In a new lawsuit, Clayton Haugen claims Activision infringed his photo copyrights by using the same model to create its “Modern Warfare” character. Does he have a case?

An interesting new copyright lawsuit was filed on Tuesday against Activision, publisher of the massively popular “Call of Duty” video game series.

Haugen v. Activision Publishing

The plaintiff is writer and photographer Clayton Haugen, whose works focus on “dystopian science fiction, post-apocalyptic, and military themes.” According to his complaint, Haugen created a female vigilante character named Cade Janus, which he featured in a futuristic story called “November Renaissance.”

In 2017, Haugen recruited a model to portray the Cade Janus character so he could present his story to film studios. Haugen’s photos were published on his web site, on Instagram and in a series of calendars.

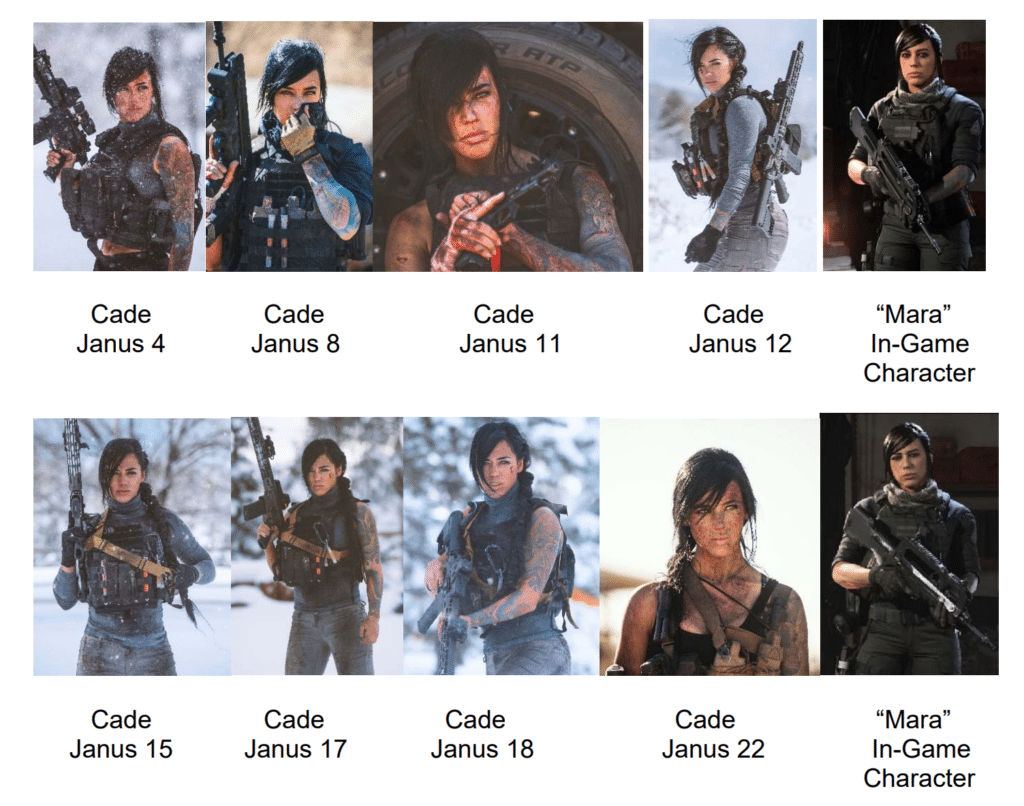

Haugen alleges that Activision “deliberately copied” his photographs by hiring the same model from the photos—wearing the same clothing and accessories—to develop the “Mara” character that appears in its video game “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.” The game’s developer Infinity Ward also allegedly hired the same makeup artist who prepared the talent for Haugen’s photos, and instructed her to style the model in the same way. Below are some of the side-by-side images included in Haugen’s complaint:

While she isn’t identified in the complaint, the model is Alex Zedra, who’s also a Twitch streamer. She also looks to be a pretty big fan of large weapons.

Huffman v. Activision Publishing

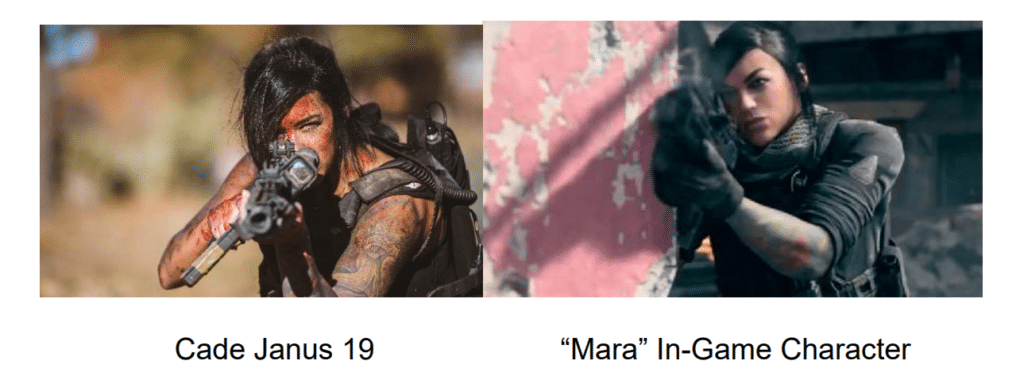

If you’re an astute observer of video game copyright cases, Haugen’s claims might sound a bit familiar. The fact pattern is similar to Huffman v. Activision, another case brought against the “Call of Duty” publisher in the same court by the same lawyer.

