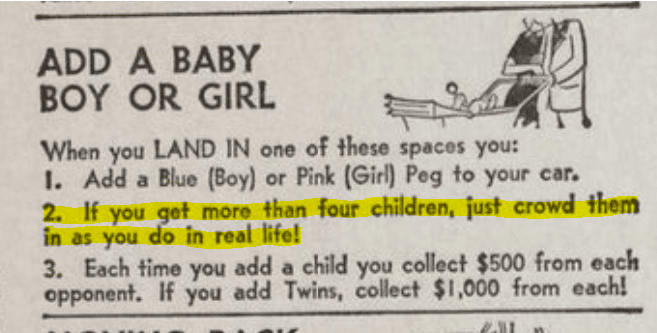

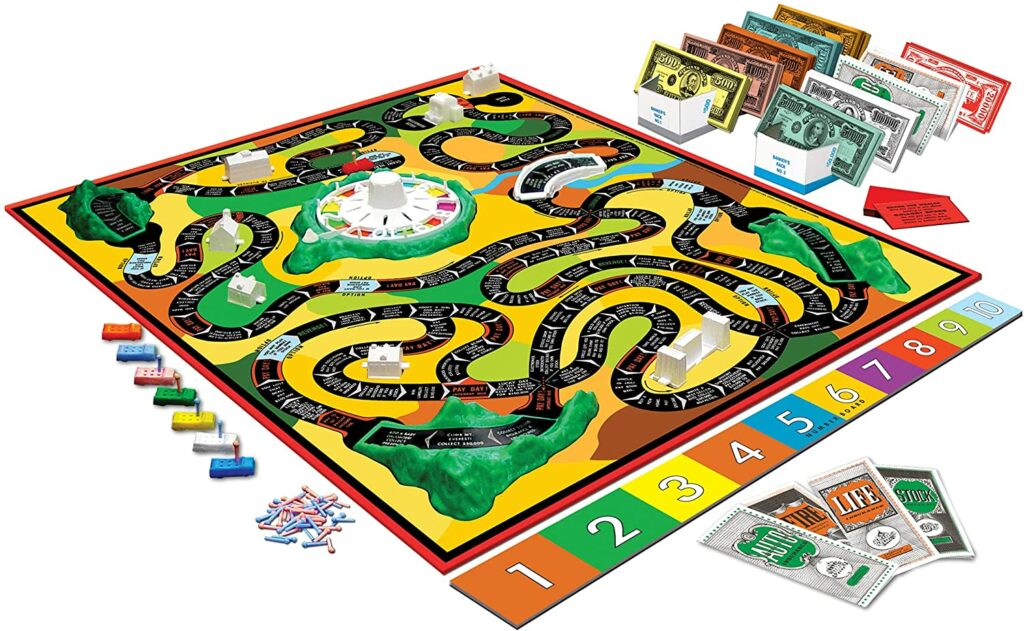

If you’ve ever played “The Game of Life,” you know there are lots of important decisions to make on your way to Millionaire Acres. Do you take the career or college path? Do you buy the overpriced home insurance that costs nearly as much as the house itself? Do you have more than four kids, even if it means taping some of them to the side of your car?

But it turns out that none of these decisions is quite as momentous to The Game of Life as the one recently faced by the First Circuit Court of Appeals, which prevents the heirs of one of the game’s original creators from recapturing rights in the work under the Copyright Act’s termination provisions.

Markham Concepts, Inc. v. Hasbro, Inc.

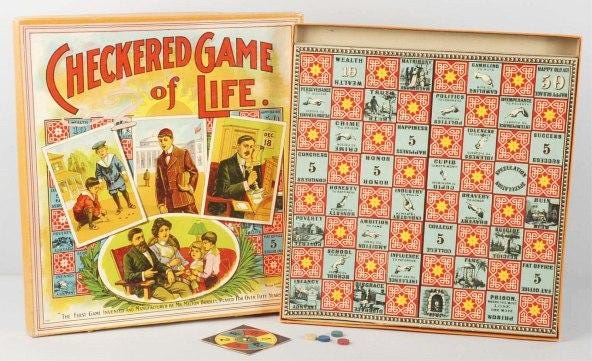

The decision, Markham Concepts v. Hasbro, affirms a 2019 ruling out of the District of Rhode Island, home of toy company Hasbro, Inc. Hasbro is the successor to Milton Bradley, which first published “The Checkered Game of Life” way back in 1860.

Nearly 100 years later, toy developer Reuben Klamer had the idea to update the game in commemoration of Milton Bradley’s 1960 centennial. But being more of an ideas person than a toy designer, Klamer needed assistance developing the concept and creating a working prototype that could be pitched to Milton Bradley. He hired Bill Markham, an experienced game designer and the head of a product development company, to help. Working closely with Klamer, Markham and two of his company’s artists built a prototype model featuring an elevated track, cardboard spinner and several of the game’s other signature elements.

