Nirvana has been sued for using an illustration from a 1949 translation of Dante’s “Inferno” on band merchandise. Here’s why determining the copyright status of old foreign works can be a hellish undertaking.

Move over smiley face. Welcome to the Seventh Circle of Hell.

Nineties grunge-rock band Nirvana, already embroiled in a long-running legal battle against fashion company Marc Jacobs over its “happy face” t-shirt designs, now finds itself on the less happy end of a new copyright infringement lawsuit worthy of Dante’s trip through the underworld.

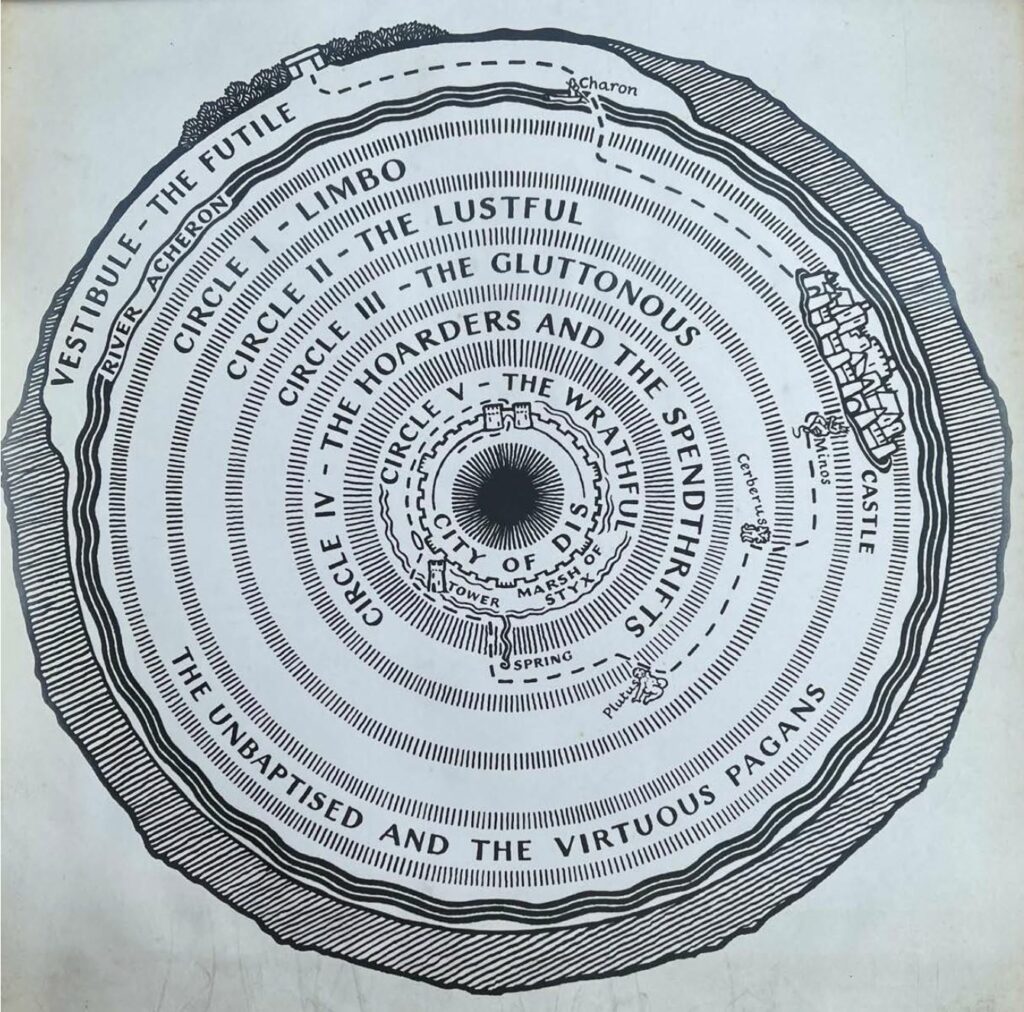

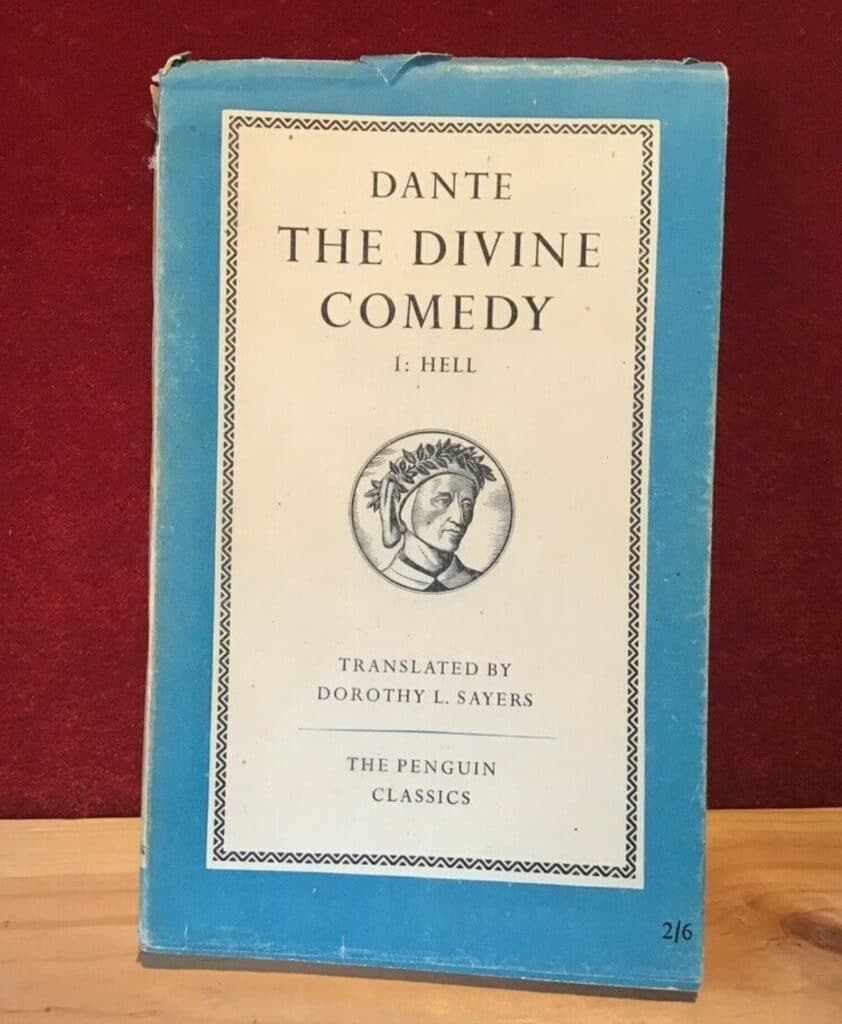

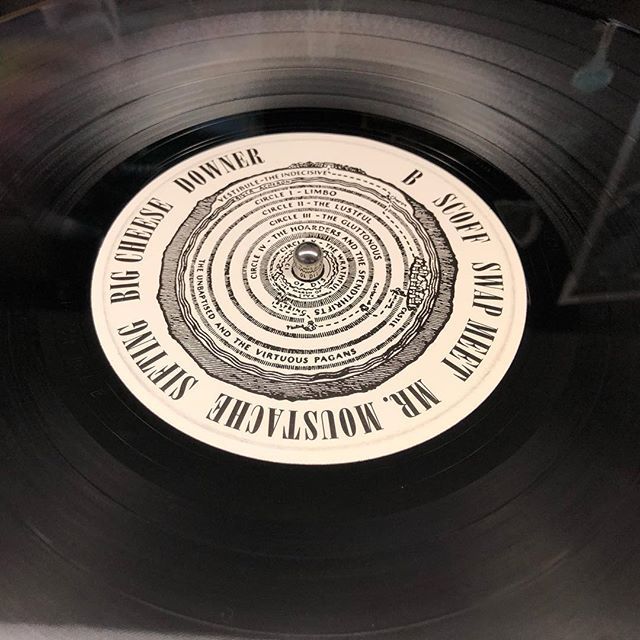

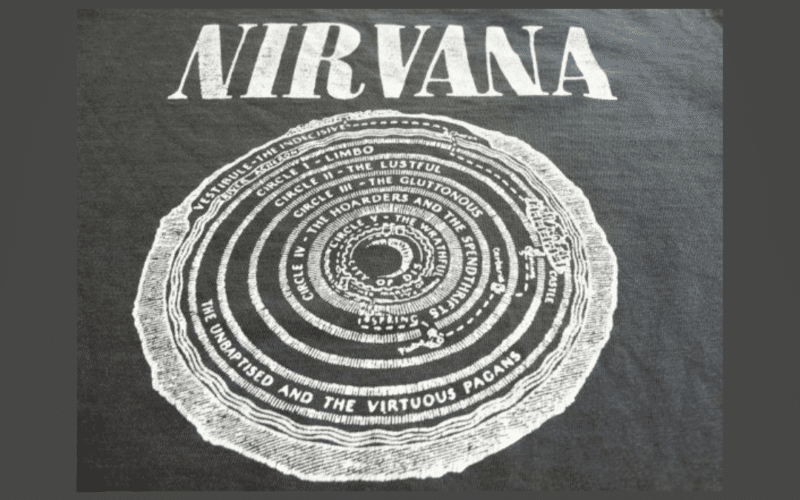

The complaint, filed in federal court in Los Angeles, claims that Nirvana infringed an illustration first published in a 1949 English language translation of Dante’s “Inferno.” The drawing depicts Dante’s circles of Upper Hell and, like Nirvana’s smiley face logo, has been featured on the band’s merchandise for decades.

The new lawsuit raises a host of complicated legal issues that, while exciting for copyright nerds like me, are often a nightmare to litigate. Key among them is the extent to which pre-1978 works first published abroad without proper copyright notice are still protected under U.S. copyright law. The fact pattern presented in the plaintiff’s complaint is pretty devilish, made possible by the draconian notice and registration requirements imposed by the 1909 Copyright Act.