A summary judgment opinion in Huffman made my list of the “5 Worst Copyright Decisions of 2020” because the judge allowed the case to go to a jury trial with nary a discussion of whether the defendant’s work was substantially similar to any of the protectable elements contained in the plaintiff’s work. As I noted in my write-up on the case, the only real similarities between the two works were that they both featured military men with dreadlocks holding weapons in a standard military pose—which aren’t subject to copyright protection.

I think the same is true here. The fact of the matter is that any two photos of the same model wearing tactical gear are necessarily going to look similar. But those elements aren’t protected by copyright law.

While there have been a few cases which have held that photographer’s slavish recreation of a human model (or even a string of puppies) may give rise to a valid copyright claim, in those cases, the defendant’s copying extended to the same compositional elements, such as lighting, pose and camera angle.

Gross v. Seligman

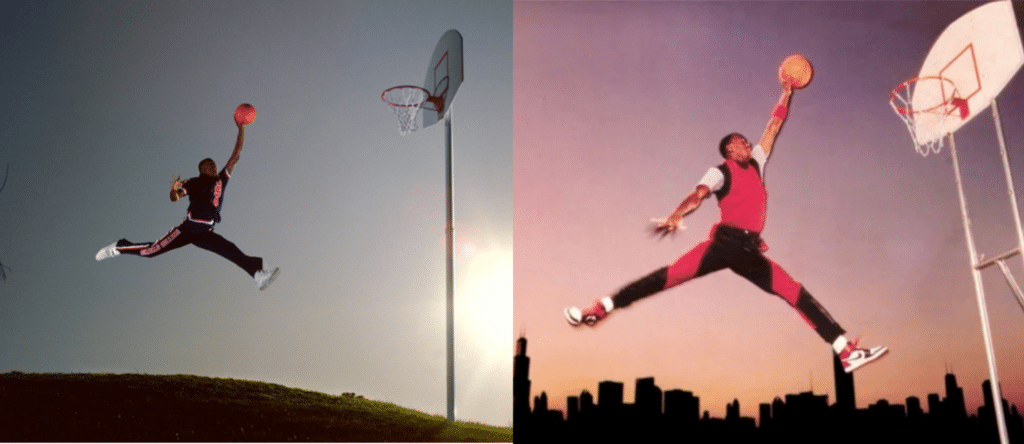

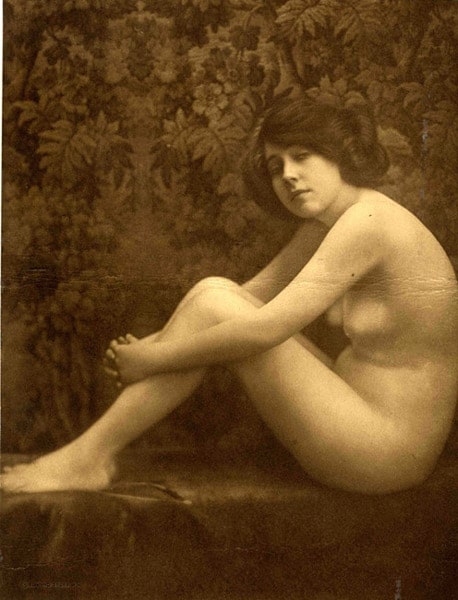

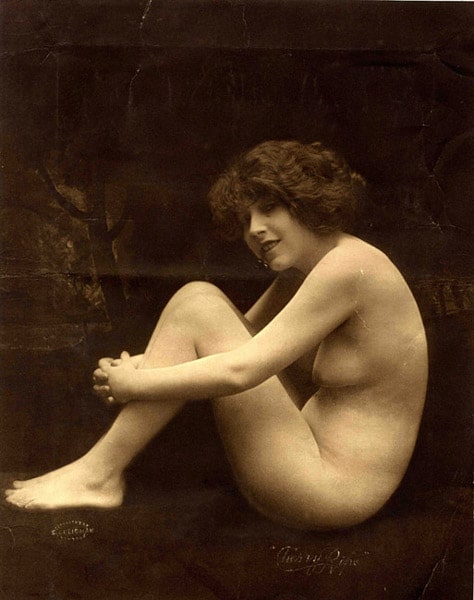

Way back in 1914 in Gross v. Seligman, an artist posed a nude model, whom he photographed for a piece called “Grace of Youth.” Two years after selling his rights in the photo to the plaintiff, the artist placed the same model in the identical pose except that in the second photograph the model was smiling and held a cherry stem between her teeth.