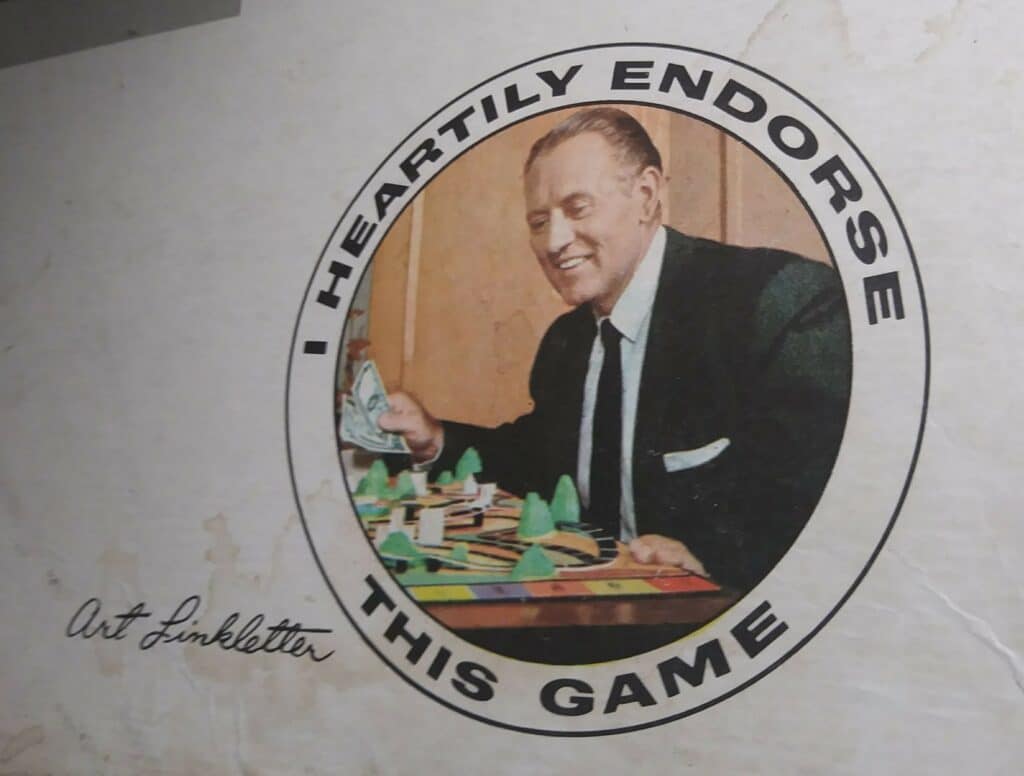

Once the prototype was finished, Klamer and Markham, accompanied by TV personality Ark Linkletter, met with executives at Milton Bradley to pitch the game. The toy company liked what it saw, and in 1959 entered into a license agreement with Klamer and Linkletter’s company, Link Research, to manufacture and sell the game in exchange for a 6 percent royalty. In turn, Markham assigned his rights in the game to Link in exchange for a 30 percent cut of Link’s royalties, plus an advance and reimbursement of the $2,400 Markham had spent on the prototype.

The game became a huge hit, and the rest is history—except that Bill Markham never got over the feeling that he’d gotten a raw deal.

In 2015, Markham’s heirs sued Klamer, the heirs of Art Linkletter and Hasbro, seeking a declaration of their right to terminate Klamer’s 1959 assignment under section 304 of the Copyright Act.

Copyright Termination and Works Made for Hire: Timing is Everything

I wrote in an earlier post about termination rights under Copyright Act section 203(a), which applies to copyright grants executed after January 1, 1978. Section 304 is similar, but it applies to works first copyrighted prior to 1978. Both statutes allow an author or his heirs to terminate prior transfers and recapture rights in a work for the remainder of the copyright term.

Both statutes are also subject to several caveats and exceptions. Most notably, termination rights don’t apply if a copyright was originally created as a work made for hire. In Markham’s case, both Klamer and Hasbro successfully argued that Markham’s contributions to The Game of Life constituted a work for hire, thereby preventing Markham’s heirs from terminating the rights.

The case highlights some critical differences between how “works made for hire” are defined depending upon when the copyrighted work at issue was created. Under the 1976 Act, there are only two ways for the work for hire doctrine to apply: the work either needs to be created by an employee within the course of his or her employment, or it needs to be a specially commissioned work falling within certain specified categories. In the latter case, the parties also need to expressly agree in a signed writing that the work is a “work made for hire.”

If “The Game of Life” had been developed any time starting in 1978, Markham’s heirs would have had a solid argument that the work for hire rules weren’t satisfied. There was no signed writing by which the parties agreed that it was a work for hire, and Markham wasn’t an employee of Klamer’s (although the contributions made by Markham’s own employees do muddy the waters a bit).

The “Instance and Expense” Test for Pre-1978 Works

The problem for Markham’s heirs was that at the time “Life” was created in 1960, a more liberal work for hire test applied, and it was relatively easy for any freelanced work to be considered a work for made hire authored by the commissioning party. Even now, courts apply the “instance and expense” test to these pre-1978 works. This test applies not only to traditional employment relationships, but also less traditional relationships, so long as the work was created at the hiring party’s “instance and expense” and so long as the hiring party had the right to “direct or supervise” the artist’s work.

In Markham’s case, the First Circuit had no trouble finding that the evidence supported the district court’s finding that The Game of Life was created at Klamer’s expense. Klamer promised to pay Markham for any costs incurred to create the game, regardless of whether Milton Bradley ultimately liked the prototype. And while Markham was paid a royalty as opposed to a fixed fee (which generally weighs against a work for hire relationship), the court found that the non-refundable advance distinguished this from a pure royalty deal.

The court also rejected the argument that Markham’s assignment agreement to Link Research rebutted the work for hire presumption, finding that the assignment was more of a “belt and suspenders” designed to ensure that Link was entitled to the copyright.

What’s Next?

Interestingly, the Second Circuit is currently considering another copyright termination case involving the classic horror film “Friday the 13th.” That case turns on whether the author of a post-1978 screenplay was an employee under the WGA’s collective bargaining agreement. Because the screenplay was written in 1979, section 203(a) and the 1976 Act apply to the termination issue. Had the script been written just two years earlier in 1977, the 1909 Act’s “instance and expense” test would have applied, and as in the “Life” case, the film would have easily been considered a work made for hire.

As they say, in Life (both the game and real versions), timing is everything. As always, drop me a comment and let me know your thoughts. Meanwhile, a copy of the First Circuit’s opinion is below.

View Fullscreen