Bundy v. Nirvana LLC

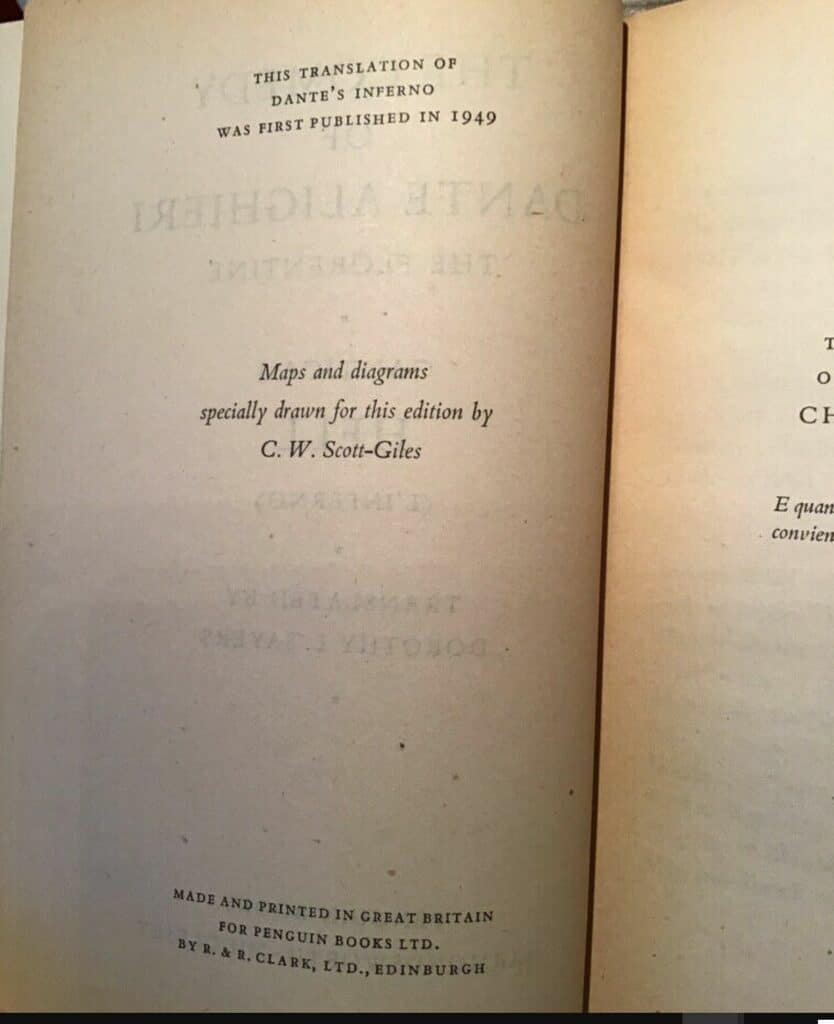

The plaintiff is Jocelyn Susan Bundy, a U.K. citizen who claims to be the sole surviving relative and successor-in-title to the copyright in the works created by her late grandfather C.W. Scott-Giles, who died in 1982. One of Scott-Giles’ works is a drawing of Upper Hell as described by Dante Alighieri in his literary trilogy “The Divine Comedy.” According to the complaint, Scott-Giles drew the illustration in 1949 to accompany an English translation of the first volume of the trilogy (“Hell” aka “Inferno”) by Dorothy L. Sayers.

The Sayers translation, which featured the Scott-Giles drawing at issue (entitled “Upper Hell”) was first published in the U.K. on November 16, 1949. The U.K. version of the book credited Scott-Giles for the maps and diagrams he specially drew for the edition, but didn’t contain a copyright notice.

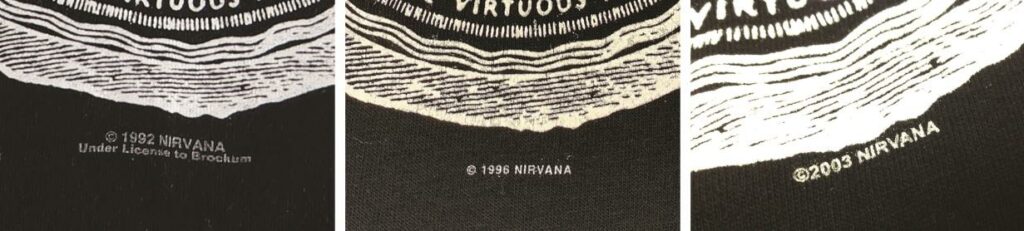

Bundy claims that it wasn’t until early 2021 that she first discovered that Nirvana, Live Nation Merchandise and others have been exploiting t-shirts, hoodies, mugs and similar merchandise featuring the “Upper Hell” illustration in both the U.S. and abroad for years. Some of these products have allegedly been sold as far back as 1989.

You may be asking where in the hell (sorry) this plaintiff has been for the past 30 years. It appears that Bundy only learned of Nirvana’s use of “Upper Hell” in connection with the Marc Jacobs “happy face” lawsuit and a related lawsuit by Nirvana against Robert Fisher. During the course of these proceedings, Nirvana band member Krist Novoselic and manager John Silva asserted that Nirvana’s “Happy Face” t-shirt was similar to another t-shirt allegedly created by Kurt Cobain, which Nirvana fans have come to know as the “Seven Circles of Hell” or “Vestibule” design.

Bundy’s complaint claims that Nirvana has “routinely made false claims of ownership” by placing copyright notices in its name on allegedly infringing merchandise featuring the illustration.