“Grace of Youth” “Cherry Ripe”

The court held that the second photo was a copy of the first, meaning that the artist had basically ripped himself off (an unfortunate distinction which would later be shared by John Fogerty).

Rentmeester v. Nike

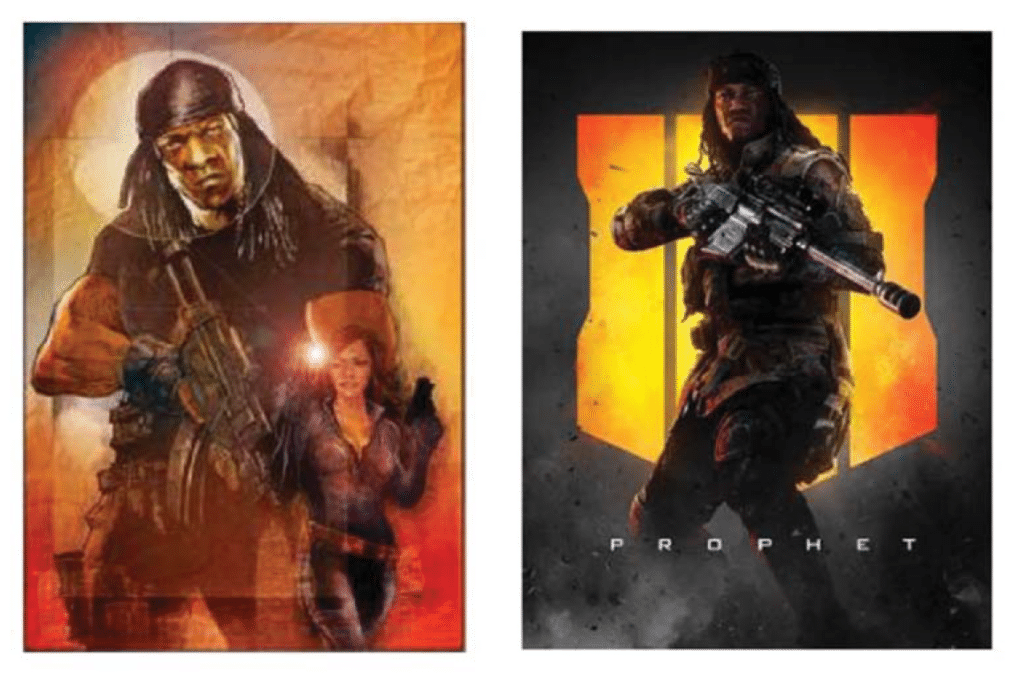

Frankly, the photos in Seligman really weren’t all that similar, and while the second was no doubt a “copy” of the first (as opposed to an independent creation), it’s doubtful that a court today would find copyright infringement. Copyright law doesn’t allow a photographer to monopolize any particular pose or photographic subject. While a photographer’s particular expression of a pose may be protected, the underlying idea for the pose isn’t. This concept was illustrated recently in by the Ninth Circuit in Rentmeester v. Nike.

Both of the photos at issue in the case feature Michael Jordan in his iconic “Jumpman” dunk pose, but Jordan’s pose is slightly different in each shot, as is the angle, background, and the lighting. The Ninth Circuit agreed that the case was properly dismissed at the pleading stage based on these differences.

Without a contractual restriction in place, Haugen couldn’t legally prevent his subject from also appearing in the Activision game. And if you remove all of of the similarities that flow from her likeness, there’s not much left.

I should note that Haugen also claims that Activision copied additional character elements for Mara from his “November Renaissance” story. Those allegations aren’t particularly well-developed, and the complaint really doesn’t even appear to allege that Activision had access to Haugen’s story. Normally, I would say that Haugen’s case isn’t long for this world, but the case is pending in the plaintiff-friendly Eastern District of Texas, so it’s anyone’s guess what happens next. Either way, I’ll keep you posted.

In the meantime, take a look at the full complaint below and let me know what you think.

View Fullscreen

2 comments

For scores of years, comic book and paperback artists have used existing images as reference. There are two reasons: either a look is ‘right’ for the assignment or the budget is insufficient to hire a model. Many artists clip images and keep them in so-called ‘swipe’ files.

In 1931, Boris Karloff played the Frankenstein Monster for Universal. Makeup artist Jack Pierce tested a look with forehead bolts which were subsequently discarded. Over thirty years later, renowned artist James Bama used that photograph as the basis for a paperback edition of Frankenstein. The same image was interpreted for a Famous Monsters of Filmland feature “Lon Chaney Shall Not Die,” speculating what the Monster would have looked like had the silent screen star lived to play the role.

As you note, examples abound. The argument can be made that such use is inherently transformative.

Thanks Jeff – here are links to the photos you referenced so others can see them:

https://copyrightlately.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Karloff.jpg

https://copyrightlately.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Chaney.jpg

https://copyrightlately.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Bama.jpg