Despite these copyright notices, Nirvana is now taking the position that the “Upper Hell” illustration is in the public domain and therefore free to use. It argues that when the U.S. version of Dante’s “Inferno” was first published, the book included a copyright notice stating “Copyright 1949 by Dorothy L. Sayers.” However, it apparently wasn’t thereafter registered or renewed with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Bundy says none of that matters. As a work created by a British citizen and first published in the United Kingdom, she claims that the illustration is a “foreign work” for purposes of U.S. copyright law and that it still enjoys protection both here and abroad.

The Copyright Status of Foreign Works

The legal issue, simply stated, is whether a work first published in a foreign country without proper copyright notice is subject to copyright protection in the United States. The answer, unfortunately, isn’t so simple, at least for works first published before 1978. It’s made even more complicated as a result of a controversial Ninth Circuit case, Twin Books v. Walt Disney Co., which involved the novel “Bambi, a Life in the Woods,” first published in Germany in 1923 without copyright notice. (While you may not think Bambi would provoke controversy, the book was actually banned by Hitler in 1936 because of its “political allegory on the treatment of Jews in Europe.” As for the Disney film, let’s not forget that hunter scene.)

Under the 1909 Copyright Act, U.S. copyright was secured by foreigners complying with the requirements of U.S. law. Most commentators, including the Copyright Office, assumed that the failure to comply with U.S. formalities placed foreign works in the U.S. public domain (subject to potential restoration, which I’ll discuss shortly).

But in Twin Books, the often-contrarian Ninth Circuit concluded that “publication without a copyright notice in a foreign country did not put the work in the public domain in the United States,” essentially treating these works as if they were “unpublished.” So, at least within the western states covered by the Ninth Circuit, a foreign work published without notice would not only be spared from the public domain, but would now enjoy protection for the life of the author plus another 70 years. (For more, check out Cornell’s incredibly useful public domain chart, which is available via Copyright Lately’s “Resources” page.)

Relying on Twin Books, Bundy claims that her grandfather’s “Upper Hell” illustration never entered the public domain, and will be protected until 2052 (70 years from Scott-Giles’ death). But there’s a wrinkle. While the version of Sayers’ book published in the U.K. didn’t include any sort of copyright notice, the 1949 U.S. version did. And yet, it doesn’t appear that copyright registration or renewal was obtained in the book as required under the 1909 Act. Therefore, I expect Nirvana to take the position that even if the initial U.K. publication without notice wasn’t itself enough to inject the work into the public domain, the subsequent U.S. publication with notice but without registration prior to 1978 did just that.

Adding another layer of complexity is the fact that the copyright notice affixed to the 1949 U.S. publication was in the name of Dorothy Sayers, as the book’s translator, not Scott-Giles as the illustrator. This may yet give Bundy a hook to argue that the U.S. edition was published without notice as to Scott-Giles’ contributions, and that his “Upper Hell” illustration should still be treated as “unpublished” under Twin Books.

Do you have a headache yet?

If not, I’ll note that a number of subsidiary issues are also likely to arise in determining whether Bundy, as successor to Scott-Giles, is able to claim protection in her late grandfather’s work. For example, if Scott-Giles created the illustration as a work-for-hire on behalf of Dorothy Sayers (an issue that would need to be determined under the laws of the U.K.), Sayers or her publisher may have owned the illustration in the first instance.

The Copyright Restoration Act

As an alternative argument, Bundy contends that even if the “Upper Hell” illustration had previously fallen into the U.S. public domain, its copyright has since been automatically restored pursuant to the Copyright Restoration Act. The Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA), passed in 1994, amended the Copyright Act to restore U.S. copyright to certain foreign works that, while still protected by copyright in their source countries, fell into the U.S. public domain for failure to comply with the various formalities (such as notice, registration and renewal) formerly imposed under U.S. law.

There are a number of conditions that need to be satisfied to qualify for copyright restoration. At least one of the authors/rightsholders must be a national or domiciliary of an eligible source country. The work can’t be in the public domain in its source country through expiration of the term of protection, and it needs to be in the public domain in the U.S. for failure to comply with formalities. Finally—and probably most critical for Bundy’s case—the work must not have been published in the U.S. during the 30-day period following its first publication in the eligible country.

The final requirement is going to require the parties to go back and determine whether the U.S. version of Sayers’ book was published within 30 days after the date on which the book was first published in the U.K. Remember, the book is more than seventy years old, so this should be fun.

To make things just a tad more complicated, the URAA contains an exception for so-called “reliance parties”— parties who have acted in reliance on a particular work being in the public domain prior to 1996, when the Copyright Restoration Act took effect. Once a work is restored, a reliance party may continue to exploit the work without liability until there is proper notice of an intent to enforce, at which point the reliance party has one year to sell off its stock of copies.

Expect the parties in the Bundy case to fight about such things as whether Nirvana LLC is a proper successor to the band’s earlier exploitation of the “Upper Hell” illustration on various merchandise created prior to the LLC’s existence. There’s also the issue of the copyright notices in Nirvana’s name on some of this merchandise. These notices may call into question whether the band was actually relying on the public domain status of the illustration in exploiting the work, as opposed to holding itself out as the rightful owner.

Different Countries, Different Protection

As I noted in the section of my “Copyright Myth Project” dealing with public domain works, just because a work is in the public domain in the United States doesn’t mean it’s in the public domain everywhere. Each country has its own copyright laws, and if a work was first published outside of the U.S., it may still be protected in its “source country.”

Therefore, in addition to asserting a claim against Nirvana LLC (along with Live Nation Merchandise, Merch Traffic and Nirvana’s management company), Bundy is also asking the court to decide whether the defendants are liable for copyright infringement in the U.K. and Germany.

The U.S. Copyright Act doesn’t apply extraterritorially, which means that if the court decides to accept jurisdiction over these claims, it will need to apply foreign law—that of the United Kingdom and Germany respectively. While it’s pretty rare for courts to decide copyright claims under foreign law, it’s not unheard of, especially if there’s also a cognizable claim under U.S. law over which the court has jurisdiction.

Removal of Content Management Information

Finally, Bundy is asserting a separate claim against the defendants under Section 1202 of the Copyright Act, which prohibits the knowing falsification, removal or alteration of “content management information” (CMI) with the intent to conceal infringement. Often an issue in copyright cases involving photographs, CMI generally extends to such information as the author’s name and any copyright notices appearing on the work. Here, Bundy is arguing that Nirvana violated the law by removing both the title and Scott-Giles’ credit line from the “Upper Hell” illustration, often replacing it with copyright notices in the name of Nirvana itself.

Bundy v. Nirvana LLC would make for a pretty good final exam fact pattern if anyone out there is a copyright professor at the University of Hell Law School. I’m definitely interested in seeing how it all turns out, and would love to hear your thoughts as well. Drop me a comment below, or @copyrightlately. A full copy of the new complaint is below.

UPDATE—October 21, 2021—The Central District of California court has decided that the United Kingdom would be a more convenient forum than the United States to decide Bundy’s lawsuit against Nirvana. But contrary to some of the articles I’ve seen, the dismissal does not mean that Nirvana has “won” its case. And the dismissal comes with certain conditions. Nirvana must agree submit to UK jurisdiction, must agree to to use United States discovery procedures in the UK action and—perhaps most significantly—must agree to pay any judgment that may be ordered by a UK court. I’ll keep you posted on any new overseas developments!

2 comments

Excellent article tracing the outline of what promises to be a fascinating case. Could the consideration of choice of defence strategy here, versus impacts on the prior litigation Nirvana have been subject to, be added as an addendum? Or is that a red herring?

Thanks for reading! As I noted in my new update at the end of the post, unless the case settles, Nirvana will now likely be defending the lawsuit in the United Kingdom—which should make it easier for Nirvana to avoid attempts to introduce evidence from the “Happy Face” litigation that’s pending here in California. That’s not to say Bundy won’t try, but my sense is that a UK judge is more likely to focus on the case at hand.